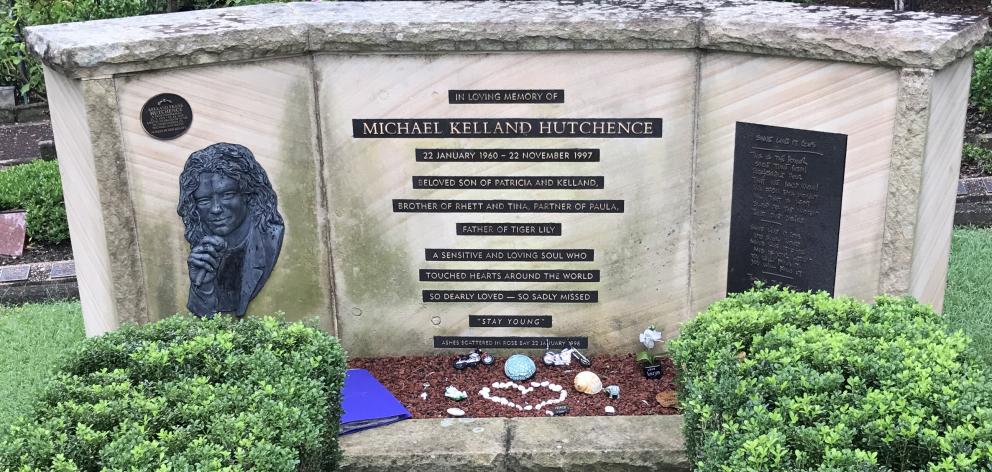

These days I know lots of dead people, but 20 years ago my ghosts were few and elderly. Then, on November 22, 1997, Michael Hutchence died, the first close friend of my age to do so. Grief doesn’t always manifest in tears and pain. For months afterwards, numb and fizzing with a demented energy, I walked into walls and tripped over paving stones. The bruises multiplied as if my body was trying to tell me: "This hurts; this really hurts".

Michael’s death also began to crystallise my unease about fame and our relationship with it.

Eleven weeks earlier, photographers had pursued a car into a tunnel in Paris, then stopped to take pictures of its dead and dying occupants. In the manner of her death, Diana the hunted seemingly left the media nowhere to hide from its culpability. In truth the events enabled a false distinction between mass-market press and the rest of my profession.

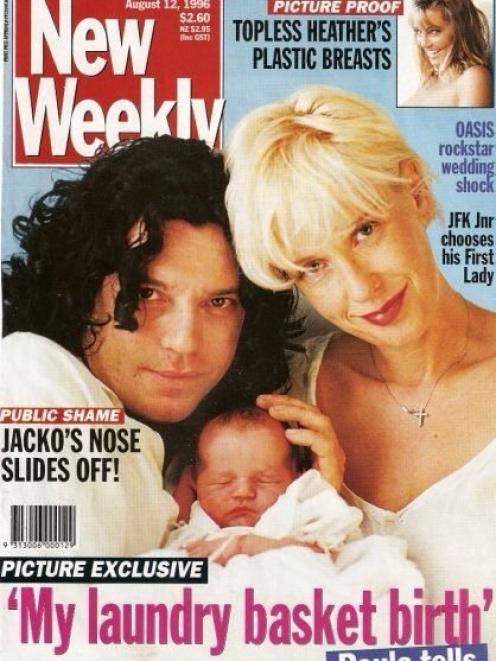

As Michael’s friend, I had direct experience of the excesses of the paparazzi and the tabloids who paid them. I remember trying to drive his Jeep with a photographer draped across the bonnet, firing a flash gun straight into my eyes in his efforts to capture an image of Michael huddled with Paula Yates in the back seat, attempting to shield their baby — their tiny, new baby.

Yet as a journalist — and a consumer of celebrity news — I couldn’t ignore the ways in which print journalists right across the spectrum, from red-top to broadsheet, misrepresented Michael. It wasn’t just about the mixture of sloppiness and invented detail, or even the crass reinforcement of every conceivable stereotype about masculinity and rock stars. Their reports concealed toxic narratives that played out in unexpected ways after Michael’s death and set me wondering about the wider effects of celebrity culture.

Perhaps they thought I shouldn’t care. Our friendship had lasted less than three years, but gained intensity in part because it developed in isolation. We met after he rang my partner Andy Gilland invited him to play guitar on the solo album he was writing. Michael admired Andy’s band, Gang of Four, so much so that he called back a few minutes later to put the question he originally intended but felt too shy to ask: would Andy co-write the album?

Michael’s on-stage flamboyance wasn’t an act — in private he was given to grand gestures and exuberant stunts, on one occasion driving us across rather than around every landscaped roundabout between Nice airport and Roquefort-les-Pins — and singing Come Fly With Me as he did so. Yet he was also soft-spoken and self-effacing.

Andy moved into his French house for the first stage of writing and I would visit at weekends, travelling with Paula. Her relationship with Michael had sparked a frenzy of prurient, tutting editorialising masquerading as reporting. In Britain, paparazzi trailed them everywhere. In France, they found it easier to hide, behind the walls of big estates or in plain sight among other tabloid targets who wouldn’t judge them or sell stories about them.

A fear of intrusion, along with the intrusion itself, shrank their social circle to a small core and then shrank it again. People they regarded as friends did sell stories. We suspected that Paula may have encouraged some of the attention herself, though in the wake of the hacking scandal I wondered if she had actually done so or just fallen victim to an earlier wave of surveillance. Certainly her relationship with the media was far from straightforward. It was a drug that could lift her spirits, but more often punched her in the gut. She was brilliant, hilarious and beautiful, but the woman she saw reflected back at her was a cartoon, an avatar of female folly as drawn by a casually misogynist press. Picture editors lined her up against Michael’s previous lover, the supermodel Helena Christensen, literally anatomising the ways in which Paula, by their standards, fell short. Columnists, often female, excoriated her for daring to believe herself entitled to love — a mother! At her age! With a rock star!

