Writing under the name ‘‘Pakeha’’, Thomson’s detailed accounts of botany, vegetation clearance rates and suburban development are regarded as among the best contemporary records of Dunedin.

Today we find him in the far south contemplating a trek to Orepuki.

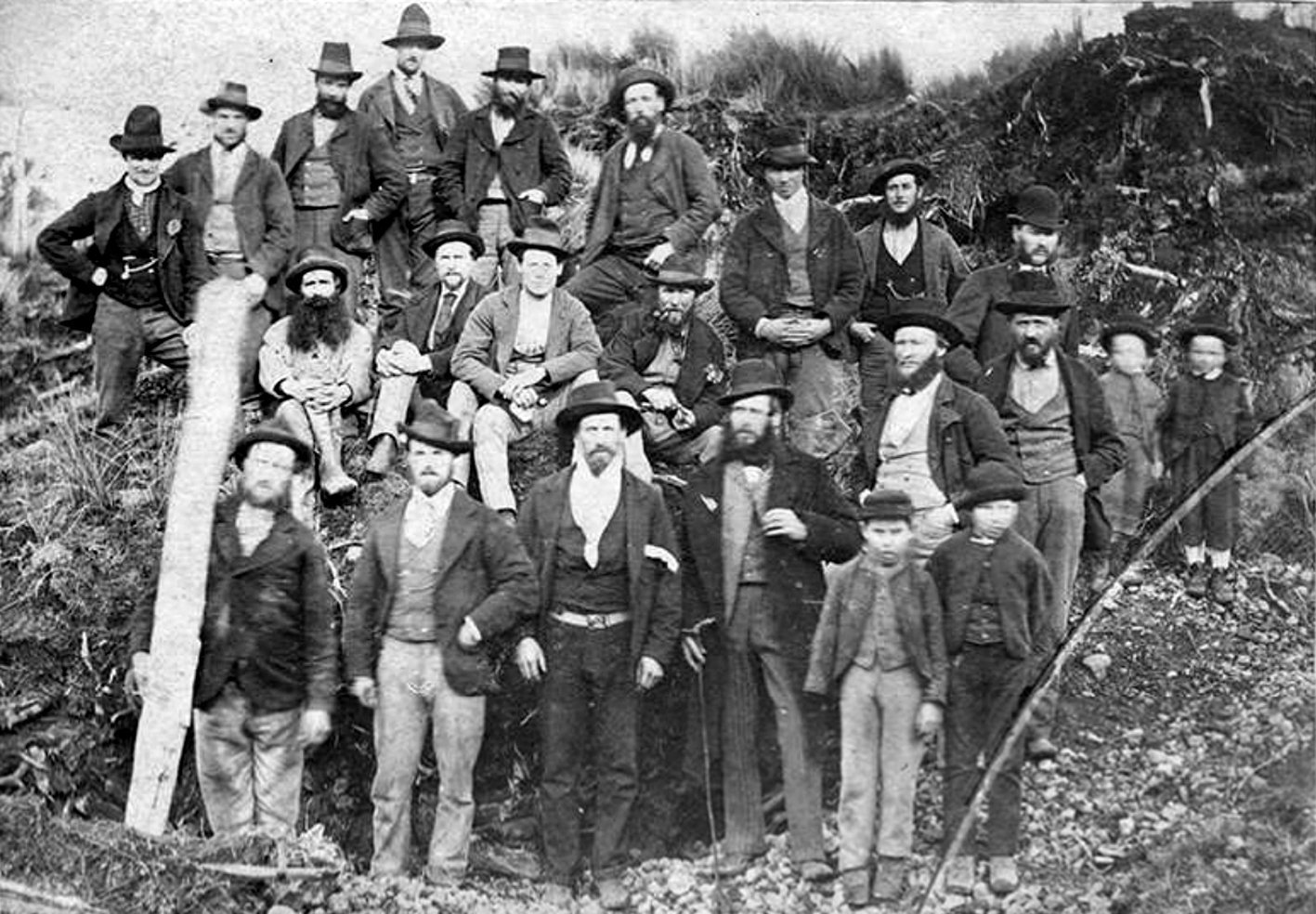

My intention was to make for Orepuki from Riverton, but I had heard so much of the dreadful track that existed between the two places, that it made me rather timorous about starting alone. However, on returning to Riverton that afternoon, I found a large party of miners had come from Orepuki, and brought a sick man with them for medical assistance. This was a really noble undertaking. No fewer than 38 of these hardy fellows (all the men that could be spared) had volunteered to carry their mate on a stretcher, over 25miles of what must be considered the very worst track in the Colony. It reflects infinite credit on their humanity. It is not the first time they have done so either. I had an introductory letter to one of them, and almost the first man met in the street was the gentleman. So arrangements were made for my accompanying the party back in the morning. We were to start at 9, but it was 10 before we were fairly on the road.

The first eight miles lay along the famous Western Railway, about which so much was said and written. A large amount of work has been done on this line, and it is melancholy to see the cuttings and fittings half-finished, culverts built, planking, barrows, waggons, dobbins, etc, lying about, going fast to decay. The work must have been stopped in a hurry, for there were waggons and barrows standing about filled or half-filled, run out to the bank and not emptied, and so on, as if some magician had cast a spell over the whole work, which, I suppose, in one sense, was the case.

The walking over the track varied very much - sometimes it was very good, lying on a level railway embankment, which would end in a steep wet gully; and then the track would wind through numberless stumps for a long way, until a bit more of the formation was met. This was repeated again and again, the whole distance from Orepuki to Riverton being through heavy bush. The only opening the whole way is where the line crosses a curious piece of swamp, over which a sort of corduroy track of manuka scrub has been formed. Beyond the swamp a short way the clear line ends, and there is only a survey line for the rest. On this line nothing has been done, beyond making the space enough for the surveyors to see, and as it is carried straight through, over everything that came in the way, travelling is about as difficult as it could possibly be.

