White spent the first part of his career as New Zealand’s best known and highest-paid press photographer, working for The New Zealand Herald and a range of other publications.

His assignments were extensive and highly varied, from the tops of mountains to the pits of mines. As he developed his craft, the potential of flight became very enticing to him, with its new perspective of New Zealand’s development and landscape.

White took to the skies for his first aerial photo (1921) less than two decades after the Wright brothers’ first flight.

He was a young man with glass plates in his bag, ready to push early cameras to their performance frontier.

While hard to fully appreciate now, the breakthrough of aerial photography was a big deal.

Farmers were so awestruck by elevation that they couldn’t help but aerially appraise the activities of neighbouring farms. Councils had "maps" that were now much more visual.

New Zealanders had a greater appreciation of the country’s beauty, and the potential of aviation to materially improve their lives.

Big dreams all of a sudden seemed more real.

Chasing new ideas, White went into business in late 1937 with Frank Stewart, one of New Zealand’s pioneer cinematographers.

Undeterred, White published a definitive and longstanding history of New Zealand aviation (Wingspread, 1941), a book he impressively pulled together in less than a year.

White then joined the Air Force as a flying officer and subsequently as a photographer, working in a team of four publicists in the Pacific to capture a rich record of wartime events.

Among the results was a further publication (Fighters, 1945) and an exhibition in 1944 that included huge photographic murals, many hand-coloured — perhaps the first exhibition of hand-coloured photography in New Zealand.

White had figured out a hand-colouring technique with Frank Stewart, but required a new commercial venture, Whites Aviation, to blossom it to full effect.

The company’s primary aim was to be the "voice of New Zealand flying", through a monthly magazine also called Whites Aviation.

White’s sense of humour was part of the mix: "Whites Aim: To do the impossible immediately while realising the miraculous may take a little longer."

By any measure, the magazine was a huge success, offering a rich tapestry of industry information along with promotion of important social infrastructure, such as advocacy for airports and an early air ambulance service.

Alongside the magazine, Whites Aviation had its booming aerial photography service, securing multiple accolades, including one of the world’s most famous cloud pictures and one of New Zealand’s most popular and critically acclaimed photography books, Whites Pictorial Reference, published in 1952.

The company also offered photographs coloured by hand.

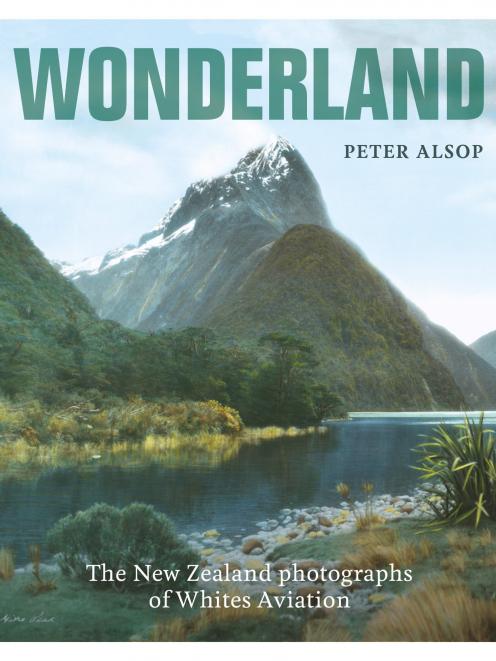

Art curator Athol McCredie reflects: "In the 1950s and ’60s, the company’s hand-coloured scenic images ... were a familiar item in homes and corporate foyers. Their popularity established the Whites ‘look’ as the standard photographic representation of New Zealand."

The picturesque photos were at the heart of the hand-colouring craze, particularly an 18-vista "Scenic Series" that White explained were "forever in demand ... and sold by the thousand".

The secret, he said, was that "every one [was] placid, restful; no angry skies, no arty approach. All were taken just as anyone would see them from the roadside or some popular vantage point".

While his eye was instrumental, Leo White never hand-coloured a photo himself.

Instead, he entrusted the studio to Clyde "Snow" Stewart (son of Frank Stewart) who was a talented colourist and expert in production.

Quite amazingly, given advances in printing and colour film, Whites continued hand-colouring photos until 1996.

To understand White’s achievements is to understand his operating environment and recognise the boundaries he stretched to excel — not just for himself but for the enhancement of professions, industries and the wellbeing of people touched by him and his work.

From high standards come higher standards and innovations, building social capital to greater levels than would otherwise be the case.

And White did it all in a nice way: with huge integrity, humour and charisma.

For White, his passion for aviation, photography and publishing was a cocktail he wanted others to experience and enjoy.

He set about building the aviation industry in myriad ways, including periodicals, publications and photographs that promoted the industry’s development and documented a record of New Zealand’s aviation history.

It was illness that killed White, not tragedy or old age, but his chronic asthma was conceived in the passionate pursuit of adventure: a pioneering trip to Northland’s Te Paki Station in 1927.

White died at his Auckland home in December 1967, aged 61. Obituaries referred to his sense of humour, his work ethic and a profound understanding of people, with friends from prime ministers to caretakers.

White loved family, aviation, publishing and photography.

But what he loved more was leaving them in a more advanced state than they were before.

Even when too short, that’s a life well lived.