She describes how her father, convinced finally of the reality of Labour’s landslide win, rose from his chair, grabbed the sheaf of doctor’s bills pinned to the wall and threw them into the fire.

A thrilling vignette, which captures perfectly the socially transformative power of electoral politics when done right — that is to say, when done by the working class.

You can imagine my disappointment then, when I read the following sentences from Rob Campbell, who, at one time, was a leader and defender of the working class: "In our welfare state developed in the middle of the last century, as part of the ‘quest for security’ there was strong emphasis on universal services and benefits. Though far from exclusive, this has continued to be a preferred approach from political parties on the left."

The first niggles of concern, raised by this opening brace of sentences in Campbell’s latest contribution to the Newsroom site, found crushing confirmation in what followed.

According to this erstwhile unionist: "This was substantively shattered over the last half-century by social changes driven by cultural and other identity expression, by regulatory, ownership, technology and economic structural shifts. This was a mix of progressive and regressive change which has created a whole new reality."

Ummm, no. The realities of being poor and working class have not changed. What has changed is the party that was once pledged to — and did — alter the realities so powerfully depicted by Janet Frame.

The "new reality" Campbell alludes to (but does not acknowledge) is that for the past 35 years, Labour has been the political vehicle not of the working class, but of the professional and managerial class (PMC).

What most defines this class is its close-to-obsessive preoccupation with supervision. The PMC has no interest in liberating the poor and oppressed. Its primary focus has been, and will always be, to oversee and guide (gently, or not so gently) the uncredentialed and the unconvinced.

It’s the PMC who say: "we’re from the government and we’re here to help", under the mistaken impression that those they’re addressing will find the information reassuring.

According to Campbell, the left’s "lazy" allegiance to the principle of universal entitlement "resurrects an old slogan and emotion but ignores current realities. Out there, among those left behind in the privatisation of our lives, there are any number of community activists and agencies both old and new. They are where the solutions are to be found".

But then, he would say that, wouldn’t he? Because community activism, undertaken in "agencies both old and new", be they ministries or trade unions (Campbell’s old stamping ground) or the scores of NGOs employing the recently graduated children of the advantageously credentialed and the ideologically convinced, is where the PMC’s supervisory rubber really meets the societal road.

Universal rights and entitlements are the very last promises that should be made when the actual challenge is how to manage the "social changes driven by cultural and other identity expression".

God forbid that membership of the human species should, once again, become the sole criteria for assisting "those left behind in the privatisation of our lives".

No, according to Campbell the most important lesson that centralising government agencies can learn from community-based organisations is that "one size does not fit all."

Acceptance of this key insight can only be delayed, he argues, if a lazy and nostalgic left insists upon "maintaining views that seek to reinstate past practices".

Among which would appear to be the practice of democracy. The word does not appear in Campbell’s Newsroom post.

This is hardly surprising, since nothing infuriates the PMC more than the votes of poorly educated people counting for exactly as much as the votes of highly educated people.

And yet, it was precisely this equivalence that empowered Janet Frame’s father to rise from his chair and destroy the medical bills he could not pay. It was the efficacy of the vote that he (and thousands of others like him) had cast, trusting in the promises of Labour activists drawn from the same working-class communities, that gave him the courage to consign his inequitable debts to the flames.

It’s the one thing for which we are all fitted, Rob — dignity.

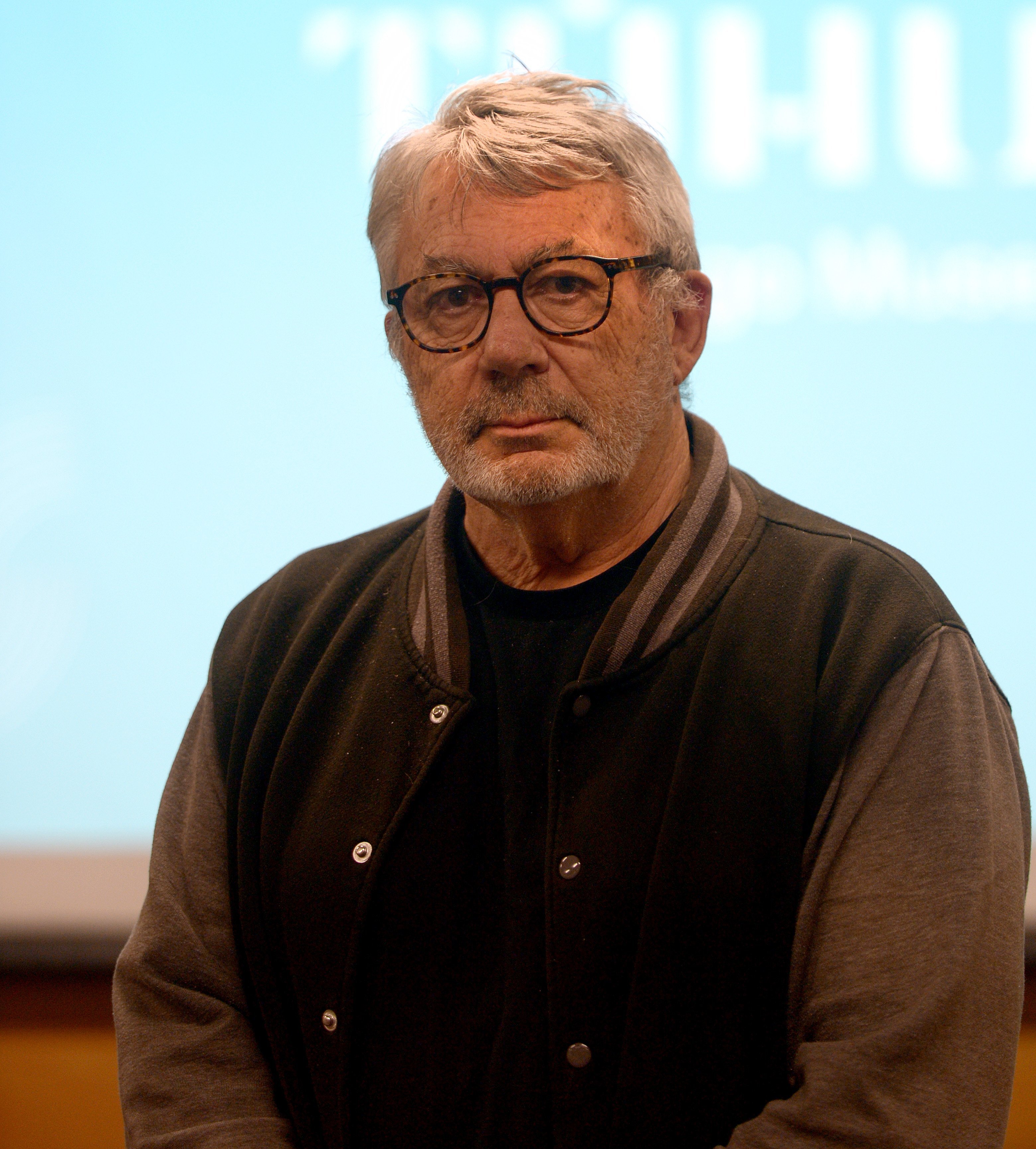

■Chris Trotter is an Auckland writer and commentator.