One while we would be pushing through, thick underwood, knocking our legs against stumps and branches; then climbing up and down the sides of a steep gully, with obstructions of every sort in the way; or climbing under or over the trunks of fallen trees of all sizes, which were slippery in the extreme. All this was through a dense bush, in which we could rarely see the sun. The day was warm, and the fatigue told rapidly on me, but there was nothing for it but to hold on. I did not believe in turning back.

In the heart of the bush, about 10 or 12 miles from Riverton, there is a small digging township called Roundhill, in the neighbourhood of which there are some very good claims. The miners have made a small clearing here, erected huts, and made small gardens. To one of these huts we made our way on arriving at the clearing, and were most hospitably received by its owner, named O’Brien. I don’t think I ever drank tea out of a pannikin with so much relish. Between the heat and the fatigue I felt nearly dead beat, but the rest and the drink of tea soon set me up again. Some dinner was set before us, and though the accommodation was rather limited for such a large party, we made the most of it, as we were made most welcome to the very best the hut contained.

After resting here for about an hour, the leaders of the party set us all agoing again. Our way was changed, for although the survey line is continued through to Orepuki, it was judged too difficult, and so the track to the Paihi Flat was adopted instead. This was a very great improvement on the other line, having been cleared about four feet wide for about two miles, and we sped over this bit quite pleasantly. The remainder of the track, however, is yet in its original state, and is very bad, muddy in the extreme, encumbered with all sorts of obstructions, and anything but direct. None of the party were sorry when the welcome daylight appeared, and we emerged hot and thirsty on the Paihi Flat.

About a quarter of a mile further on the track crosses a creek, and here a rest was had, while one of the party who had on thigh boots got down to the water and handed up drinks to the rest. There were yet a few miles to go before reaching Orepuki, including the crossing of another patch of outlying forest, so after a little delay all were on the move again. The ground was generally wet and swampy until the level open ground near the township was gained, when the party gradually dispersed to their several habitations.