Michael did adore her and she him, although both doubted they were worthy of the other.

"Blocked forever," he emails.

"I did hear I was crying, and screaming: ‘Take me with you’ and ‘I promise I’ll be good’.")

At the same time Paula was enduring the uncertain single-parenting skills of Jess Yates, a depressive TV presenter associated with religious and children’s programming and exiled from both after revelations of his affair with a young actress. Paula discovered in May 1997 that Yates was not her biological father. That distinction belonged to another television personality, Hughie Green.

A media barrage takes its toll on anyone that is its focus. For two people in different ways so fragile, the experience was devastating. The barbs confirmed Paula’s fears about herself and about Michael’s commitment. Michael felt responsible for her anguish. So did I. It wasn’t enough to tell myself that I wasn’t that kind of journalist. Broadsheets ran stories about my friends, too, picked up second-hand from the tabloids and embellished with additional mistakes, as if devoting resources such as fact-checking to the subject forced them to acknowledge their accelerating tabloidisation.

More difficult still, Michael and Paula imagined that I could deploy my professional skills to help them. Michael urged me to write a piece to clear his name after drugs were found in the house he shared with Paula. A great deal about the bust seemed fishy, but I refused.

Paula reproached me for this after Michael killed himself, and I did assist a Sunday Times investigation. Getting closer to the truth didn’t make her feel better. Now she craved one final media untruth to salve her pain. She wanted me to help her build the case that Michael had died in an accident, something she desperately wanted to believe. Yet Michael had called just a few days before he died, crying so hard I couldn’t make out every word, talking of legal battles and the endless, relentless press attention and his own demons.

In any case, I had no faith that the piece Paula wanted me to write would make a difference.

There’s a weasel form of words some journalists favour. They invite their targets to "set the record straight". The expression is at best naive — a single article almost never changes the mood music, especially amid a blizzard of what might now be called "fake news". Moreover those most likely to use the phrase are routinely implicated in the coverage in need of correction. On the day Michael died, a journalist rang me as I tended to Paula to demand I put her on the phone to "set the record straight". The journalist said if she did not, he would write that Michael had killed himself because he’d discovered he was HIV positive. (This was a fiction, as the journalist knew.) On the day Paula died, a newspaper sent me a large bunch of flowers and, hidden in the stems, a letter, inviting me to "set the record straight". If I didn’t give them an interview, they’d speak to people who loved her less and if they got things wrong, well, that would be my fault.

I had no desire to talk about her unravelling, or even to share glimpses into the happier times. I still don’t. As the anniversary of Michael’s death approached, I turned down requests to participate in commemorative films. Yet I chose to write this piece, because I have come to see that what happened to Michael and Paula matters beyond the bounds of friends and family, beyond the private sphere.

There’s a song on Michael’s solo album that drives this point home. The album wasn’t finished when he died so Andy worked to complete it, sitting for hours in the studio, polishing rough mixes and salvaging smaller fragments, and often pinioned by loss as the music gave way to spoken interludes, Michael joking, Michael laughing. The way they had written the songs was that Andy created the instrumentation and then Michael would sing, and they’d usually work out the lyrics and top line together. There were rough mixes of most tracks, songs about Paula, love songs, and other, darker songs. Slide Away, by contrast, had a chorus, but the verses were only sketches. Even so, when Andy listened to it again, he realised how compelling it was. He asked Bono, another close friend of Michael’s, to supply additional vocals to create an extraordinarily lovely duet.

"I just want to slide away," Michael sings.

"And come alive again."

Listening to those words in the immediate wash of grief, this sounded like a desire for resurrection. Now I hear a lament. Michael wanted to slide away, out of the spotlight, out of an intractable situation. If I didn’t understand his impulse for flight and the dehumanising effects of fame back then, subsequent events have brought a brutal clarity.

I remember a woman I liked, who I think liked me and knew I was one of Paula’s best friends, remarking conversationally of an incoherent TV interview Paula gave after Michael died: "Frankly I just wanted to reach through the screen and punch her."

The woman took her cue from the dominant narrative. Even then I still assumed that narrative to be dictated by mass-market newspapers, treating OK! magazine’s presence at my wedding to Andy as an amusing adjunct to the entertainment. Days before our first anniversary, I switched on the TV to see Paula’s body carried out of her house. The coverage of her death across all types of media, untainted by facts or insight, finally dispelled any notion of a benign press or a quality press where the famous are concerned. Later, we watched helplessly as a similar lazy consensus damned Paula’s daughter Peaches as spoiled and indulged, a judgement as far from the truth of her short life as it’s possible to imagine.

Peaches lived online and died in the digital era. It was easier to advocate for free speech, as I still do, before so many exercised it so avidly. Issues of privacy and public interest are becoming increasingly intricate and journalism — the kind that invests in establishing facts, or even recognises the value of doing so — is endangered, in turn endangering democracy. Celebrity is rapid-cycling and more double-edged than ever. The transaction confers certain privileges and responsibilities while apparently stripping the recipient of the basic right to be recognised as a person rather than a cipher.

The famous are by no means the only ones to suffer as a result. If we accept the idea that individuals in the public eye are less than human, how should we insist on the humanity of those without names or profile? They too easily become migrant tides, aliens, collateral, unidentified and unidentified with. In depreciating celebrities while commodifying celebrity, we risk undervaluing everyone.

— Guardian News and Media