Faced with uncertain times, lawyer Kimberly Lawrence has what she calls a "Blu Tack life plan''.

"I always have one,'' she says. "But it has to be adaptable''.

Lawrence is among the 55 high school pupils presented with Otago Daily Times Class Act awards for excellence a decade ago who are now mostly established in their careers.

She tries to plan as well as she can for foreseeable problems and does her best not to worry too much beyond that. However, she admits that "not worrying'' is a work in progress.

The future has never been certain. But in 2019, the pace and scale of change means no-one really knows what skills will soon be relevant and it can be virtually impossible to plan ahead.

The unpredictability encompasses everything from climate change and the impact of new technology on future careers to the growing gig economy.

MILLENNIALS, like the rest of us, also face deepening geopolitical tensions and economic uncertainty. Will student debt delay their financial goals or even their retirements? Will escalating house prices make home ownership possible?

We asked how they deal with the uncertainty.

"Embrace it,'' answered Jordan Horrell, the head of a high school English department. "Control what can be controlled and enjoy whatever it is that makes you happy. I don't feel like worrying really achieves anything, so there's little point in it.''

A couple said competing for short-term contracts and not being able to predict which jobs would be available in the future could be stressful. However, many were comfortable to "go with the flow'' and a few noted that the most exciting things they had done had happened because they took opportunities as they arose.

Solicitor Rosa McPhee said it had always been difficult to plan for the future and the key was being open to new ideas, and new ways of living and working.

Amber Hosking, legal counsel for an energy trader in Germany, felt it was important in an "ever-changing, information-overload world'' to figure out values and goals, build strong support networks and be willing to ask for help.

Data scientist Steven Cromb said uncertainty led his generation to make sure they saw the world sooner rather than later.

Builder Jeff Notman said the increasing uncertainty had not affected him and believed people had never had it "easier'' in terms of medical care, availability of food, career options and access "at their fingertips'' to almost anything they could possibly want to know.

A key question for Tearfund international programmes specialist Rosie Paterson-Lima was how young women such as herself planned for their futures, especially in a country that still had a "serious'' gender pay gap and in a city such as Auckland where living costs were high.

Many were not only unsure how and when to get into the housing market but faced barriers because of their ethnicity, gender, age, education level, disability or religion, she said.

"At school, I didn't think these struggles for women would still be so apparent in New Zealand in 2019.''

Several members of the group had changed plans since leaving school; some ending up in careers they did not know about then, others moving from their original areas of study to others they found more fulfilling.

Meteorologist Lewis Ferris preferred to keep his plans to a minimum so he could be "fluid'' in his decisions.

For PhD student Alastair Lamont, one problem with planning was getting to grips with how many options there were: "What I want for myself today could be quite different to what I want in a year's time. Combined with how fast things are changing in the world, this makes long-term planning quite hard.''

Completing studies, receiving awards, travelling overseas and marrying were among many highlights from the past decade that the group listed.

Conservation worker Luke Johnston got to 50 premier games for his "beloved'' Green Island Rugby Club while doctor Crystal Diong appreciated the opportunities presented by medicine: "When I was a medical student, I observed neurosurgeons use technology such as 'stealth MRI' to help remove a certain kind of brain tumour through the nose,'' she said.

"Fast-forward a few years and I was living in an extremely remote village in central Mongolia, drinking fermented horse milk and helping doctors treat patients in a small clinic ... without even a lab or an X-ray machine.''

Now in their 20th year, the Class Act awards celebrate the success of high school pupils in the Otago Daily Times circulation area and in fields as diverse as studies, sport and cultural activities. The winners are chosen by their schools and presented with their awards by the prime minister.