I was very glad when the Shamrock Hotel at last came in sight, and was surprised to see a substantial well constructed house in such an out-of-the-way place as Orepuki. Everything was very comfortable, and fatigue was soon forgotten over the details of a well-spread table. In the morning everything looked smiling. The sun was shining, and the hills and scenery around were grand. I went out on the Flat a short way, and had a good look at the surroundings. Away to the westward lay the sea, and beyond it were a range of the grandest looking mountains I had seen - the Princess Mountains - running up into peaks of all shapes, about 5000 feet high.

Nearer hand was the broad valley of the Waiau, but the river itself was not visible. To my right was the Longwood Range, covered with timber to the top. On the other side the view was bounded by the bush, while round the township lay the Flat.

After breakfast, I started on a round of the principal workings, which are mostly in the bush, at the base of the Longwood Range, on a terrace. The system adopted is the hydraulic, and the gold is very fine, and distributed thinly through a bed of gravel, lying at a varying depth from the surface, some of the claims being 40 to 50 feet deep. A tail race has been carried up from the sea at great expense, and the head races are brought in from the Longwood and other ranges, and from the Waimeamea, a considerable distance off. About 120 men are employed in the various claims, and the yield for the year is something over 4000 ounces. There is a bed of capital lignite, about 18 feet thick, and of unknown extent, which was discovered in a race; and near it there is a thick seam of kerosene shale, so full of oil that a bit of it being held over a lighted match it takes fire and burns readily with a yellow flame and black smoke.

Of course, the district is hardly known yet in a mineral sense, as gold is the only object of search. And until roads are formed to the locality, the mineral wealth of the district will remain undeveloped. A road, or the completion of the railway through the bush to Riverton, would give an immense impetus to industry of every sort at Orepuki, while the immense extent of timber only wants an outlet to be available to the rest of the Colony. The whole of the country from the Waiau to Jacobs River is a forest, abounding with valuable timber of every kind.

The next day was spent in making the ascent of the Longwood, a high broad range running away to the north from the coast, and parallel to the valley of the Waiau. The track led through among the workings, along the sides of races and claims, until the base of the mountain was gained, when the line of an old race, the water of which is now diverted to a newer line, was adopted for a long distance. There was a multiplicity of tracks at first, and my guide, Mr Creasey, got a little doubtful of the one we were following, and one of the miners in a big claim kindly left his work and put us on the proper path to the top of the hills. The bush was very thick, and we could hardly see the sun, but at times we had a glimpse, when our direction was noted as north easterly.

For a time we were continually crossing races, or old workings, dams, etc, but gradually all these were left behind, and the only sign of mining was the old race. This we followed for a long distance, gradually rising, and the mixed pine bush of the lower terraces got mixed with iron-wood; then the pines became scarce and the trees were nearly all beech. As we rose, the track got steeper, and the ground was pretty rough, but still the walking was by no means disagreeable, and we got on rapidly. At about two-thirds of the way up we came to an old hut, where the race-cutters used to live, and here we camped, lighted a big fire, and ‘‘slung’’ the billy. After a good meal and a good rest we started to the summit, and soon began to notice the trees getting stunted in growth, and a number of shrubs not seen below were growing about.

At last we emerged from the trees into a small mossy glade, and here I had the pleasure of collecting some plants I had never seen before. The whole surface of the hill above the bush was covered by a deep growth of mosses, with small patches of veronica and other shrubs, interspersed with large blocks of grey granite sticking up here and there. One curious thing was the presence of deep pools of water, little lakes, in the flat surface. I went to the edge of one and put down my stick but there was no bottom.

