The spectacular building is surrounded by spacious gardens, tennis courts and monuments. Paintings of monarchs adorn the walls. But the impressive setting is at odds with its present purpose.

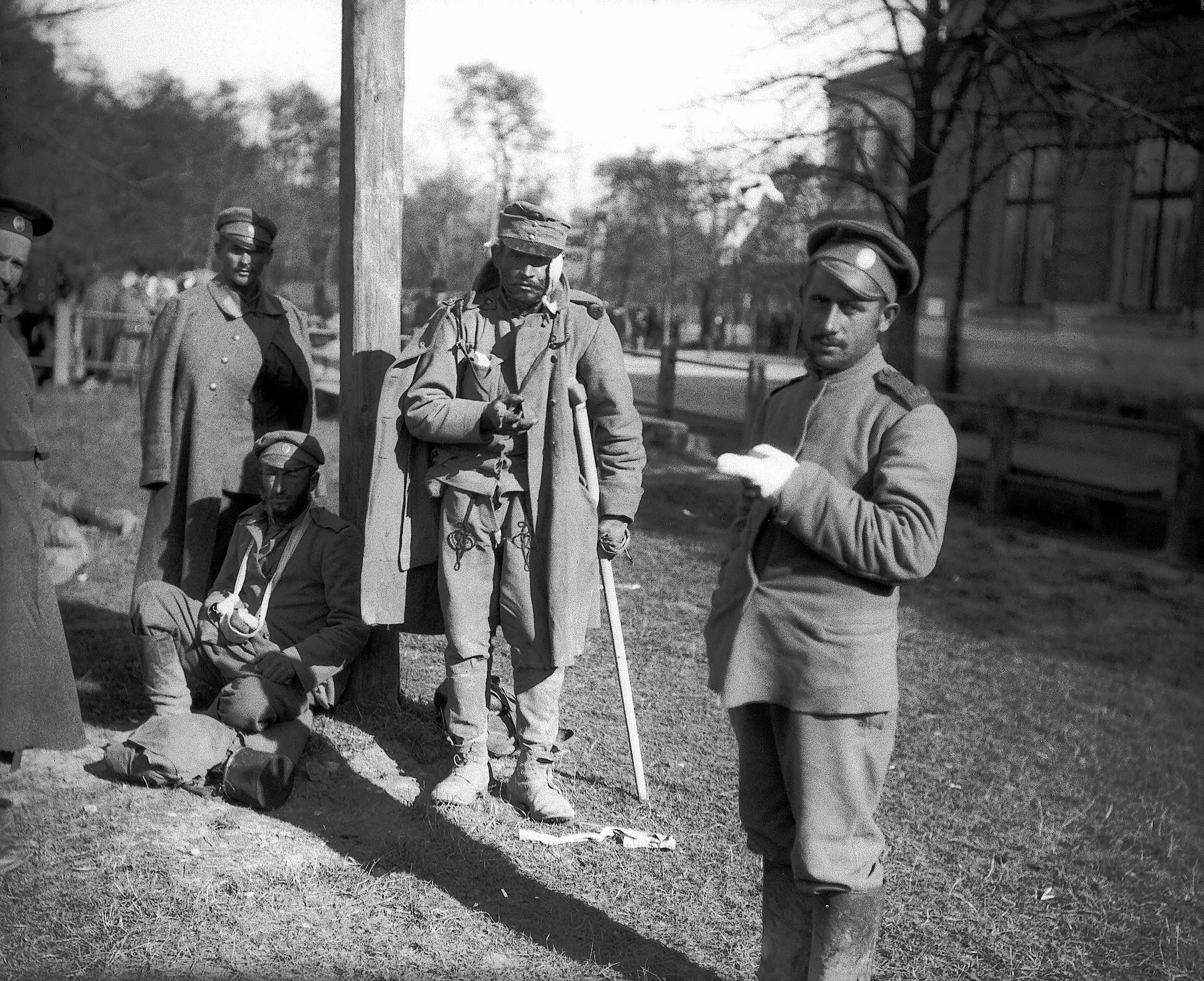

Inside, two surgeons struggle to cope with an influx of injured men, many of whom will need limbs amputated. The language barrier makes conversation between doctors and patients almost impossible, anaesthetic is in short supply and even if the men make it through surgery, there is the ever-present risk of secondary haemorrhage.

