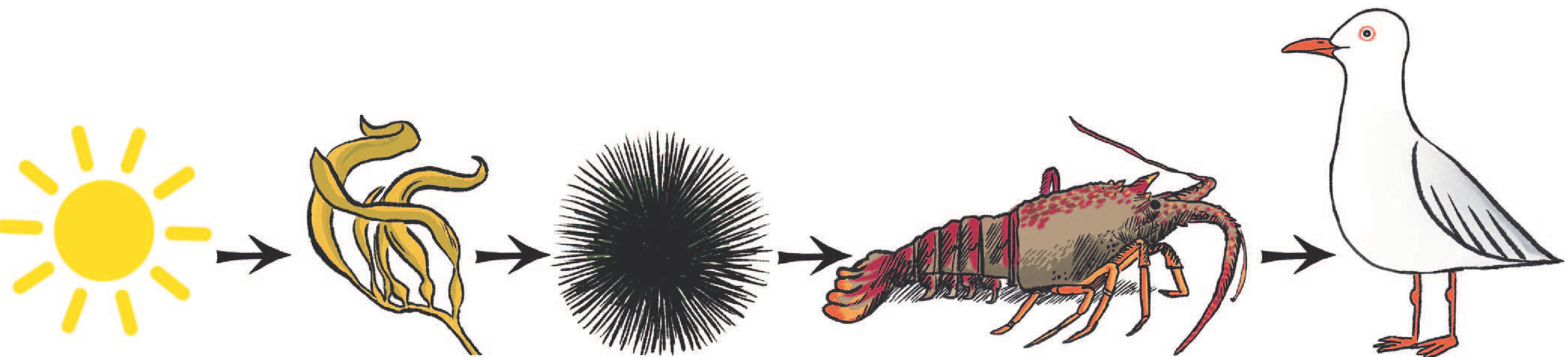

Life on Earth is a miracle of connectedness. In its simplest form, a plant collects energy from the sun and grows leaves. Some small creature eats the leaves, and then a larger creature eats the plant-eater. This sequence of connections is known as a food chain.

