Why do they play hide and seek? Delicious creatures hide to avoid being eaten. Hungry creatures hide in order to sneak up on potential prey. Some hunters even use parts of their bodies as bait, luring their victims closer.

Another strategy is to wear a costume — to look like a more-dangerous alternative. Young zebra sharks, for example, are striped and swim like sea snakes. But it’s not just fish that do this: in the seagrass beds off Washington state, an edible bug (the amphipod Stenopleustes) adopts the colour pattern, shape and even the slow glide of a local inedible snail (Lacuna) in order to avoid being eaten — and it works. Fish only seem to catch these bugs-in-disguise when they are forced to swim.

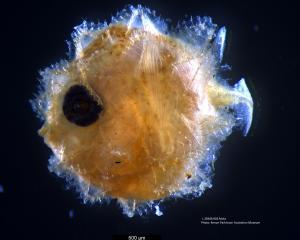

Decorators, on the other hand, don’t use pigment and mirrors. They collect items from the seafloor and glue them on, building a "hide" on their own shell. Decorator crabs are common all over Aotearoa New Zealand seashores. Their shells are festooned with hooks (like Velcro), so they just pick stuff up and hook it on. Some crabs will spend time moving their decorations onto their new shell after they have moulted. Similarly, the deep-water "carrier snail" glues clamshells or stones onto its own shell. And the clam shells are invariably attached "cup-side-up" to show how empty they are. Nothing to see here, just swim past.

Then there’s the tactic of distraction. Many fish have a tail spot. Its job is to look like an eye, so that a predator who gets close only gets a mouthful of tailfin instead of a yummy head. Other fish are patterned to disguise the actual eye with striping or colour change right around the eye, or have strong complicated patterns to break up their shape, particularly when in a school of similar fishes. Some open-ocean fish, such as the anchovy (kokowhāwhā) are silver mirrors, very difficult to see in a sun-lit sea, especially when schooling. Some fish are nearly transparent; others are iridescent.

Life is all about trade-offs. While coloration may help keep marine organisms safe, it also has costs. They need to produce the special cells, the pigments, the glue. So it must be worth it. If all non-camouflaged critters get picked off, the survivors pass on their tricks to the next generation. And so marine creatures have become more and more innovative, using all kinds of tricks to fool each other, and us.

Abby Smith is a professor of marine science at the University of Otago. Each week in this column, one of a panel of writers addresses issues of sustainability.