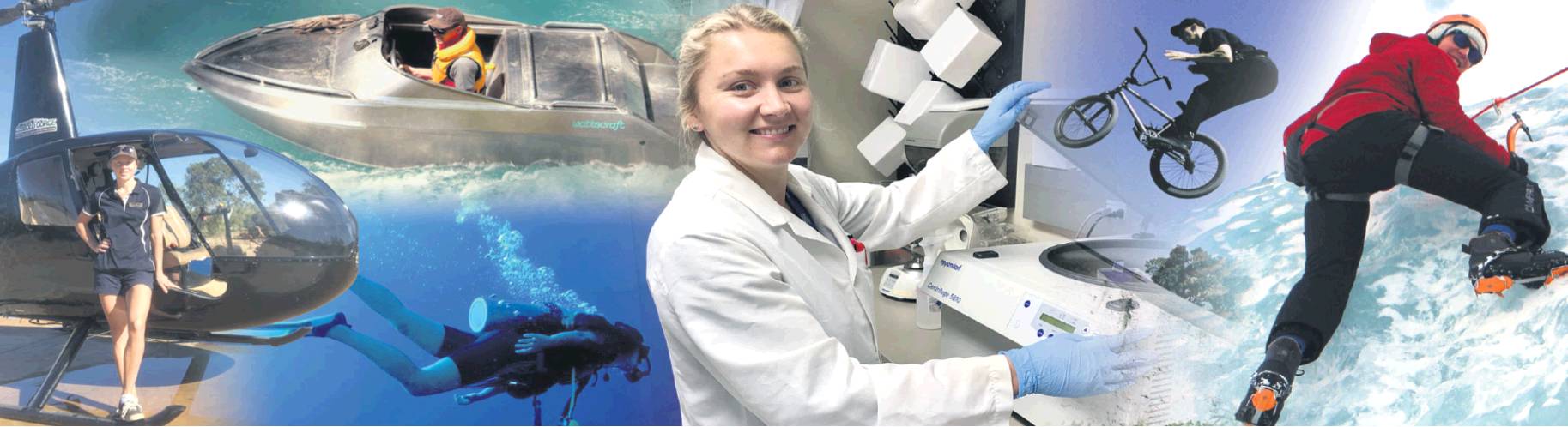

Working in a variety of fields from firefighting to flying, the 2009 group includes three software developers, four teachers and five doctors.

Kirsten Ward-Hartstonge is a postdoctoral research fellow in Vancouver, studying immune cells in childhood diseases such as type one diabetes and inflammatory bowel disease. At the University of Otago she helped to discover a population of immune cells associated with better survival in patients with colorectal cancer.

Paterson-Lima works with community development organisations to deliver programmes in India, Nepal and Indonesia.

Kelsey Brown, a senior advisor at the Office of the Children's Commissioner, leads the engagement process through which New Zealand's young people share their views on important issues.

Like many millennials, they are active not only about issues that affect them directly but causes that will have a positive impact on society.

Katarina Schwarz is fighting to end modern slavery, a problem that affects an estimated 40 million people.

Alice Marsh created a community of young professionals driving sustainability in their workplaces and is developing a website aimed at making New Zealand charities more visible. In her time at medical school, Diong started 100Percent, a non-profit organisation that saw students raise money for causes of their choice by volunteering their time as tutors.

Trying to achieve a healthy work-life balance was the issue that recipients most struggled with in their personal lives. Others mentioned ones related to this, such as finding time for all the things that were important to them, staying connected to friends and family and keeping active. Another concern was housing affordability.

Inequity, apathy and indigenous people having to defend their land were all regarded as important international issues. However, climate change easily rated as the most pressing global problem.

Corwin Newall, a software developer and father of one, said given the environmental footprint of an extra person potentially living for most of a century, he was trying to decide how many children to have: "We are absolutely f...ed. And not enough people are panicking enough about it.''

Others talked of bridging the gap between science and society by sharing research with the public in ways that were readily accessible. PhD student Hayden Dalton: "A general public that is better informed and armed with facts is important in a time of increasing uncertainty.''

Patrick Kearney, a former maths teacher now studying for a bachelor of science, had his own take on the unpredictable times.

"The future is up for grabs. It's not inevitable that our lives should be insecure,'' he said. "Economic and social relations can be changed and technology managed, to empower people and to give them stability instead of sidelining them.''

Class Act 2019

This year’s Class Act recipients will be profiled in an Otago Daily Times publication on Wednesday, the day before Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern presents them with their awards at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery.

Watch live

Watch live coverage of this year’s Class Act ceremony on Thursday from 3pm at www.odt.co.nz.