DUSKY SOUND - FIRST PAKEHA SETTLEMENT IN NEW ZEALAND

The only Pakeha settlements established in New Zealand before the end of the 18th century were in Dusky Sound. While today this is one of the most remote parts of New Zealand's coast, it was then one of the better-known localities, having been described and charted by Cook. It must also have seemed comparatively safe: at Queen Charlotte Sound and the Bay of Islands, the only other well-known harbours, there had been European deaths at Maori hands. Dusky Sound was also out of sight of the colonial authorities in New South Wales and beyond the direct control of any European authority. This remoteness was one of its primary attractions.

THE BRITANNIA SETTLEMENT, 1792-93

The first commercial venture to New Zealand was undertaken by Captain William Raven of the Britannia. His ship had departed England in February 1792, with a cargo of food, clothing and other supplies for Port Jackson, and a licence from the East India Company to go sealing in southern waters. Raven's plan was to hunt seals in Dusky Sound for the China market, where he hoped to exchange them for spices, teas and silks for sale in Britain. Before leaving Port Jackson, Raven was contracted by a group of military and civil officers to proceed to the Cape of Good Hope to procure a cargo of cattle, clothing and other supplies. To accommodate these two commercial objectives, the Britannia departed Port Jackson for Dusky Sound, where, on 1 December 1792, a gang of men were left to hunt seals while the ship sailed on to South Africa for supplies.

The Britannia settlement was located in Luncheon Cove on Anchor Island. Visited and named by Cook in 1773, this is a tiny, almost landlocked harbour, well protected from ocean swells by a surrounding cluster of small islets, and close to the Seal Islands on which there are breeding colonies of fur seals. Evidence of the settlement was discovered in 1897 by conservationist Richard Henry, who dug with a spade in several places there, locating a clay floor, two pits and a midden of charcoal, cinders and scrap iron. It was another 100 years before these were subject to systematic archaeological excavation.

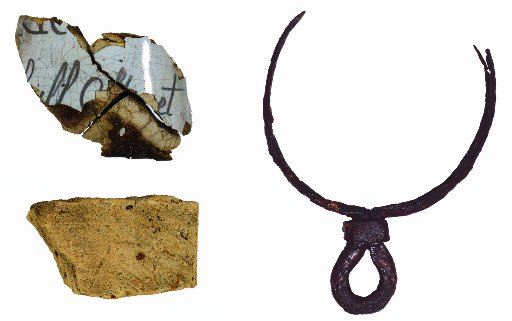

While the presence of William Leith's sealing gang in Dusky Sound has been well known in the historical record since the late 19th century, the significance of this site as the first Pakeha settlement has largely been overlooked. Archaeological evidence located here - the forge and its by-products, a crude arrangement for steam-bending of planks and a stone keel support - provides a link to the first ship built in New Zealand, and also the first in Australasia constructed in local timbers. The domestic remains, slight as they are, constitute the earliest pottery and glass artefacts yet to be recovered in this country. They are the only surviving links with the first Pakeha to have lived on New Zealand's shores.

Living in New Zealand presented a range of challenges for early Pakeha. Significant amongst these was the fact that they had come to a place where the prevailing rules of social and economic interaction were not those of their homeland. Pakeha access to land and the use of resources for economic activities, whether hunting seals or whales, harvesting timber or grazing sheep, required Maori consent and, usually, payment for use-rights. When Pakeha failed to seek permission or refused to pay, Maori sanctions such as taua muru were imposed. Failure to observe strictures of tapu could have fatal consequences, as Marion du Fresne's fate revealed. The Maori world was often buffeted by competition between the leaders of hapu and iwi, in which early Pakeha visitors and settlers were often unwittingly caught up. They were nearly always reliant upon the patronage of particular rangatira for their protection, and on local hapu for initial supplies of food and shelter. Even as these relationships began to fade, toward the middle of the century, Pakeha settlements and towns remained dependent to a significant degree on Maori food production. Only in Wellington, where George Grey's aggressive use of military force had, by 1848, dispossessed local Maori of their most productive land, did this reliance diminish before the late 1850s.

