A new book on my shelf is called Birds of Aotearoa New Zealand: Collective Nouns. Its author, Melissa Boardman, combines lovely illustrations with clever collective nouns for our own special birds, such as "an ecstasy of tui" and "a raft of little blue penguins". The book made me wonder: what is the collective noun for an animal that will never gather in a group again: an extinction of moa?

Extinction is a bit like climate change: it’s a natural process that has happened over millions of years. It is now running wild because of how 7.9billion people live on the planet. It’s huge and scary and upsetting. It sounds incurable and impossible to fix. And, like climate change, it’s more complicated than we realise.

In its simplest definition, extinction is when the last known individual of a species dies. It is very rare for us to know that it is happening when it happens — usually we realise afterwards. Animals or plants might be "functionally extinct" long before that — we can imagine a population with no females or a plant that cannot make fertile seeds, for example. "Local extinction" is when something no longer lives in your country or neighbourhood, though it might be thriving elsewhere. "Extinct in the wild" means the species is no longer found it its natural habitat, though some survive in captivity.

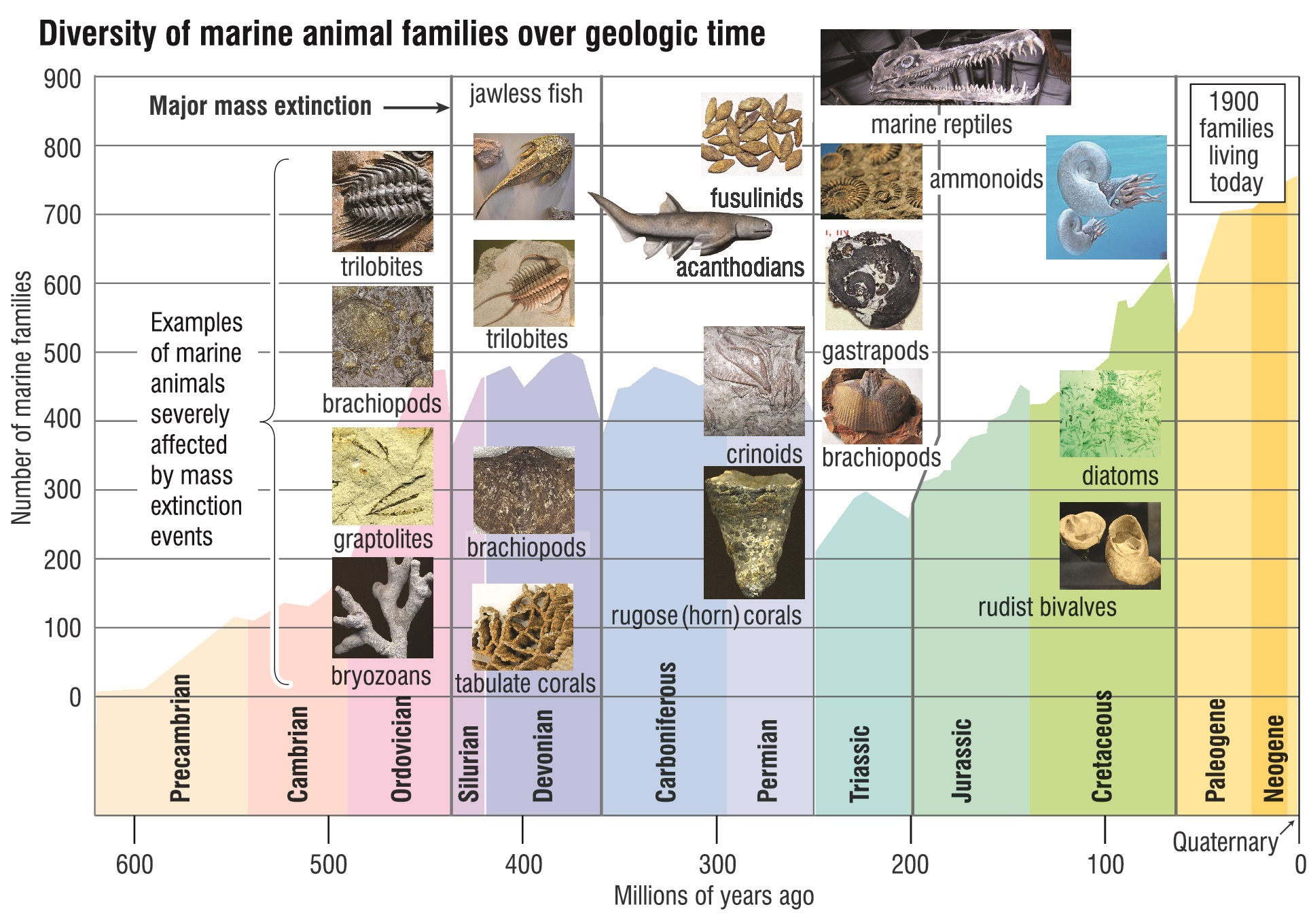

When conditions on Earth change radically, there is often an increase in extinctions, followed by rapid evolution to fill the gaps. We know of five major extinction events in Earth’s past. Scientists are increasingly worried that the sixth major extinction event is under way right now. We see statements such as "150 species lost per day" — while it’s probable that many species are lost every day, exact figures are impossible to know. Some models suggest that half of presently existing plants and animals may become extinct in this century. Most disappearances will happen quietly and never be noticed. Some species we lose will never have been recognised or described before they are gone.

