Serendipity has marked the distinguished career of Prof Robert Webster's international fight against the deadly influenza virus.

Similarly, coincidences will cause the next monster influenza epidemic, for which we are woefully unprepared, the former Otago researcher tells Bruce Munro.

It is hard to believe that the erudite and engaging voice on the phone belongs to an 86-year-old.

But there is no denying that renowned virologist Prof Robert Webster, on a call from his home in Memphis, Tennessee, was born in Balclutha, Otago, in 1932. Nor that the story he is recounting, of a surprising yet definitive moment in the battle against influenza, happened half a century ago, to him.

"It started off, more or less, as a joke,'' Prof Webster recalls.

One day, in 1967, he and fellow future influenza expert, the late Dr Graeme Laver, were walking on a beach in New South Wales, Australia. Noticing numbers of dead muttonbirds (shearwaters) washed up on the shore, and knowing that terns had been killed by influenza in South Africa six years previous, they wondered aloud whether these birds too had died of the `flu.

"Laver and I decided it would be a bit of a lark to head to the muttonbirding sites on the Great Barrier Reef, on a hunch that they might indeed be infected with influenza.''

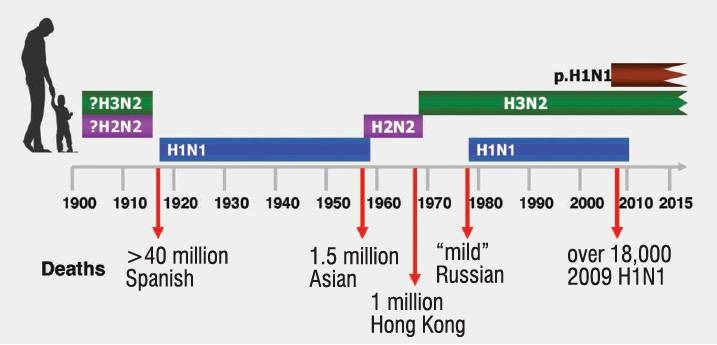

In the late-1960s, influenza, even though it had killed tens of millions of people worldwide in 1918 and had killed 1.5 million in Asia in 1957, still held many of its secrets.

During the 1930s, it had been proven that influenza was not caused by a bacteria but a virus. Later, two different types of influenza virus were identified (The final count would be three, with a fourth proposed but as yet unproven).

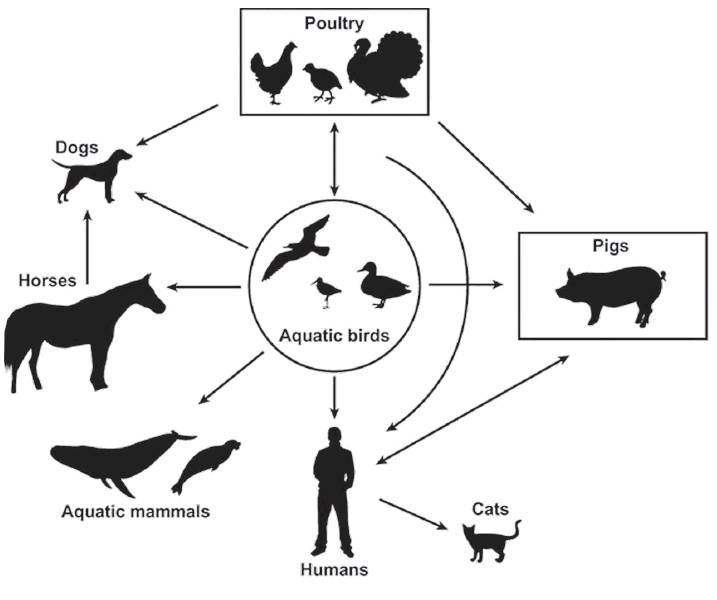

By mid-century, it was recognised that different strains of the virus made it difficult to create effective vaccines. The big question then was, did influenza pandemics occur because there were lots of different strains of the flu circulating in the human population or because humans were somehow being infected with various strains carried by animals?

Profs Webster and Laver, then junior scientists in their mid-20s, pitched their muttonbird research idea to the head of the microbiology department at the Australian National University (ANU), but were rebuffed. So, they took it to someone at the World Health Organisation who they knew supported the theory that pigs were the source of human influenza pandemics. They received their funding. Then the ANU also came on board.

