In Otago Harbour in the springtime, our shores teem with little pink shrimp-like critters, both swimming and stranded on the beaches. If you swim in Otago Harbour at this time, you’ll be hard pressed to keep them out of your togs. That’s Munida.

Munida gregaria is the scientific name for a small red crustacean that looks like a miniature lobster — that’s because it is one. One common name for it is the "gregarious squat lobster". It’s also known as "red whale feed", "lobster krill" and, in Spanish, "langostilla". Its Maori name "koura rangi" also describes its relationship to lobsters and crayfish.

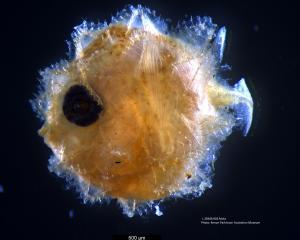

Squat lobsters start their lives as larvae, tiny zooplankton floating in the open ocean. When they reach the right size, larvae metamorphose into the small (1cm-2cm long) lobster-like "postlarva", a form suited for travelling long distances. Munida gregaria postlarvae gather in multitudes, staining the ocean red for miles, and swimming together — energetically flapping their tails — towards shore. This same species is found in Australia, New Zealand, Chile, Argentina, and Sub-Antarctic Islands — a very wide distribution for any kind of lobster.

When they reach a suitable shoreline, postlarvae sink to the bottom in order to claim a territory and become adults. But there are already adult Munida on the seafloor, unwilling to share space with newcomers, so the postlarvae float on. Many of the postlarvae wash up on beaches, to become stranded by the tide. Many more are eaten. Nevertheless, some Munida postlarvae grow into adults: small lobsters, up to 7cm long, which live two-three years, usually in deepish water (about 30m-40m).

Otago Harbour is a place where you can easily see two kinds of gulls, two kinds of terns, penguins, and three kinds of shags, with albatross, mollymawk and shearwaters on a windy day. All of these birds, plus sparrows and starlings, eat Munida. So do seals and sea lions. Below the waves, fish, squid, octopus and even the odd passing whale also dine on the pink squat lobsters. Nowadays anything that people eat ends up in short supply, so Munida is a reliable coastal food in springtime. Maybe we should just leave it alone.

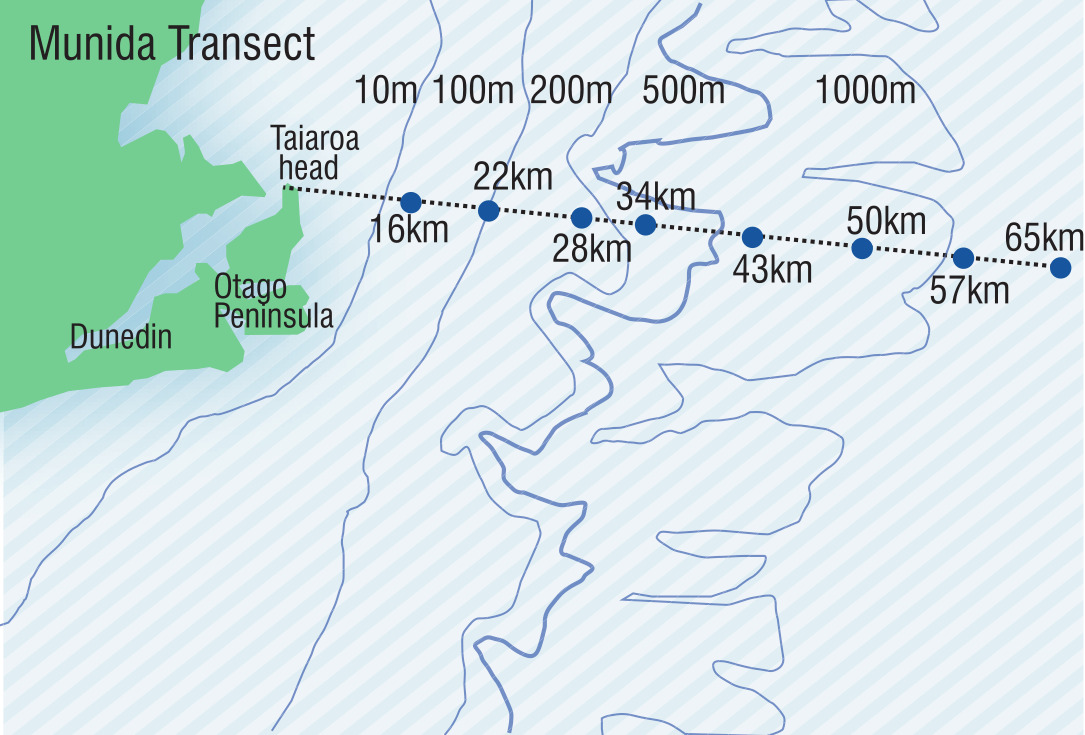

In 1966, Otago scientists named their new research vessel for the abundant squat lobsters that regularly covered local beaches. Later, scientists named "The Munida Transect" after the boat. It’s a particular path that stretches 65km out to sea from the tip of Otago Peninsula, along which scientists have been measuring plankton, sea-water chemistry, and water masses since the late 1960s. The CO2 and ocean pH research along this transect is one of the longest-lived and best-monitored in the world. Among international climate scientists, the Munida Transect is famous — even if they don’t know about the little squat lobsters of Otago.

Abby Smith is a professor of marine science at the University of Otago.