The animals themselves came in two kinds: those with backbones and those without.

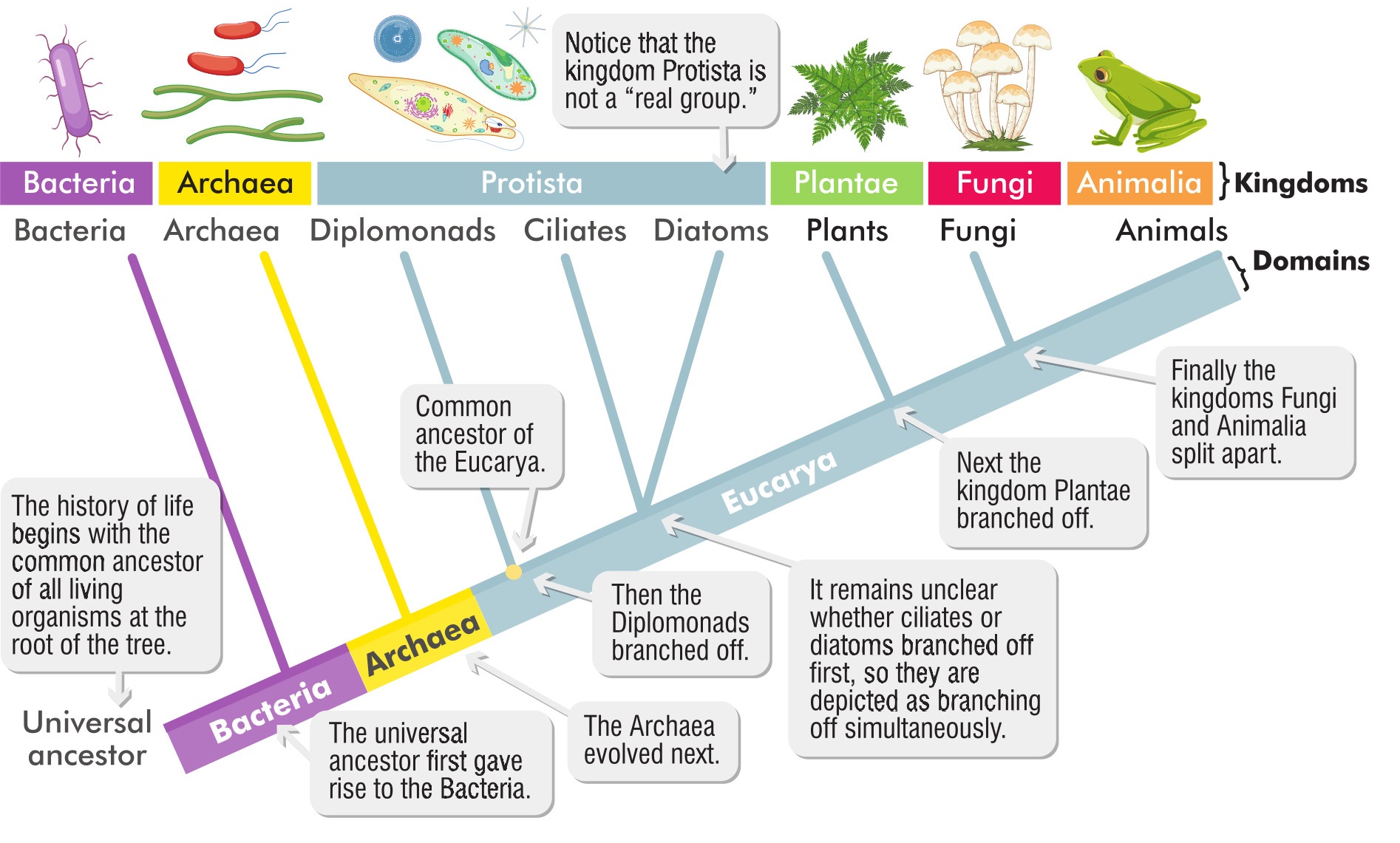

Back the 1700s, Carl Linnaeus defined two kingdoms, the Regnum Animale and the Regnum Vegetabile, with the next two kingdoms arriving after the invention of the microscope. In those days, decisions about relationships were made based on how things looked and what they did.