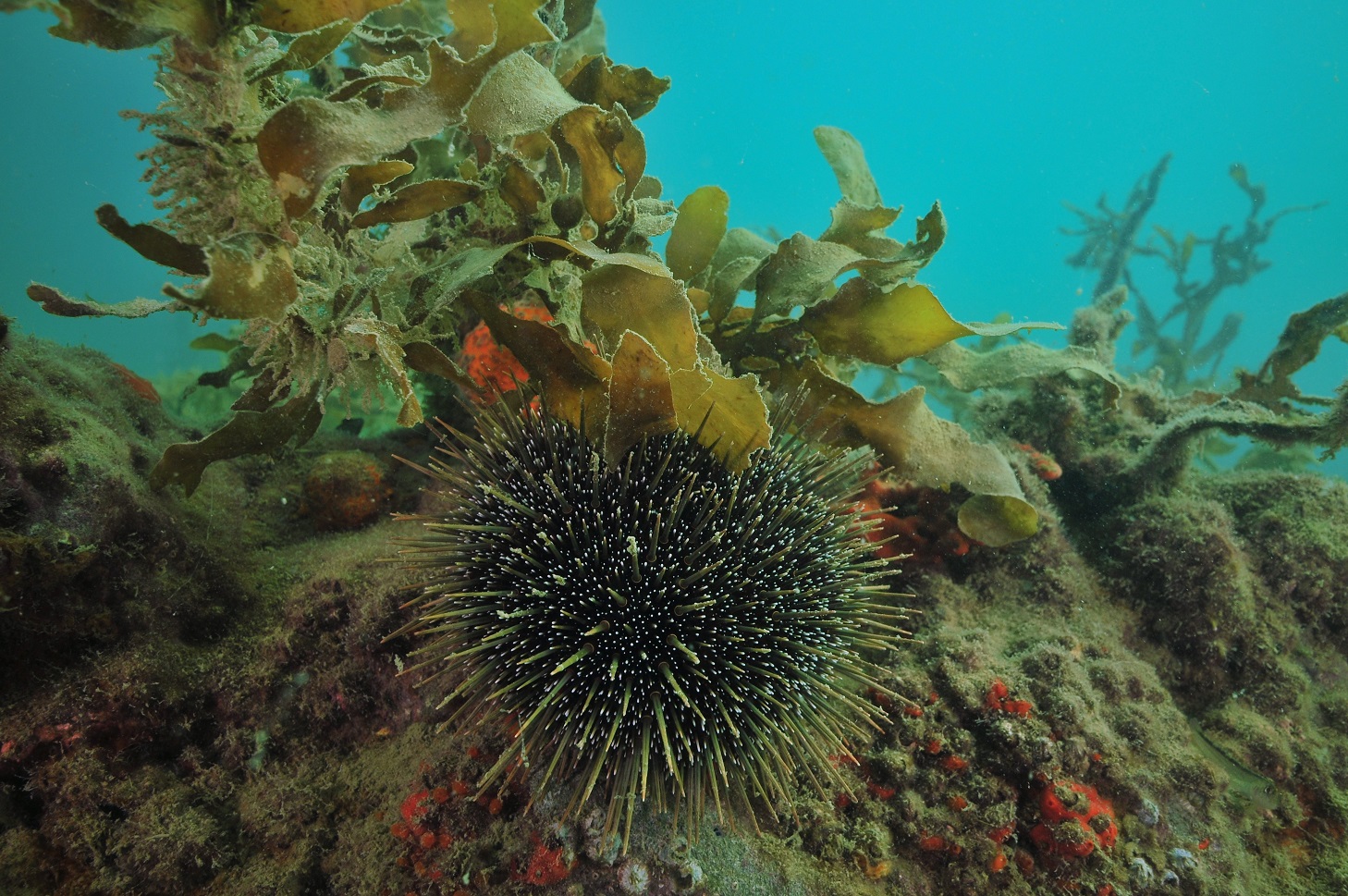

We know that if you damage the bottom of a food chain (by taking away the plants), then the rest of it starves. But what is less obvious is that the top and middle are important too. A clear example is swishing in the waves off the Otago coast.

All around the world, this is a typical cool-water food chain and it’s in trouble. The predators — large fish, crayfish, seals and seabirds — are removed by the planet’s top predator, people. When we collect too many of the predators, then the kelp-eaters take over. In many places, you can see where kelp forests once were — it looks like a logged forest full of stumps. These places are underwater ‘‘barrens’’ where grazers have mown down every single kelp, and all that is left is bare rock.

So, is the solution to kill off some of the grazers? In California, where the hunting of sea otters made the barrens grow, people came up with a solution to bring back the kelp forest. Divers were issued with hammers and told to kill all the urchins they could. In nine hours, two divers can smash more than 10,000 urchins and they still do. But can you put a broken food chain back together with hammers?

Just like a metal chain, or a chain-link necklace, when one piece goes, the whole thing fails. And it is not so easy to repair a food chain. Ecosystem restoration requires a big-picture approach, where we clean up the ocean by addressing what we do on land, so the light can shine on our seaweeds, while also allowing marine grazers and predators to thrive.

A combination of factors is to blame: sedimentation and pollution from the land dims the light and reduces growth, while warming waters and heatwaves cause weakness and stress, so that increasingly strong and frequent storms can rip up kelps. And also, probably, the kelp-eaters are doing their job while we over-fish the predators.

When the kelp forests go, the coastal ecosystem changes. Fish, such as ling and hāpuku, that once lived there are driven further offshore, as are the sea lions that hunt them. Meanwhile, the bare places where kelp used to be are ripe for invasion. While invasive seaweeds may take over, they don’t provide the shelter or the food resource that kelps do.

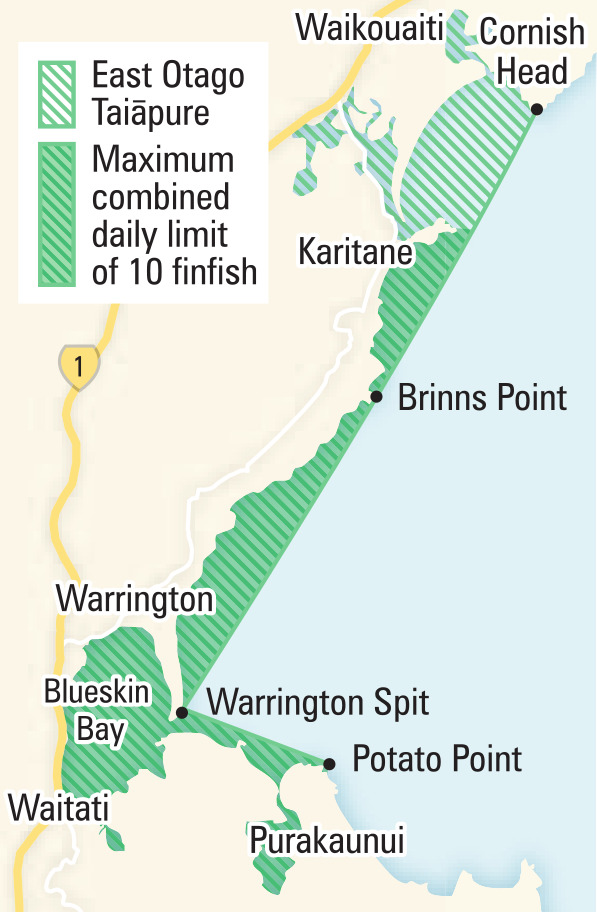

In Karitāne, just north of Dunedin, the local East Otago Taiāpure is working to keep the kelp-forest food chain intact. They are planting on land, to keep sediment out of the local rivers. They have put limits on fishing, and are re-seeding kelps where they used to be. They are hoping that marine heatwaves and storms don’t undo their good work. If they are able to balance the ecosystem, with thriving kelps, grazers and fish, we may be able to see once again the miracle of a functioning food chain without needing to use a hammer.

Eating kina

• Evechinus chloroticus is the green sea urchin or kina, found only in New Zealand. They are often fist-sized but can grow up to the size of a salad plate (about 17cm across).

People have enjoyed the salty foamy taste of kina gonads for a long time. It is said that the roe tastes nicest when the kōwhai are in bloom. We have tried to catch and grow them for export to Asia since 1986, but these efforts have not been very successful. Nevertheless, kina are an important part of kai moana around Aotearoa.

Abby Smith is a professor of marine science at the University of Otago.