Just five years ago the native raptors were considered to be as threatened as yellow-eyed penguins, but they have begun nesting in greater numbers in nearby clear-cut forestry plantations.

Falcons are also believed to be nesting in the city’s fringes.

This autumn New Zealand falcons (karearea) have been reported on social media in Roslyn, Maori Hill, Brockville and Milton.

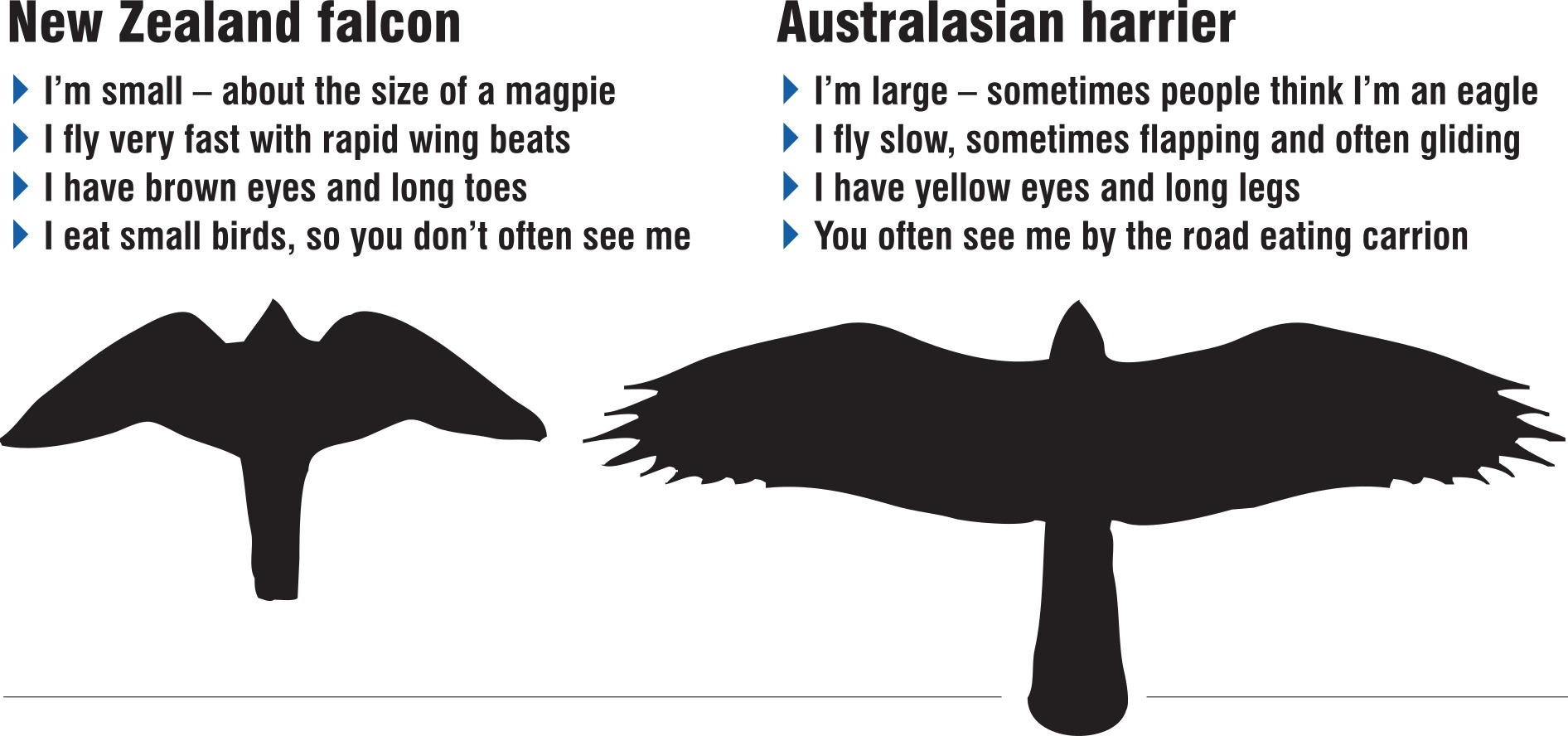

And while there was some confusion as to whether the birds reported were the more common harrier hawk (kahu), Dunedin ornithologist Graham Parker, of Parker Conservation, said he too had received reports of raptors in the city, and they were very likely authentic falcon sightings.

Larger hawks, while similar at first glance, flew in to Dunedin all the time, but were far too wary to land in an urban setting, Mr Parker said.

And while past ornithological surveys of Dunedin’s surrounding areas had turned up no breeding pairs, the birds he studied now lived close by in increasing numbers.

There were at least 50 breeding pairs in forestry blocks in the greater Dunedin area and more still in the fringes of the city, where the urban edge of the city gave way to rural land.

He was hesitant to give out exact nest locations because the birds remained persecuted, he said.

But clear-cut forests provided good habitat for the birds.

Falcons nested on the ground in native tussock grassland, in kanuka forests and on farmland, but rough sheep country that was converted to forestry, and was now being harvested, was providing a good habitat for the predatory birds.

Falcons liked a vantage point when protecting their nests, but they also liked to watch prey.

Clear-cut forestry blocks provided habitat for many small perching birds, often exotic species such as blackbirds and finches, which ate invertebrates, seeds and the grasses that grew up between the felled trees’ stumps.

The falcons, which could reach speeds of 100kmh, used the areas as hunting grounds.

‘‘They are a pursuit predator and that is really open territory for them,’’ Mr Parker said.

And despite all the nests nearby, he did not know of a single nest within the city of Dunedin, Mr Parker said.

The raptors that people were seeing in Dunedin had likely hatched before January, he said.

When falcons were breeding they had a small area, possibly a 1km radius from their nests.

But over winter, their territory could be much larger, and would overlap with other birds, he said.

And juvenile birds would disperse far away from their parents’ territory as they learned to hunt.

In another breeding season, the birds would set up their own territory and try to find a mate.

But male birds in particular would keep on moving until they found a female.

In New Zealand, their survival rates were not known, but international research showed the mortality rate for juvenile birds to be high; about 75% of juvenile falcons did not survive their first year, Mr Parker said.

The Department of Conservation lists the eastern subspecies of New Zealand falcons, such as the raptors found here, as at risk but recovering.

There was a small population that was now increasing after previously declining, the department said.

A spokeswoman said the department had been notified that a falcon was seen in residential Dunedin.

The birds hunted live prey and their diet consisted mainly of birds, she said.