From about the 1970s, we became able to determine the exact sequences of the genes that make up living things — and from there we could find out a lot more about relationships. After all, the only place you can get genes from is your ancestors, and sometimes genes reflect a very long whakapapa indeed.

The technology needed to isolate DNA, untangle and break it into pieces, make lots of copies of particular bits and then list its components in exact order is complicated and took a lot of doing. Amazingly, nowadays people just order a kit and do it. It used to take days and days to laboriously unravel one gene from six critters; nowadays you can do 70,000 sequences from 24 creatures in the same time, and for about the same cost.

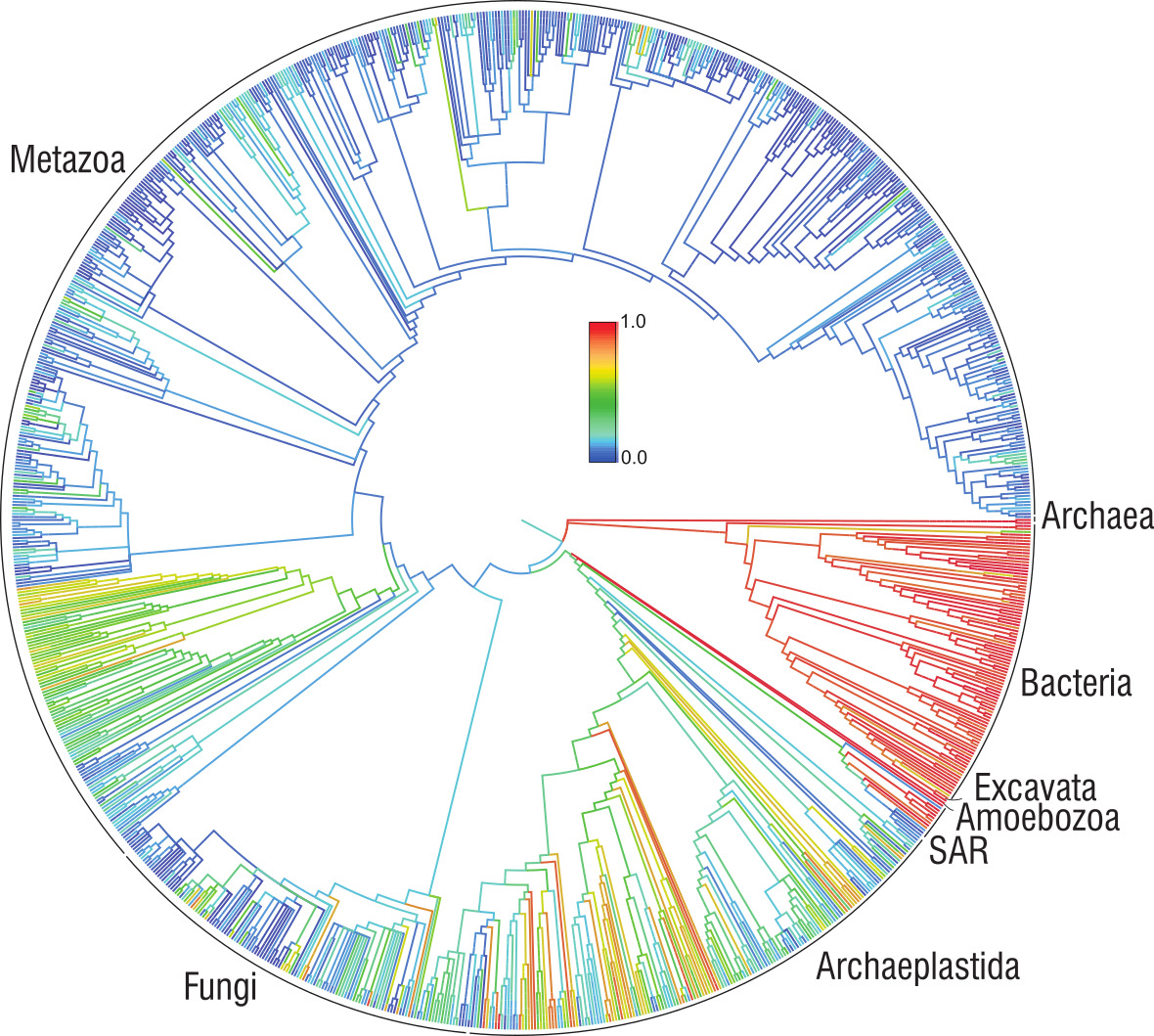

Like a family tree, the phylogenetic tree shows us how related things are. So in the tree that describes living primates, the human branch is closest to the chimpanzee branch. The other thing this tree shows is how far back in time the different species branched off. Ten million years ago, there were no chimps, gorillas, orangs or people - just a common ancestor that was a bit like all of us, and is now extinct.

Can we get DNA from extinct organisms? In Jurassic Park, amber made from dried tree sap contained mosquitoes which had drunk from the blood of dinosaurs - and scientists collected that DNA to grow dinosaurs. Sadly, DNA just doesn’t last that long. But we are beginning to be able to collect and sequence DNA from recently extinct organisms. Could New Zealand one day host "Moa Park"?

The latest cool thing in genetics is sequencing of what is known as eDNA: DNA collected from the environment. That’s what Otago’s Prof Neil Gemmell used when he went to Loch Ness to search for monsters. You don’t collect DNA from a specific critter, you just sequence everything in the water and match it to known patterns. This works very well if most of the species possible have already been sequenced.