A little to the left of where we emerged from the trees there was a little rocky peak, and we made our way there, and got on the top in order to have an uninterrupted view all round, and a most magnificent prospect lay before us. To the east we could see the whole Province of Southland, right across to the mills beyond the Mataura, and the coast line at intervals from the Bluff to a long way to the west of Waiau, which river was visible in several long stretches, including the long sand-bar which divides the river from the ocean. The mountains to the west and north, however, were very indistinct, and soon were invisible altogether, as a thick fog settled on them.

Riverton and the estuary of the Jacobs, with the Purakino, were apparently quite near, with all the country around for a long way. While we were enjoying the fine prospect, the fog we had seen on the western hills suddenly enveloped us and a smart shower of rain fell, which drove us to the lee of some big rocks for shelter, where we kindled a fire, there being plenty of dry sticks lying about. The shower did not last long, and we spent a very pleasant time wandering about on the hill top collecting mosses and ferns. The fog still hung on the hills, but after a little we got a good view of the Pahia, Orepuki, the Strait, Stewart’s Island, etc.

The top of the Longwood was a most interesting place, and had my time permitted I could have spent a couple of days on it instead of an hour and a-half, which was all that could be spared. We got back to the top of the track, and after getting a few of all the plants and ferns we thought interesting, packed up and started down again, reaching our camping place at the old hut in time to find the fire still burning. The billy was again slung, and after a feed and a good rest, the remainder of the long road was got over in good time, without any other disagreeability than what was caused by a heavy shower, which came on when near the foot of the hill. The hotel at Orepuki was gained shortly after 7 o’clock.

Next day was devoted to the return to Riverton. I was to be accompanied part of the way by my worthy guide, Mr Creasey, who had some business to arrange at Wakapatu, and we were to have gone so far on horseback, but when it came to starting the animals were not to be found, so we had to take the means of locomotion provided for us naturally. The first part of the way was pleasant enough, across the undulating open ground near the township for a mile or two.

But after passing through about half-a-mile of bush, and getting down upon the Paihi Flat, then the trouble began. We took the precaution while passing some flax to tie the legs of our trousers tight round the ankles, and it was well we did so, for we had not gone far on the Paihi where the mud was over the boots. It was a long and tiresome journey getting over these five miles of swamp, but it was done, though the change to the bush on the other side was only one from thin mud to thick mud. If anything the bush was worse than the flat, which here and there had some places which were firm; but the bush was simply detestable, and the walking turned to splashing through mud holes. I was lucky enough to escape plumbing any very deep place, but managed to get through without going over the knee.

At Wakapatu, we had a good rest, and a dinner of wild pork. Here my friend and I parted: he to take a bee line back to Orepuki, I to take the beaches and bush to Riverton, where I arrived shortly after 7 o’clock, pretty well tired out, the distance being nearly 25 miles over the worst track in the Colony without exception. It is high time that something was done by the authorities to make a passable track from Riverton to Orepuki. Very little would please the miners, who are willing to help as far as they are able. But a simple foot track, with light bridge - a couple of sticks and a handrail over the creeks, could be easily and cheaply made, and would be a great boon to the population scattered about Round Hill and Orepuki, enabling them to get provisions and stores of all sorts carried through at a much lower rate than is now charged.

I spent the next day about Riverton and its neighbourhood, taking a look at the sunken steamer Express and the operations going on for its recovery, a stroll round the Maori Kaik, and so on. The position of the Express is causing some alterations of the banks in the harbour, and the Wanganui, in trying to get out ran on the bank and lost a couple of days there getting off again. Next afternoon the coach took me back to Invercargill, through a pelting shower of rain the whole way, which was the first bad weather experienced; and the next morning at 6.30 I was in the train to Mataura, from which I coached to Balclutha, arriving home again at 9.30, thoroughly well pleased with my rambles in the southern district of the Province.

PAKEHA. April, 1877.

• Original spellings have been retained. A collection of Peter Thomson’s published articles has been compiled by his great-granddaughter, Mary Skipworth, and can be viewed at genealogy.ianskipworth.com/pdf/peterthomson.pdf