During the next several years, the men, along with their families and other scientists, made seven trips to Great Barrier Reef islands to sample muttonbirds for the flu virus.

"We generally spent the days swimming and snorkelling on the most fabulous coral reef in the world, harvesting fish and lobster for our meals. The evenings were spent doing the science,'' Prof Webster says.

Two significant discoveries were made.

They found that some of the muttonbirds had indeed been infected with the influenza virus. They also discovered that harmless versions of influenza viruses could be carried by healthy birds, but that the same viruses could change and become killers.

These were vital insights into the origins of pandemic flu viruses.

But, as Prof Webster admits, they were breakthroughs born of a chance stroll on a beach that birthed an idea which was part serious scientific inquiry and part young men looking for excitement and fun.

"It was a bit of both, to be absolutely honest. As students and junior staff, we were looking for some adventure on the barrier reef with our families.''

There was still a long way to go. In the future lay breakthroughs (which Prof Webster would lead or contribute to) that would prove that wild aquatic birds are indeed a major reservoir of the viruses that become human pandemics and that the viruses can cause no trouble to the birds but become killers when they spread to other animals and humans. There would also be discoveries that would lead to the development of Tamiflu, still the world's most effective treatment for people infected with influenza.

All that lay ahead. But it was a start towards understanding and trying to prevent recurrence of the most deadly recorded human influenza pandemic, the 1918 Spanish Flu.

Chance events, as much as deliberate decisions, shape history.

THE Spanish Flu, which 100 years ago killed somewhere between 25 million and 100 million people, is an astonishing case in point.

That particular virus was a nasty piece of work.

Prof Webster, whose team took early steps towards others' later successful attempts to decode it, describes how the 1918 flu attacked people.

"A perfectly healthy young person ... would develop a headache and muscle soreness, their body temperature would rise as high as 41.1degC and some people would become delirious.

"The person would be so weak they would fall down; mahogany-coloured spots would appear on the face, which itself would turn blue or blackish from lack of oxygen; and the person would bleed from the ears and nose.

"The lungs would fill with blood and the person would essentially drown in their own blood.''

The 1918 flu erupted on both sides of the battle lines in the dying stages of World War 1, probably brought to Europe by United States (US) soldiers infected with a less deadly strain of the flu.

Why it became a monster killer comes down to the specific conditions the virus encountered in the mud and blood-filled trenches. Horrendous overcrowding and unbelievably unhygienic conditions allowed it to spread quickly. Chemical warfare, specifically gases that are known to cause mutations, enabled the virus to develop terrible qualities. Then, wartime secrecy allowed soldiers to carry it home and infect unsuspecting civilian populations worldwide.

After Germany and its allies surrendered, negotiations were held in Paris, France, to determine how much reparation would have to be paid. US president Woodrow Wilson wanted Germany to be shown leniency. French president Georges Clemenceau wanted the Germans severely punished.

Wilson threatened to walk out. But then he contracted the flu. He survived, but with a markedly changed personality.

It is known that the virus did damage some sufferer's brains, Prof Webster says.

Suddenly, Woodrow gave in to all the French president's demands. Germany was loaded with an enormous war debt.

The ensuing economic hardship and resentment helped the rise of Adolf Hitler and Nazism.

Without the 1918 flu, there might have been no World War 2.

"I can't guarantee it wouldn't have occurred. But, I speculate that it wouldn't have occurred,'' Prof Webster says.

He was 13 years old when World War 2 ended.

A few years later, he left the family farm at Pukepito, near Balclutha, and enrolled at the University of Otago to study chemistry. But a lack of high school chemistry and a chance meeting with the head of the microbiology department saw him changing course.

Fate stepped in again early in his post-graduate career. Interested in studying the rabbit-killing virus, myxomatosis, he applied to a relevant research laboratory at ANU.

But, the day he arrived, he was told the research group was full and he was being put in a group studying influenza.

"I remember sitting there thinking, 'Oh my God, I know nothing about flu'.''

He was far from happy. But, other than resign, there was nothing he could do about it. He readily agrees that coincidences have played a big role in his life and career.

"It's a case of making the most of these things. Sometimes, they work out.''

