Seeing a jewelled gecko in the wild was the beginning of what Carey Knox identifies as a complete obsession.

It was 2008, and Carey was studying wildlife management at the University of Otago.

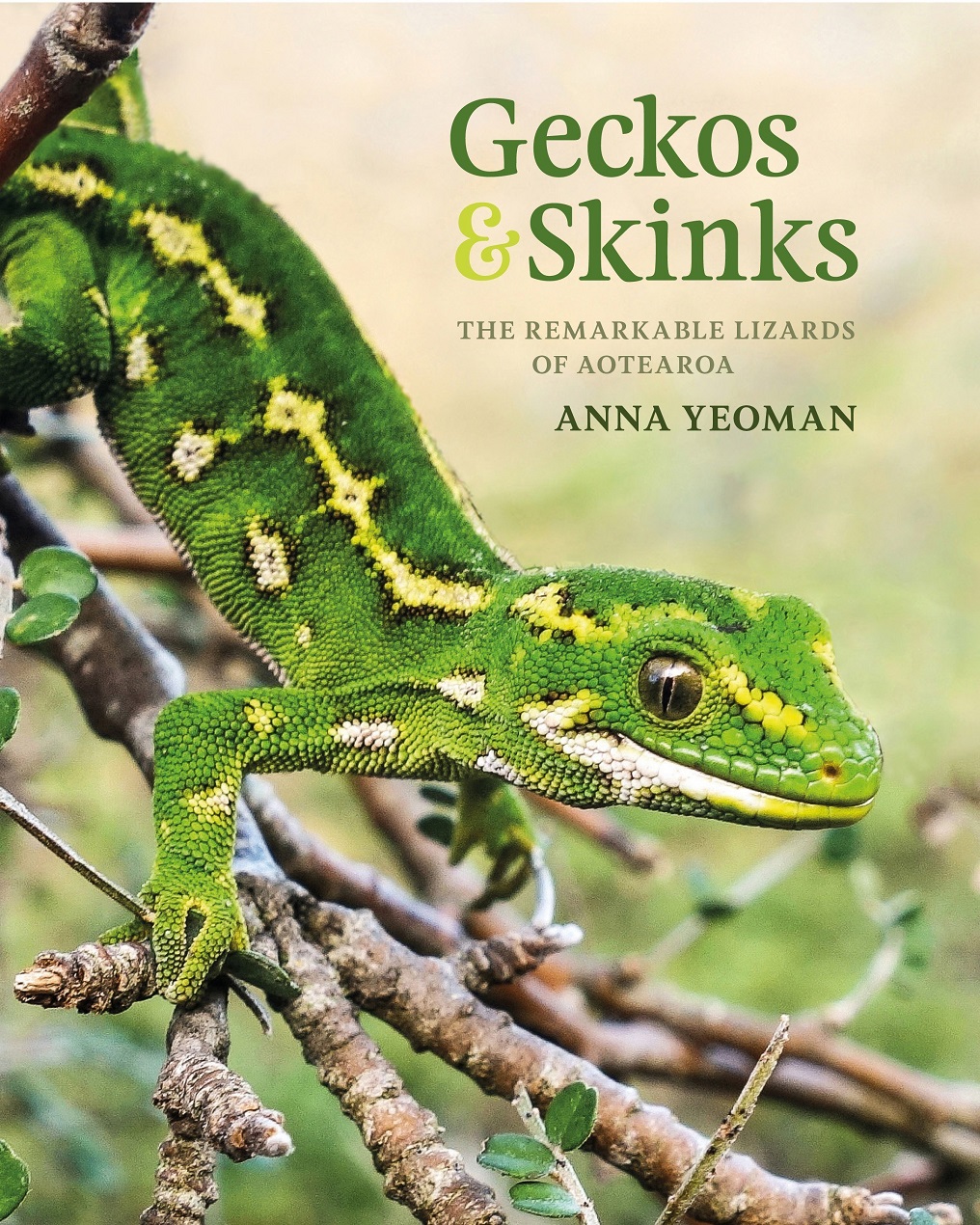

On the bright November day when he found his first jewelled gecko emerald green with white diamonds scattered across its back and round, shining eyes he couldn’t believe no-one had ever told him about them before.

He started to spend hours on Otago Peninsula finding, photographing and cataloguing the animals. While the work formed part of his masters research, he found himself easily exceeding the fieldwork requirements. He clocked up 100 days and then some, drawn out at all hours of the day and night by the allure of the geckos.

The timing of his interest would prove serendipitous.

Jewelled geckos are eye-catching, beautiful, exquisite to a degree that can be mesmerising.

They’re the southernmost of New Zealand’s nine species of green gecko, living in scattered populations from Foveaux Strait to Canterbury. Their typical patterning gives them both their scientific and common names: Naultinus gemmeus, the jewelled gecko. Yet on closer investigation, their colour patterning is widely varied.