These were the conditions Waimate doctor Herbert Clifford Barclay faced while working as a surgeon in a Red Cross hospital near the Eastern Front during World War 1.

Barclay wrote detailed letters to journalist friends in New Zealand and, because he was well-known in his community, they were published in the Waimate Advertiser and the Christchurch Sun.

Canterbury author David Lockyer discovered the accounts while researching Barclay’s colleague, Dr Margaret Cruickshank, and has collated them in a self-published booklet, A Doctor Writes Home, 1914.

The son of a Presbyterian minster, Barclay was mayor of Waimate, president of its orchestral society and a member of the Waimate Rifle Volunteers.

After graduating from Otago Medical School in 1889, he established the town’s first private medical practice and hospital, also serving as surgeon-superintendent of its public hospital. In 1897, he invited Dr Cruickshank, New Zealand’s first registered woman doctor, to join his practice.

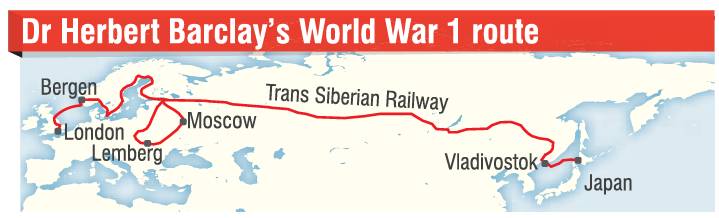

In May 1914, the 48-year-old took leave of absence to undertake further study in England. He planned to travel via Japan and India but on the way, World War 1 broke out.

In a cable home, he told his wife and four children his plans had changed and he now hoped to travel to England via Russia. He arrived in Petrograd [St Petersburg] after a ‘‘tedious’’ 22-day journey on the trans-Siberian railway and decided to offer his services to the Russians.

Barclay was anxious to get to the front but before that could happen, he was presented to the dowager Empress, the mother of the last Russian Tsar, at a summer palace on the island of Neva. Maria Feodorovna expressed her pleasure at seeing an Englishman with her troops and applauded the Anglo-Russian alliance.

By mid-September, the Kiwi doctor was helping to establish a hospital in the city known in German as Lemburg/Lemberg (now Lviv in modern Ukraine).

Long under Austrian rule, Lemburg was the administrative centre of Galicia, a region spanning present-day western Ukraine and southeastern Poland. Its population included Roman Catholic Poles, Jews and Greek Catholic Ukrainians.

Historians consider the Battle of Galicia in August and September of 1914 to be one of the most significant battles along the Eastern Front. It resulted in the Russian army forcing the Austro-Hungarian armies out of Galicia and holding the region for nine months.

The hospital where Barclay would operate on Russian soldiers was based in the ‘‘magnificent’’ four-storey building that had been the infantry barracks of the Austrian Cadets.

‘‘We have done a little looting in the upper attics, where we dug out some fine Austrian pictures of military heroes and monarchs, and adorned our rooms with them,’’ he wrote.

‘‘Two hundred wounded lie here now four days and yet unattended to, except the original first aid dressing in the field. It will be another day before we can unload and fit up our trainload of goods ... Things are lively around us today. The Poles and Jews in the town have revolted, and firing and bombs are going off ad lib. You would be amused, while unpicking seaweed for making pillows, and helping to cut mackintosh cloth for draw sheets, to pause for a moment’s rest, just to judge the distance of the last burst of rifle shots. It adds great zest to existence. Under the circumstances we are arming for self-protection, as the Red Cross is not necessarily very sacred in a town fight. However, nichivo [it’s nothing], as the Russians say.’’

The hospital had 250 beds with the capacity for 150 more. Any day, the staff expected to be sent out to establish other smaller hospitals nearer the front.

‘‘The operative work has so far been pretty persistent and hard, but will no doubt grow worse,’’ he wrote on September 22. ‘‘There are only two operative surgeons on the staff, a Dr Crepes (a Jew of French extraction) and myself. We have an anaesthetist and a physician. We have four tables going in the operating room: sometimes from 9am ’til dark, but always ’til 2pm. And really I pity many a man: I wish he had died in the trenches, and so, poor devil, must he. It gets too much for me.

