Macraes Flat

Past and present intertwine in Macraes: from the gold mines of the 1880s to New Zealand’s largest modern gold mine; from the stone solidity of Stanley’s Hotel, a hub for the present community of 500, to rusting remains of the 19th century stamping battery; from the impressive 12m wingspan sculpture of the now extinct Haast’s Eagle lunging out of silver tussock, to the mudbrick miners’ cottages of early days - this is an area that lives alongside its past.

You see the contrast between the struggles of early days, and the benefits that have come from the contemporary mining operation.

John Macrae settled here around 1859 to farm, only to be flooded by diggers out to make a quick fortune when gold was discovered in 1864. Unlike many goldfields which vanished after a short burst of glory, one mine - Golden Point - continued working until abandoned in the 1950s. Located in a deep gully, the mine has an authentic working battery which is still fired up several times a year.

Along with abandoned rusting machinery, there is the mine manager’s house and several mudbrick miners’ cottages.

The present-day mining operation, OceanaGold, is vastly different. It is New Zealand’s largest active gold mine, with a large-scale opencast mine which began in 1990 and a newer underground mine opened in 2008, producing over 50% of NZ’s gold. It makes a spectacular sight, to see the huge mine in operation, the complete opposite of the tiny Golden Point mine.

There is more than gold! History goes well back to pre-European times and early archaeological sites have been found on the inland exploration route of the first Polynesian settlers passing through this area.

Today it is dominated by tussock and farmland but was once covered in shrublands, podocarp forest and native grasses. Its fauna is rich, too - seven species of lizard and skink classified as threatened, and on the rocky bluffs and outcrops there are some 53 species of bird, including terns, gulls, bitterns and banded dotterels, along with the rare and endangered kārearea, the New Zealand falcon.

From Palmerston on SH1 travel inland for 15km on SH85. Turn left on Macraes Rd and continue 19km to Macraes.

Hyde

Remote, even by Central Otago standards, Hyde was originally known by the very practical name of Eight Mile as it was eight miles from the Hamilton goldfields. Gold miners were not easily deterred by mere distance so when gold was discovered here in 1863, within a year, a town of 1200 had sprung up, with about another 1500 miners working smaller fields in the district.

The isolation gave the town a strong sense of identity and self-reliance and in December 1864 the Otago Witness newspaper described Hyde as "remarkably lively, and seems to be in a state of excitement and gaiety. Horse racing, balls and suppers, almost every evening, make the town by far the more spirited place round about".

Now a familiar story, the easy gold was quickly worked out and the miners turned to the more expensive sluicing, but even that couldn’t hold the inevitable at bay. Miners drifted off to easy workings elsewhere in Otago or the West Coast, and by the end of 1865 Hyde’s population had dropped to less than 150 people. Even so, the town still had several stores, a post office and two hotels.

Unlike other parts of Central Otago, the Taieri River Valley attracted farmers and the early, very large sheep runs were broken up into much smaller holdings.

A bridge over the Taieri River opened in 1879 and, with the arrival of a railway in 1894, Hyde was no longer so isolated. While the heady gold days were long gone, the town still had good facilities including a school, a hall and a new Catholic church opened 1894. The Presbyterians had to wait until 1927 for their new church.

On June 4, 1943, one of New Zealand’s worst rail disasters occurred near Hyde when the daily passenger train failed to take a bend at Straw Cutting and all the passenger carriages left the tracks.

The combination of the accident in a deep cutting and the distance from emergency services made rescue difficult. Twenty-one people died and 47 were injured.

While gold mining was now a dream, mining continued in the district, but this was for scheelite, schist rock for buildings, silica sand for glass and even high-quality clay for pottery works.

In 1990 the railway line closed and in 1999 the school, opened in 1879 and now down to just four pupils, also closed.

The opening of the popular Otago Central Rail Trail gave Hyde a much-needed lift and today the town has about 20 residents and a small number of historical buildings.

From Ranfurly travel 15km east on SH85. Turn into SH87 and drive 20km to Hyde.