Cross-cultural marriage also played a crucial part in the "mixed-race" settlements that emerged in New Zealand from the 1820s. Pakeha men and their Maori partners predominated in communities such as those at Sealers Bay on Codfish Island/Whenua Hou, the early ship-building settlements in Port Pegasus and the Hokianga Harbour, Browne's spar station at Mahurangi, and at most of the shore-whaling stations of the 1830s, 1840s and beyond. In many cases, especially at whaling and timber settlements, marriage between the station manager and a female relative of the rangatira was arranged as part of negotiating rights to occupy land and harvest resources. Such marriages followed traditional Maori practice, involving gift exchange; use-rights for land were typically exchanged for imported goods. At one level these were strategic alliances for both parties, securing access to resources and protection for Pakeha and control over the supply of imported goods for Maori, but for the most part they were "a combination of love, comfort, politics and pragmatic need". Men of lower rank on the whaling and timber stations typically married Maori women of lower rank within their society, in ceremonies that generally followed secular British common-law traditions.

Critical to all the early Pakeha towns was the provision of basic infrastructure, such as roading, water supply, waste disposal and facilities for civic purposes. Plans drawn up for early towns did not always fit comfortably with the realities of the landscape they were imposed upon. Felton Mathew's "cobweb" design for the ridge east of Queen St in Auckland proved impractical, never coming to fruition, and his two public squares on the ridge to the west were abandoned by the time buildings were constructed there in the 1850s.

In Dunedin, surveyor Charles Kettle laid out a grid pattern of streets that paid no heed to the hills, streams, lagoons and low-lying boggy ground that confronted early settlers there. Some of the accommodations they made to cope with this have been revealed through recent excavations.

During construction of the Wall Street shopping mall in Dunedin in 2008, a timber causeway was discovered more than a metre below the ground surface on which buildings of the late 19th century had stood. It was constructed of axe-cut timbers, mostly kanuka and mapou, along with other woods that had been common on the lower slopes of the hills surrounding Dunedin when the first Pakeha settlers arrived. There were two main layers of timbers: an upper course of smaller branches and limbs, laid horizontally across three sets of longitudinal runners. Where the underlying mud was deepest, there were also several large cross-members beneath the runners. Flax leaves under the logs indicated that the causeway had been laid over flax-covered ground, and its orientation at a diagonal to the section boundaries, along with the scarcity of artefacts found in direct association, indicate that it was one of the first constructions in the vicinity, placing it in the late 1840s or early 1850s. The causeway had clearly been laid across a muddy swale or stream course to provide a dry pathway for pedestrians crossing the edge of the North Dunedin flat. It provides a stark reminder of the conditions that prompted many locals to call their town "Mud-edin".

Pakeha colonisation of New Zealand was a drawn-out process that changed in character as it took place. It began through scientific curiosity and speculative commercial ventures, rather than political intent to exert control or promote settlement. Although James Cook "took possession" of the country for the British Crown in 1769, there was no attempt to act on this before the 1830s. But migrants from the Anglo world trickled into New Zealand and began living there, alongside tangata whenua, for almost 50 years before the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. These early Pakeha lived in a world framed and dominated by Maori. This situation began to change soon after 1840 with assertions of Pakeha political and military power, and disquiet and resistance from Maori. However, until the end of the 1850s early Pakeha towns remained economically dependent on Maori food production, and armed conflicts between Maori and colonists or the British Army ended in stand-offs, rather than decisive victories.

After 1860 the onset of a more brutal phase of colonisation by military force and confiscation of Maori land and resources changed the balance of power. The Maori population continued to fall, mostly due to disease and deprivation, while Pakeha numbers increased fivefold, through immigration and "hyper-reproduction" (a very high rate of natural increase) as settlers produced families that were larger and healthier than those in Britain.

The talk

Ian smith talks about his book at Otago Museum, today (Saturday, Nov 23) at 5pm.