On December 1, 1874, the Otago Acclimatisation Society, the forerunner to Otago Fish & Game Council, launched the historic three-month trout fishing season, laying the foundations for the long-standing Kiwi tradition of freshwater angling.

What began in Otago has grown into a popular national pastime today, more than 130,000 anglers each year heading to New Zealand’s rivers, lakes and streams.

While rods and reels may have changed, the core experience endures - the pursuit of an elusive fish with a fly, lure or bait.

Freshwater angling is deeply embedded in our national identity. For generations, angling has connected Kiwis to a shared passion to escape into nature, reflect and unwind, enjoy each other’s company, and bring home fish for the table.

The anniversary was not only a celebration of sporting history but also a testament to anglers’ enduring commitment to fisheries management and conservation.

The season countdown

Anglers relish the days counting down to a season opening. This one had been several years in the making.

In September 1874, the Otago Acclimatisation Society met to discuss whether trout fishing would be permitted in certain waters of the province, six years since imported ova were incubated at Ōpoho Stream, then successfully released.

Up until then, apart from illegal poaching, the trout had been left alone to become established. The society considered that any trout fishing should be restricted to the streams where they had been liberated in late 1868 and early 1869, where it was agreed releases had been "abundantly successful".

In November, a limited number of streams were gazetted for the inaugural season. They included the Water of Leith, Shag River, Silver Stream, Waitati River, Kakanui River, Waikouaiti River, Island Stream and "Fulton’s Creek", in West Taieri, thought to be now part of the Contour Channel.

A question on the fly

The Otago Acclimatisation Society believed trout fishing in the province would be an agreeable change to the "monotony of country life", and "above all things provides a healthy outlet to the superfluous energies of our young men".

But when it came to the matter of sport, whether Otago trout would take an artificial fly was open to speculation.

The Otago Witness reported in September 1874 there had been some doubt whether trout in the province "will afford the same sport to fly fishers that they do at home". It was suggested that, though trout in Otago grew to be "enormous", nothing would tempt them to rise to an artificial fly. The question would soon be answered.

Opening day

On opening day on December 1, Alexander Campbell Bell cast his line in the Water of Leith, in Dunedin, and made history by catching the first legal trout under licence in New Zealand.

In one afternoon, Mr Begg basketed 20 fish weighing 13lb (almost 6kg), all caught on the fly, historical records show.

It was reported that "good baskets" of trout were made by anglers in a few hours’ fishing.

The Witness also reported in January 1875 that 32 licences for brown trout fishing had been taken out at the Provincial Treasury.

"The fishing, however, has yet been confined to the Water of Leith and the Shag River. In the former stream, some fine baskets have occasionally been taken; but in the latter, the number of fish that up to the present time has been caught is not very great.

"The kind of fly which will charm the Shag River trout has not evidently been yet hit upon. Of the fish being there in considerable numbers there can be no doubt.

"One Dunedin gentleman, who succeeded in bringing to grass two fine fish, weighing respectively seven and five pounds, reports that, in the lower part of the river, the trout may be seen about dusk both rising and leaping after the white moths that are so abundant."