By the early-1970s, Prof Webster was living in the US, working in the departments of microbiology and immunology at St Jude Children's Research Hospital, in Memphis.

In 1975, the hospital became a World Health Organisation influenza research collaboration centre. The same year, with his reputation rising, Prof Webster was invited to take part in a joint American-Soviet influenza research programme.

He was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1989, was recognised by the US National Academy of Sciences nine years later and made a Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand, in 1990.

At Christmas time, in 1997, he was in the thick of it when the first human outbreak of H5N1, bird flu, took place in Hong Kong. People were catching the virus from infected poultry in the city's more than 1000, crowded, live-bird markets .

At one point, 30% of those getting sick were dying.

"The huge concern was that the virus might start to spread from human to human, which could lead to a global catastrophe.''

Prof Webster, and the international team of young scientists he had trained, played a vital role in identifying the virus. He was part of the advisory group that called for all live poultry in Hong Kong to be culled. As a result, there were no more human cases of H5N1 at that time.

In 2005, Prof Webster established the Webster Family Chair in Viral Pathogenesis, at the University of Otago.

The next year, the Smithsonian Institute, in an article about him, dubbed Prof Webster "the Flu Hunter'' for his significant, decades-long contribution to understanding and fighting influenza.

Now in his ninth decade, Prof Webster, still based at St Jude Hospital, continues to travel, research, write and speak on the flu virus.

His gravest fear is that an influenza pandemic on the scale of the 1918 flu is not a matter of "if'', but "when''.

In that catastrophic eventuality, he predicts chance will once again play a decisive hand.

All of the distinctive qualities that made the 1918 flu so deadly are out there, but scattered among different viruses, he says.

And nature is continually "shuffling the deck'' - viruses are always mutating.

"The cards are all out there. Sooner or later there will be one that could be as bad as 1918.''

All it needs, he says, is the right combination of factors to allow viruses to come together, share genetic material, hit the jackpot and proliferate.

A combo such as that presented by the hajj; the annual Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca, in Saudi Arabia. Every year, more than three million people from dozens of countries congregate in the 400m by 800m, Great Mosque of Mecca during the final month of the Muslim lunar year.

"Just imagine if that virus got into the hajj. The 2009 flu got into the hajj. People come from very depressed parts of the world ... [some of which] don't have particularly good health conditions. That would be the perfect place for it to occur.''

What about hot spots such as the Rohingya refugee camps, on the border of Bangladesh and Myanmar, where camps of more than 600,000 people are crowded together in often squalid conditions?

"Exactly,'' Prof Webster responds. "What a bloody good suggestion. That's exactly the sort of stressful situation where that thing could explode.''

His efforts to monitor and mitigate influenza's deadly potential continue.

"We are watching what is happening in the huge poultry markets in Bangladesh. We tell them what viruses they've got and how it's changing.''

He is encouraging the development of more drugs to tackle flu.

"There is still really only one drug at the moment, Tamiflu, which came out of the barrier reef work.''

But there are now some drugs in the pipeline, from Japan, that are looking hopeful, he says.

Prof Webster is also keeping a keen eye on the search for a universal vaccine that would be effective against all strains of the virus. It is closer than the goal of producing flu-resistant pigs and poultry, but, at present, is still a "pipedream'', he says.

He warns there are steps that could be taken, but which are not, that leave us globally vulnerable to another catastrophic flu virus.

Crowded markets selling live chickens and ducks are the perfect breeding ground for new viruses that can be transmitted to humans and then develop human-to-human capabilities.

"We have to get rid of those damned poultry markets.

"They really have to go ... but it's not going to happen easily.''

New Zealand may seem a long way from where a potent flu virus could emerge. But nowhere is more than one or two plane flights from anywhere on the globe.

"One of the things that aeroplane manufacturers don't like to do is to put in those hepa filters to stop disease spreading ... Only a few airlines do it.''

If a killer flu did start spreading, the WHO influenza network would kick into action to identify it and produce a vaccine.

"But it would still take us six months to make a vaccine. What are we going to do in the meantime? The flu doesn't stop. It gets on an aeroplane and it's all over the world.

"If the flu is a really hot one, it could take out millions of people before we could do a damned thing.

"[Eventually], nature is going to shuffle the perfect hand.

"And if nature gets it right, then we are in the poo.''