Many cases put on the tables by the physicians for dressings get no anesthetics, and to operate amid the hideous wails and the occasional scream of others is distressing beyond measure. Most of the cases we are dealing with now have laid for a fortnight with compound fractures, soaked in decomposing matter, with dressings unchanged, and present pictures of misery and loathsomeness hard to realise.

There is no use trying to save most of the limbs. Off they have to come. But they are luckier really than those we try to save, for the agony of changing the dressings and splints and attempting to straighten their limbs is much greater than the suspense or fear in the firing line. Many, I have no doubt, wish themselves dead.

But the Russian soon recovers his equilibrium. His capacity for good humour and cheerfulness is unbounded, and half an hour afterwards in the ward the screaming poor beggar of the operating table is smoking a cigarette and all smiles, and yes, sometimes even grateful ...’’

On September 29, he wrote of an ‘‘invasion’’ of 400 patients arriving at the hospital at midday.

‘‘It was tremendous work, four of us attending them ’til late at night, many involving operations ... About 9pm, Dr Crepes and I (we can only speak in French) decided to go out, and ease our fatigue and headaches for a little, but were recalled to be told the news from the front was not too good. All the new men admitted who could walk must be evacuated first thing in the morning. We must all be prepared to leave at short notice.’’

The Germans had been reinforcing the Austrians on the ‘‘fighting line’’ 120km away and there was concern they would recapture Lemburg. However, some staff had volunteered to remain with the patients who could not be moved and Barclay wrote that he ‘‘would not mind staying’’.

‘‘It has been feared all week that the Germans from Grodno and Cracow would get in rear of us and cut us off from Russia altogether ... I write this in case my chance of posting it should slip by ...’’

But several days later, he reported the Russians seemed to have kept the enemy at bay and although the hospital staff had packed, they had not moved: ‘‘As we have cleared most of our patients out, we have had a few days rest; and really it was badly needed.’’

In another letter, the contrast between the nightmarish war and the elegant buildings and charming landscape was again apparent.

The hospital was seeing hundreds of patients a day, aeroplanes reconnoitered the area at night and lights had to be put out, meaning the work of the doctor on night-duty was ‘‘not carried out under the pleasantest circumstances’’.

However, a recent snowfall had created a magical atmosphere.

‘‘Everything froze in the neighbourhood, and the large tennis courts of the Austrian Infantry Cadet Barracks were converted into a natural skating rink.The beautiful Kidinskiegi Park, with its ponds, its hills and dales, and magnificent fir trees were covered in a mantle of snow, magnificent in its beauty, especially at night time, when the city lamps were lit. Intermissions from hard work, gruesome sights and sleepless nights found the staff bob-sleighing or skiing in the park, or [skating] in our own grounds ...’’

In December, Barclay decided it was time to continue on to England, first visiting ‘‘Kief’’ [Kyiv], Moscow and Petrograd courtesy of a kindly Russian commandant. With usual routes disrupted by war, he then travelled to Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Norway before taking a ‘‘little boat’’ from the coastal port of Bergen across the stormy North Sea.

Once in England, he joined the Royal Army Medical Corp as a major and worked as a surgeon until 1918.

After the war, he established a private medical practice in Kent, dying in 1932, apparently estranged from his New Zealand family.

Mr Lockyer says his story had a sad postscript.

His eldest son, Clifford Clapcott Barclay, was killed on his 22nd birthday, the day of the Gallipoli landings. Then, in November 1918, his colleague in Waimate, Dr Cruickshank, died after attending patients during the influenza epidemic.

Barclay was a ‘‘forward-thinking’’ man, who published textbooks for nurses and encouraged Dr Cruickshank to work alongside him when women found it difficult to establish themselves as medical professionals, according to Mr Lockyer, who published a biography of Cruickshank, Beyond the Splendours of the Sunset, in 2014.

He also expressed admiration for the Russian people when there was still anti-Russian sentiment among the public and apprehension about possible Russian territorial ambition when the war was over.

Highly-skilled and fiercely independent, he did not tolerate fools and was something of a loner: ‘‘His career sort of controlled his life.’’

The war took its toll on Barclay and that would have influenced his decision not to return to New Zealand.

‘‘He would have been a different man. The world had moved on...’’

‘‘The changes he’d been through would have had a major effect on him.’’