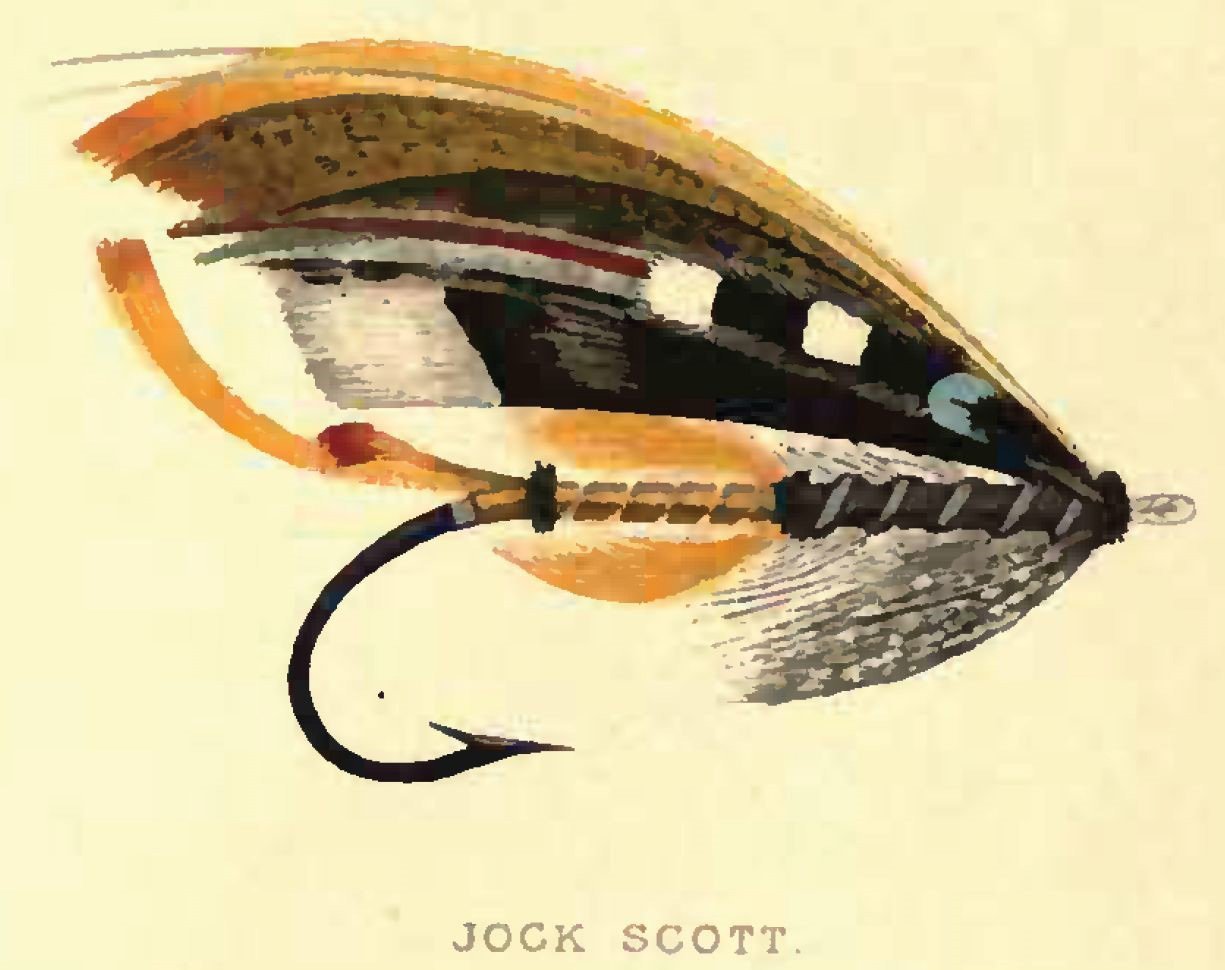

On which flies would best tempt trout, the Witness later added: "Even in the Water of Leith a ‘loch’ fly has to be used, and in the Shag River it is thought that nothing short of a ‘Jock Scott’, or, at least, something like it, will wile the monsters from their pools."

In summing up the end of the inaugural season, the Otago Witness told a tale of two rivers.

Notwithstanding the fact the Water of Leigh had been "industriously fished" during the last few months, the trout still seemed to be very numerous, and some enthusiastic anglers had been "tolerably successful" during the last two days.

Of the Shag River, while some anglers complained that the trout could not be caught, the Witness reported, " ... our informant believes that they will take the fly, and all that prevents them from being landed is want of skill."

A century and a-half on, perhaps some things have not changed. Large trout that cruise the long, lazy pools of the Shag River/Waihemo continue to test the skills of even the most experienced trout anglers.

A palatable debate

Another question on Dunedin migrants’ minds in 1874 was the table qualities of the locally caught trout, and not everyone was in agreeance.

"It was mentioned that great difference of opinion exists amongst those who have been fortunate enough to secure specimens of the brown trout in Otago, with regard to their edible qualities," the Witness reported.

"Some have reported them to be coarse, and muddy in flavour, while others assert that the fish are equal in flavour to the finest burn trout at home."

The Witness scribe somewhat resourcefully then wrote: "Our reporter knows of only one way by which this disputed point can be settled. This to successful anglers only".