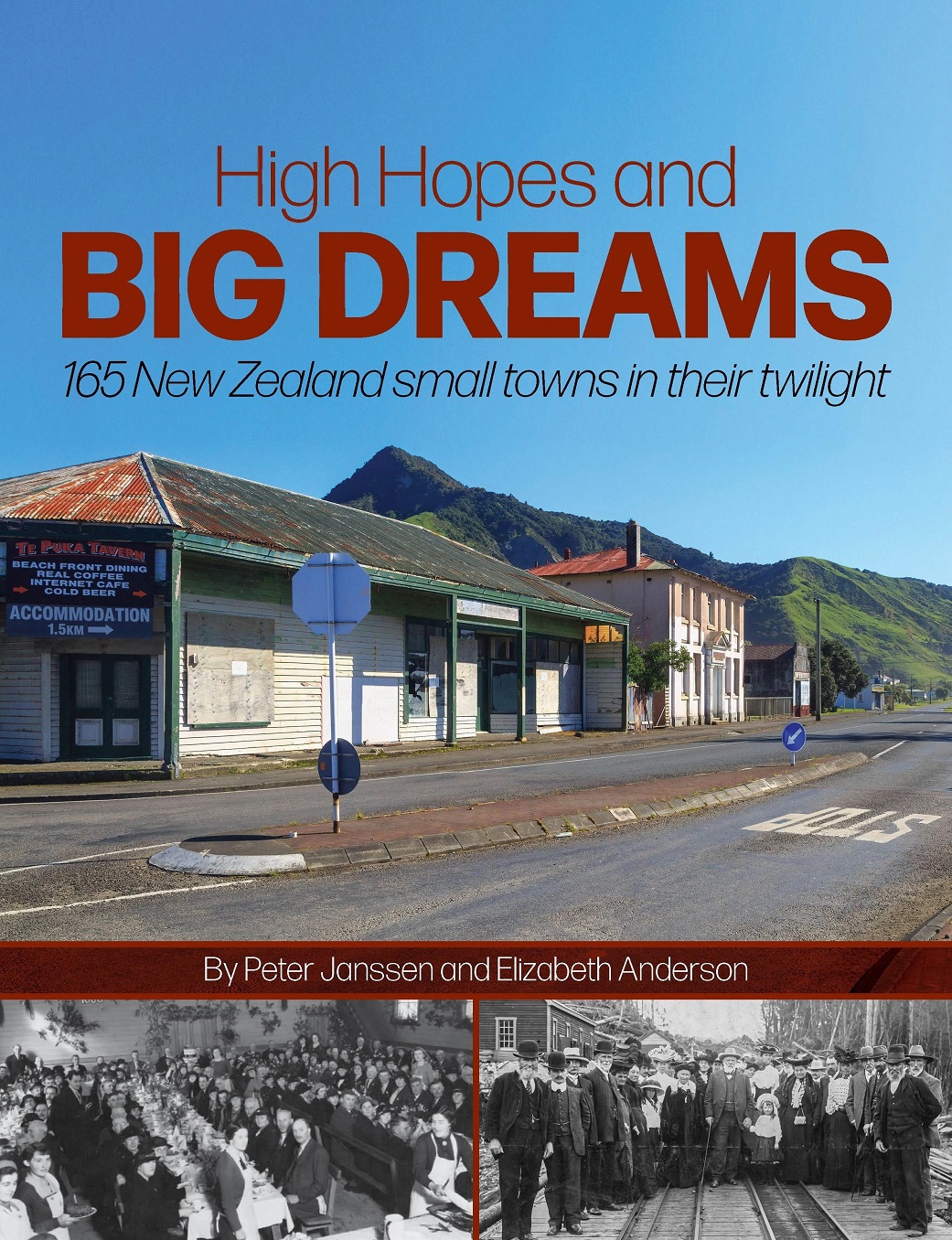

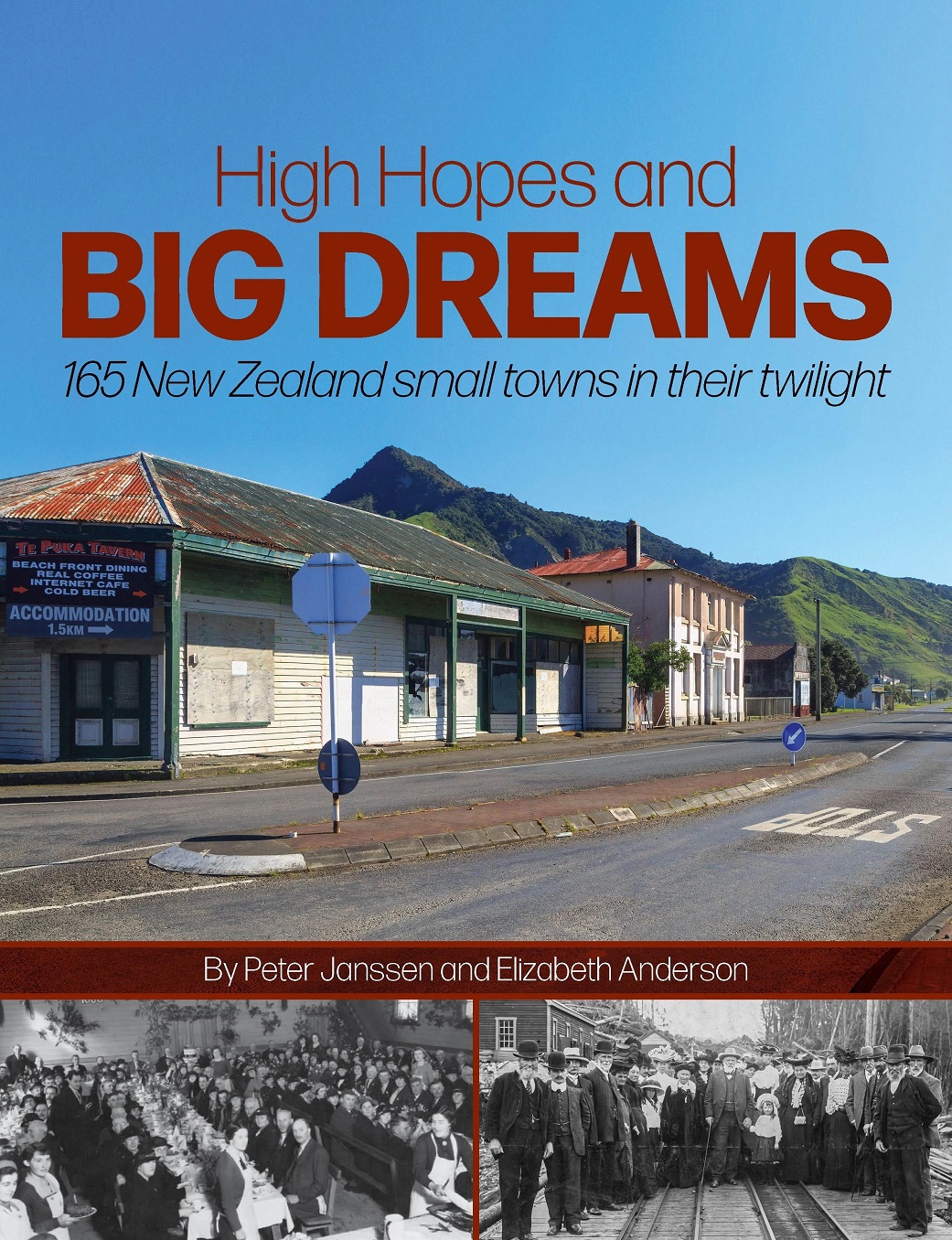

The book

The book

High Hopes and Big Dreams: 165 New Zealand small towns in their twilight, by Peter Janssen and Elizabeth Anderson, (White Cloud Books from Upstart Press, RRP $49.99)