In the deep south, on the islands in Foveaux Strait, jewelled geckos are plain green with no markings.

In the hills of inland Otago they’re a particularly luminous green with lime diamonds.

In coastal Otago, jewelled geckos have diamonds, or sometimes stripes, of yellow or white. On Banks Peninsula the diversity is even greater; the females there are green, the males are grey or brown, and both sexes can have diamonds or stripes of anything from white to yellow, beige or highlighter green. When jewelled geckos open their mouths they reveal further variation; in Otago, they have a deep blue mouth lining with a pink-blackish tongue, and a mauve-pink mouth with an orangey tongue in Canterbury.

Yet there’s a downside to their striking colouration. In Christchurch in 2011, three men were arrested trying to leave the country with 16 jewelled geckos in plastic pipes in a backpack.

New Zealand’s green geckos are desirable pets on the international black market, targeted because they’re the colourful exception to the majority of the worlds geckos, which are brown or grey. They’re also active by day, where most of the world’s geckos are nocturnal.

The men were arrested, and the geckos were returned to the Department of Conservation (Doc) office in Dunedin.

From his database of images, he was able to identify 11 of the 16 geckos. He had records of the sites the individuals came from, sometimes down to the exact tree or shrub. The markings on every jewelled gecko are distinctive, unique like human fingerprints, so photographs of their backs can be used to reliably identify individuals. Even jewelled geckos photographed as babies can be recognised years later.

Although the markings expand as the lizard grows, and some colours may deepen, the shape and alignment of the patterns remains the same throughout their life.

Carey helped Doc return the stolen jewelled geckos to their home patches of bush. Jewelled geckos live in native shrubs and trees, most often in coprosma, kānuka, mānuka, tōtara and matagouri. They have long tails, longer than their bodies, which they use like an extra limb as they climb and swing through the branches. On calm sunny days, they forage for nectar and berries or bask in the sun. They catch insects that come close.

Sometimes they emerge on mild nights, particularly between dusk and midnight, and will catch the moths attracted to the native shrubs. Their intricate patterns, likened to those of a Persian rug, camouflage them exceptionally well, and in the small-leafed shrubs they can be near-invisible.

Learning to spot them is an art, and a game of patient practice.

Several major news outlets covered the story of the stolen jewelled geckos being returned to their homes. It was a wonderful story, celebrating a welcome win for wildlife protection. Yet during the year that followed, the jewelled gecko population at the site plummeted. About a third of the 100 or so geckos that lived there disappeared. The site was being targeted by other poachers.

The threat of poaching caused anxiety for landowners who had jewelled geckos living on their properties, as well as for herpetologists, Doc staff and community groups like Save the Otago Peninsula (STOP).

The anxiety threatened to morph into paranoia.

From the deck of his mother’s house, Carey could see one of the jewelled gecko sites and when he visited her, he found himself constantly picking up binoculars, scouring the gecko site to check for suspicious vehicles.

One of the cruellest aspects of wildlife smuggling is the impossible dilemma it creates between promoting an animal in order to raise conservation interest, or hiding its presence in the hope of foiling poachers.

Decisions are fraught. Can school children on Otago Peninsula learn about and visit the taonga on their back doorstep, or does the risk of information leaking on social media mean they cannot?

There was particular concern about the jewelled geckos that still lived at the targeted site.

After considerable deliberation, Doc decided to move as many as possible from there into the safety of Orokonui Ecosanctuary on the other side of Otago Harbour. The decision to translocate animals is never made lightly because the stress it causes the uplifted animals makes a positive outcome far from guaranteed. Yet in this case, it seemed the best option.

Herpetologist Marieke Lettink has worked with jewelled geckos on Banks Peninsula since 2005 and part of her job involves writing impact reports to inform the sentencing of poachers. She found herself getting increasingly angry about the situation.

One suggestion that continued to surface was that to combat poaching, jewelled geckos could be bred in captivity and offered for sale to undercut the illegal market. The strategy had been successful for several species overseas, including the New Caledonian crested gecko.

Tired of hearing the suggestion thrown around, Marieke did the maths to show why this was infeasible with New Zealand lizards. If you start with 20 newborn crested geckos, which give birth to many young in quick succession, in 10 years they’ll have bred 62 trillion crested geckos. However, jewelled geckos don’t mature until they’re 3 or 4 years old and have just two babies per year.

This means 20 newborn jewelled geckos will, after 10 years, have bred 140 jewelled geckos. It wasn’t going to work.

In 2012 on Banks Peninsula, a German national was arrested with four jewelled geckos in his campervan, tucked into pairs of socks. The poacher had targeted a gully referenced in a report by a New Zealand wildlife ecologist.

Marieke trusted the ecologist with the GPS co-ordinates of the site and was sickened to realise the information had somehow made it into the wrong hands.