In January 1875, another Witness report said large trout caught from the Shag River were in fine condition and tasted almost like salmon.

Water under the bridge

The Water of Leith has changed drastically over the past 150 years. The 25km river has been highly modified by agriculture, forestry, urbanisation and flood protection. Through the heart of Dunedin, its lower sections flow along concreted banks, weirs, past the shadow of the University of Otago clocktower, under walkways and road bridges, and towering walls before spilling into Otago Harbour.

The Leith has many migration barriers, most of which trout can pass throughout the year, but several weirs are only passable during high flow.

While the river still holds reasonable numbers of juvenile brown trout and migratory adults that make their seasonal passage upstream to spawn, legal fishing is today restricted to downstream of the confluence of the Water of Leith and Lindsay Creek, next to Dunedin Botanic Garden.

Science-based management

Since 2018, the Leith catchment (its Māori name is the Ōwheo) has been closely monitored through an electro-fishing survey by the University of Otago and Otago Fish & Game. The field work and observations are carried out by postgraduate students from the Zoology Department, and they help to inform the management of the fishery and habitat.

Their findings have identified critical spawning habitat, impacts of flood events, and the importance of connectivity for migratory fish. Upper sections of the Water of Leith and Lindsay Creek holder higher densities of trout than lower sections. While numerous, trout in the upper sections are smaller than those downstream.

The licensing system

Securing a licence in 1874 cost £1 - equivalent to about $160 today - for access to Otago waters for three months. In comparison, today an adult whole-season fishing licence, covering most of the country for 12 months, costs slightly less.

The licensing system remains central to Fish & Game’s efforts to manage freshwater fisheries across New Zealand, except for Taupō, and to protect and enhance freshwater ecosystems.

Anglers’ licences fund vital access work, conservation programmes, habitat restoration projects, and water quality monitoring.

Otago Fish & Game Council is solely funded by the sale of fishing and game hunting licences. It receives no government funding. This user-pays model ensures anglers actively contribute to safeguarding these waterways for future generations, preserving fish populations, and enhancing habitat across the region.

Rod and reel

Alexander Campbell Begg was active on the Otago Acclimatisation Society, including as vice-chairman from 1891 to 1895. In recognition of his dedication to the society, Mr Begg was awarded a custom Hardy split-cane fishing rod in January 1894. The rare rod was donated by his descendants to Toitū Otago Settlers Museum in 2023.

Mr Begg’s rod was typical for its time.

Fly reels were also made of brass, aluminium or ebonite (a hard rubber material). Brass was common for is durability but were heavy. They sometimes had a basic click-check mechanism to provide minimal resistance and prevent the line over-running. Anglers relied on their hands and skills to control line tension while fighting fish. Reels were sized to hold silk fly lines, which required careful maintenance, such as drying and oiling, to avoid rotting.

Leaders were crafted from gut (often silkworm gut), which was delicate and prone to breaking but nearly invisible in the water. Flies were handmade using natural materials such as feathers, fur and silk. Patterns were often British imports, but New Zealand anglers began adapting patterns to local insect lift.

While split cane rods still have their place among enthusiasts, today’s fishing rods are mostly made from carbon fibre or fibreglass. Continued advancements in technology are making rods even lighter and stronger. Customisable actions also cater to specific techniques, such as dry-fly fishing or nymphing.

Spin fishing has also made many technological leaps forward. Recent advancements such as soft baits and soft plastic lures, highly sensitive carbon rods and braid lines are giving anglers more scope to explore and develop in their chosen passions.

An enduring heritage

Angling is woven into the fabric of New Zealand’s outdoor heritage.

"Trout are a part of our ecosystem, recognised as a valued introduced species," Otago Fish & Game chief executive Ian Hadland says.

"Looking back on the last 150 years, we are proud of the unbroken history of fisheries management and the benefits that has brought to anglers and the environment. We are well set up to continue that work.

"As we look ahead, we are committed to working alongside mana whenua, communities, and all New Zealanders to ensure that our waterways and wetlands thrive.

"We encourage all New Zealanders to celebrate this anniversary by casting a line, exploring a nearby river, or simply appreciating the beauty of our natural environment."