When we think about extinct species, we tend to think about dinosaurs and dodos, mammoths and moas — big land animals. When we worry about future extinctions, again we think about tigers, cranes, rhinos, gorillas. Our approach to these endangered species is generally to protect their habitat. The creation of wildlife reserves such as national parks, if large and connected enough, can enable the ecosystem to save itself, preserving not only the visible target species (e.g., tigers) but also the many components of its home ecosystem, such as orchids, worms, and forest fungi.

If it is difficult to document and prevent on-land extinctions, it is so very much harder to do so in the oceans. Only a handful of marine species are recorded as having become extinct, probably not because they are especially resilient. More likely, they are especially hard to find and study. We don’t have collective nouns for species in the sea — just a "school of fish" and nothing whatever for barnacles (May one propose a "blister of barnacles?").

People have tried to protect parts of the ocean, using tools like taiapure and marine reserves. Limiting or forbidding fishing and dredging can make a real difference for some large species, such as crayfish. But not if there’s a stream nearby spewing forth dirt and pesticides and fertilisers every time it rains. Not if there are microplastics swirling in from the open ocean. Not if the water temperature is soaring, and the acidity is changing.

The number one issue in marine systems is water quality; and for coastal ecosystems, that means we need seaward-looking management of the land.

Ki uta ki tai is a phrase that means "from the mountains to the sea", encapsulating the important effects of freshwaters (both quality and quantity) and land use (forests and fields) on the coast and marine ecosystems. There is no place on the Otago coastline (nor indeed in New Zealand) where hills, rivers, coastline and sea are protected and managed together. In fact, our whole management system divides the land and freshwaters from the sea. Unlike the native tuna (eels), that weave their lives between the ocean and the rivers, we are far from achieving any kind of integrated approach.

The only way to slow down our potentially catastrophic loss of marine biodiversity is to change how we do things. We need to change our approach to environmental management, change and regulate what we put into the oceans, and develop our capacity to think about the whole, not just its parts. And we have to do it now. There are only 63 adult Maui dolphin left.

It would be a great shame if the collective noun for marine life becomes "an emptiness of oceans".