The poacher spent less than four months in jail, his sentence shortened from the maximum time of six months on account of making an early guilty plea and being an animal-lover because he’d worked at a cat and dog sanctuary in Germany. Marieke, along with Alison Cree, Carey and a number of other New Zealand herpetologists, pushed for the smuggling penalties to be tightened. The judge made the same recommendation.

The maximum penalty is now five years in prison and a $200,000 fine, and there is an international agreement against possessing any New Zealand green gecko overseas.

A decade on, it appears the tighter restrictions are making a difference. While some poaching still occurs, the intensity has eased, and Carey and Marieke no longer feel the constant anxiety they once did.

Herpetologists are also highly aware that habitat loss and introduced predators are taking many times more lizards than poachers ever will, and most of their work focuses on these threats. On Banks Peninsula, Marieke has worked with over 50 landowners, surveying their land for jewelled geckos and sharing recommendations for how to best protect the lizards. When she can, she takes the landowners to where the geckos live and lets them find one for themselves, hoping the captivating geckos will work their own magic.

The key recommendation she makes is that areas of native shrubland be left as they are, not cleared or burnt.

Some landowners have placed covenants on areas of bush.

In 2012 an opportunity arose for Marieke to embark on a research project comparing the survival of jewelled geckos at two different sites on Banks Peninsula: one without predator control, and one where predator control was just beginning.

On six fine days every spring and autumn, Marieke walked transect lines across the two sites, searching for jewelled geckos. Female geckos with wide bellies soaked up the sun on the sheltered side of the shrubs, taking in the energy required to grow their offspring. Young males explored for new territory.

Hardest to spot were the baby geckos. At six centimetres long, thin as twigs and perfectly patterned with tiny diamonds, they scrambled and slithered their way through the latticed branches learning to find nectar, fruit and insects for themselves.

Marieke recorded each gecko she found.

For the first two years of Marieke's research, jewelled gecko numbers in the predator-controlled site increased.

Then the increase slowed, and numbers even looked to drop slightly. By 2022, 10 years into the study, the bad news was undeniable. While the jewelled gecko numbers at the site where there was no predator control remained steady, at the predator-controlled site they were declining.

It was strange, to say the least.

The desired outcome had not been achieved for unknown reasons, Marieke wrote in her report. She and her colleagues puzzled over what these reasons could possibly be.

By definition, ecosystems are connected entities. When one part is changed, other parts will respond, sometimes in surprising ways. One possible explanation of the findings was that removing mammal predators could have led to an increase in birds like blackbirds, starlings and kotare/kingfishers, which kill lizards.

More research was needed.

However with a species that breeds as slowly as the jewelled gecko, the effects of any ecosystem change are only seen after several years, making gecko research a very slow game.

Another counter-intuitive relationship had emerged in Carey’s research in 2010.

During his early searches for jewelled geckos on Otago Peninsula, Carey had gained the impression that some of the best gecko populations were on grazed farmland. He decided to investigate the question for his masters research, and found that jewelled gecko numbers were significantly higher in grazed coprosma shrubland than in non-grazed. It appeared that where there was no stock keeping down the seeding grasses around the coprosma bushes, mouse numbers soared.

Where there were plenty of mice to eat, numbers of other introduced predators increased too, and then the geckos suffered.

These rather surprising results have shaped the recommendations Carey and Marieke make to landowners.

While many people have a desire to do something to help the jewelled geckos on their property, the data suggests that at present it might be better to let sleeping dogs (or geckos) lie.

Jewelled geckos probably evolved in mosaics of open woodland shaped by the grazing and trampling of moa.

While cattle are too rough, some light sheep grazing seems tolerable, and could even be beneficial to geckos in coprosma shrubland, at least until another way is found to keep mouse numbers down. In the long term however, the ideal action is to let the native forest regenerate.

The predator control question is even harder. It’s certainly true that removing all introduced pests benefits native ecosystems, but removing just some of the pests can lead to perverse outcomes. It requires very careful monitoring.

There’s still a lot to learn, and Marieke and her colleagues continue passionately seeking to understand what it will take for green gecko populations to thrive in the New Zealand wilds again.

Thankfully, in the meantime the jewelled gecko populations on both Otago and Banks Peninsula look to be holding on.

Carey’s database of jewelled gecko ID photographs now contains over 3000 individuals; Marieke's is similar.

The 42 jewelled geckos translocated to Orokonui Ecosanctuary, some after their rough side-trip to Christchurch Airport, are doing all right.

The jewelled gecko seems to have a good degree of resilience.

After two decades and thousands of encounters with the exquisitely patterned animals, Marieke and Carey are still thrilled by every single one.

THE BOOK

Geckos & Skinks: The remarkable lizards of Aotearoa by Anna Yeoman Published by Potton & Burton; $59.99 RRP, out now