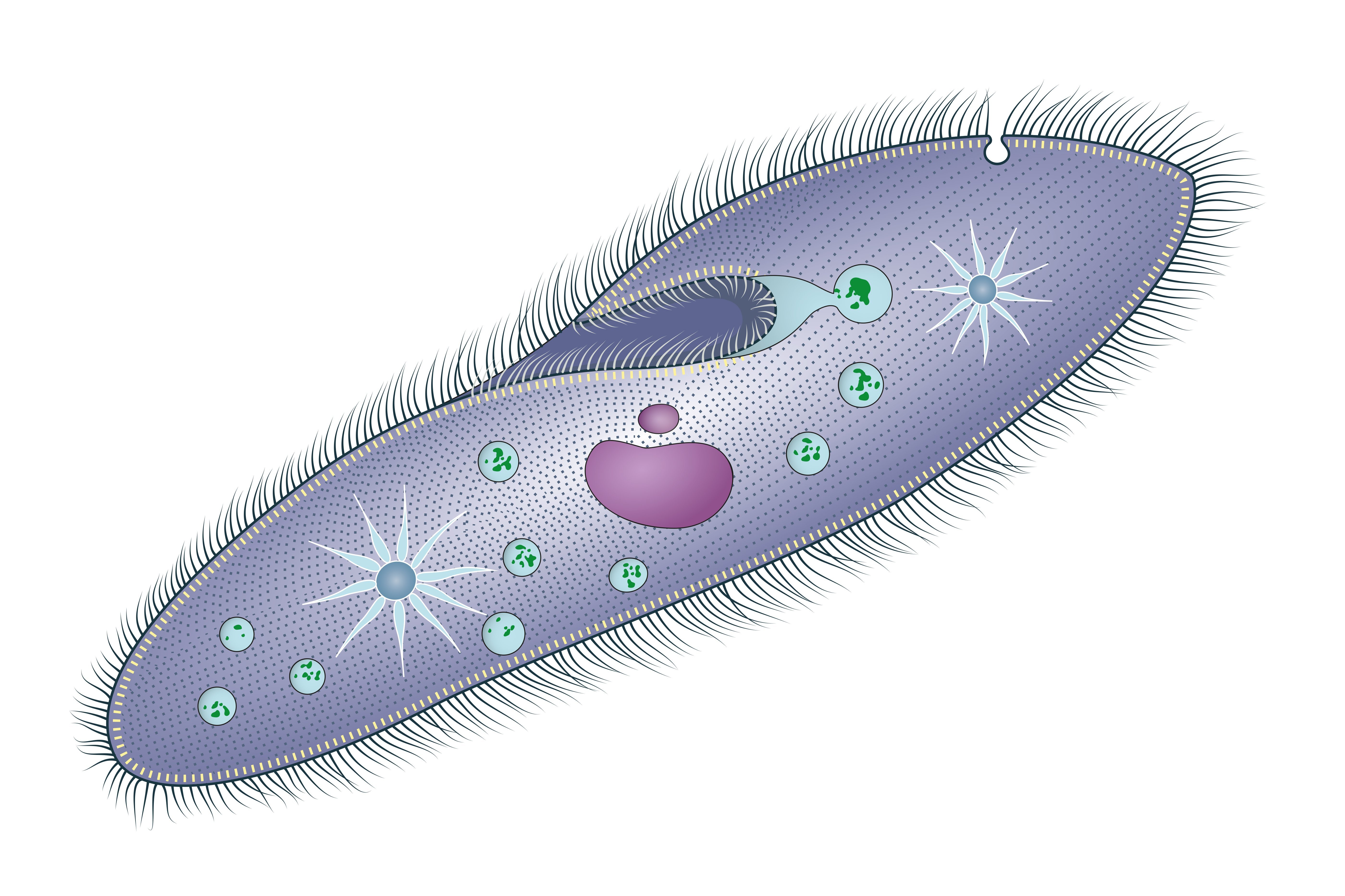

Another Otago biologist, Dr Gert-Jan Juenen, has been studying marine eDNA - finding out which fish and mammals have lived in different marine waters just by sequencing the tiny bits they leave behind as they swim through. His big problem is throughput. You have to filter a lot of water to get a little bit of DNA. Recently, though, he’s been solving that problem by enlisting the help of an animal that filters water all day and all night - the humble sponge.

As if that isn’t awesome enough, lately Gert-Jan and his students have been investigating whether you can get DNA from preserved sponge specimens sitting in museums that were collected decades ago. We might be able to describe changes in distributions of fish and marine mammals and birds over the last century just by sampling the juice of an old sponge.

We have all become aware of the usefulness of genomic sequencing as we have used it to identify Covid-19 variants and where they come from. Sequencing is also how we have been looking for traces of the virus in wastewater. Similarly, the development of genetic barcoding means we can identify a tree from its pollen, viruses without a microscope, or the diet of a fish from its stomach contents. Genetic sequencing is a powerful thing, and a lot of modern science depends on it.

You’ll notice I didn’t tell you how many kingdoms we now divide life into. That’s because it’s controversial. Some say five, rather more go for six, a few for eight. In the end, kingdoms (and other groupings such as classes, orders, families) are really just categories that help us to sort out the 10 million to maybe a trillion (who really knows?) species of life on Earth. Giant phylogenetic trees, showing as much of life as they can, are astonishing graphics, inspiring in a kind of incomprehensible way. The Open Tree of Life is a circle of branches that includes 2.3 million species; each branch has at least 500 species. Humans occupy a tiny little space somewhere about 10o’clock on the circle. It’s strange to think that one tiny species has such a lot of influence over all the rest of the diagram.

Abby Smith is a professor of marine science at the University of Otago. Each week in this column, one of a panel of writers addresses issues of sustainability.