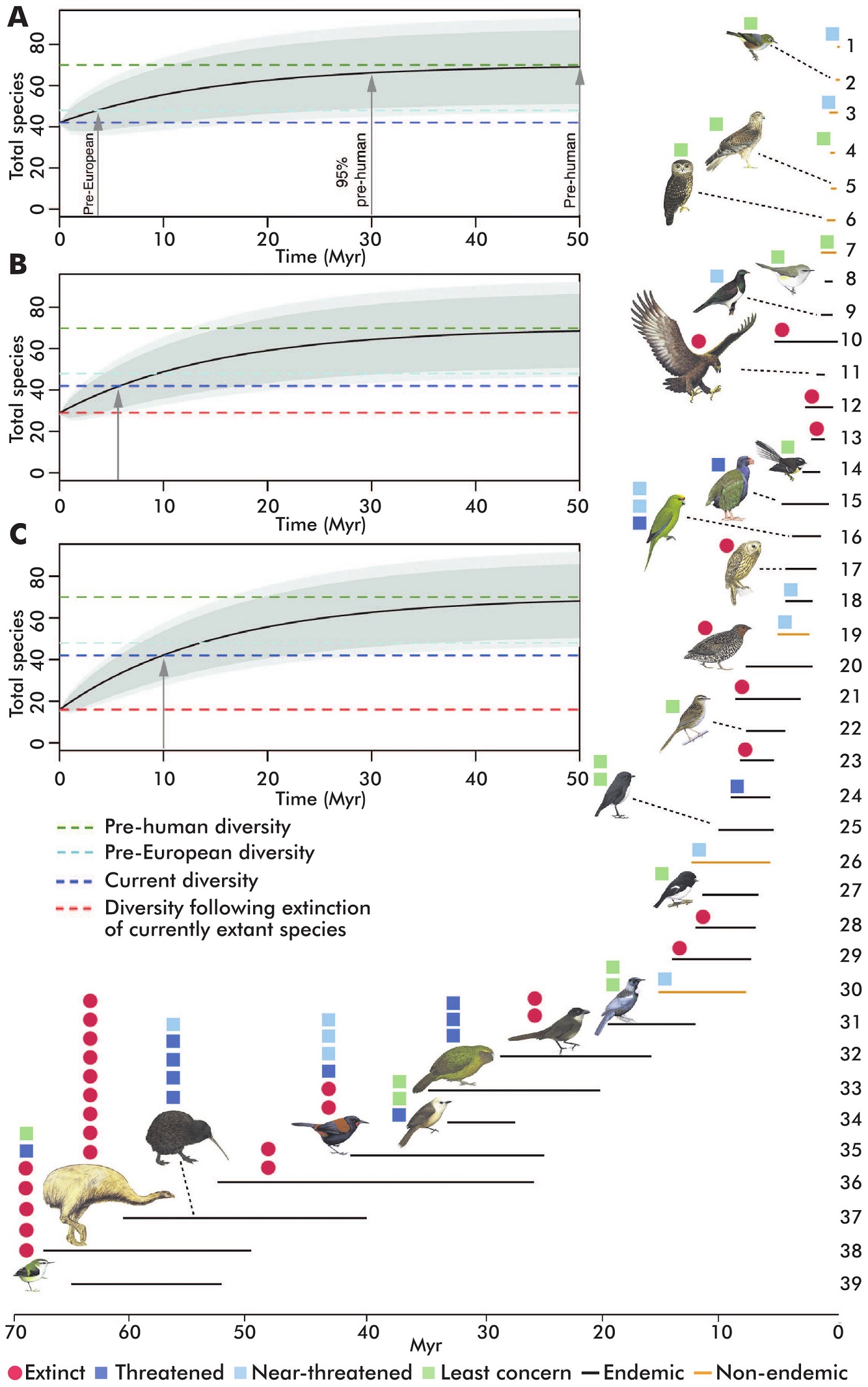

It took humans only a few hundred years to drive more than half of New Zealand’s bird species to extinction. Now, an international team of scientists, led by Dr Luis Valente, of Museum fur Naturkunde, Berlin, have calculated that it would take about 50 million years to recover the full diversity of bird species lost to human actions. Further, they found that if currently threatened species go extinct, it would take an additional 10 million years for New Zealand to achieve today’s level of species diversity. The graphic shows colonisation times and evolutionary return times for New Zealand birds. Coloured symbols above colonisation times represent all species present upon human arrival and those descended from that colonisation event. Plots show expected future bird diversity in New Zealand for a range of scenarios: (A) return time from current to pre-human diversity; (B) return time if threatened species go extinct; (C) if threatened and near-threatened species go extinct. Gray arrows indicate evolutionary return times. GRAPHIC: CURRENT BIOLOGY

Back from the Brink

The rediscovery of takahe in the Murchison Mountains was a breathtaking moment for New Zealand — when one of its extinct birds marched back on to the stage, large as life. In the sea, we tell the story of the coelacanth — a huge fish known only from fossils many millions of years old, then suddenly discovered living on the coast of South Africa. These lost-and-found stories give us hope. Maybe we’ll see a moa. Maybe they’ll find a plesiosaur. Maybe we can grow a Tasmanian wolf. But probably not. Our effort should be spent on preserving the biodiversity around us. At least we can spare our tamariki from wistfully wondering what it would have been like to see an actual dolphin, or hear a live tui.

What to do about it?

Each person can make a small difference, but many people can make a larger difference. Arguably the most effective thing we can do is to make our concerns known loud and clear to local and national government. Emails, letters, submissions, even a postcard can be quite effective.

Coasts in New Zealand are managed via coastal plans produced by regional councils. The Otago Regional Coastal Plan was produced in 1994 and modified in 2009 and 2012. Is it still fit for purpose? Does it reflect our current state of knowledge? When are they revisiting it? https://www.orc.govt.nz/plans-policies-reports/regional-plans-and-polici...

The Dunedin City Council is consulting on a management plan for Ocean Beach from St Kilda to St Clair — you can have your say right now about a special bit of our coastline. https://www.dunedin.govt.nz/council/council-projects/south-dunedin-futur...

The Department of Conservation is responsible for species management and species recovery plans — most of which are out of date or not actively being pursued. What are they doing to help our marine ecosystems thrive again? https://www.doc.govt.nz/about-us/science-publications/series/threatened-...

The Southeastern South Island Marine Protection Forum toiled for four years (2014 to 2018) to develop a network of marine reserves — from Timaru to Waipapa Point. Ministers agreed to progress the recommendations, but no progress has apparently been made since August 2020. When are we going to actually protect some of the Otago coast?

The Ministry for the Environment released Our Marine Environment 2019, with a clear setting out of the most pressing issues facing our coasts and seas. Number 1: native marine species and habitats are under threat. How is the Government doing on addressing them? https://www.mfe.govt.nz/publications/marine/our-marine-environment-2019