Those with ears to hear, heard the Waimatā speak in 2023, when the river roared down from the hills of Te Tairāwhiti carrying its destructive cargo of slash to litter the beaches of Tūranga/Gisborne.

All is not well, it said.

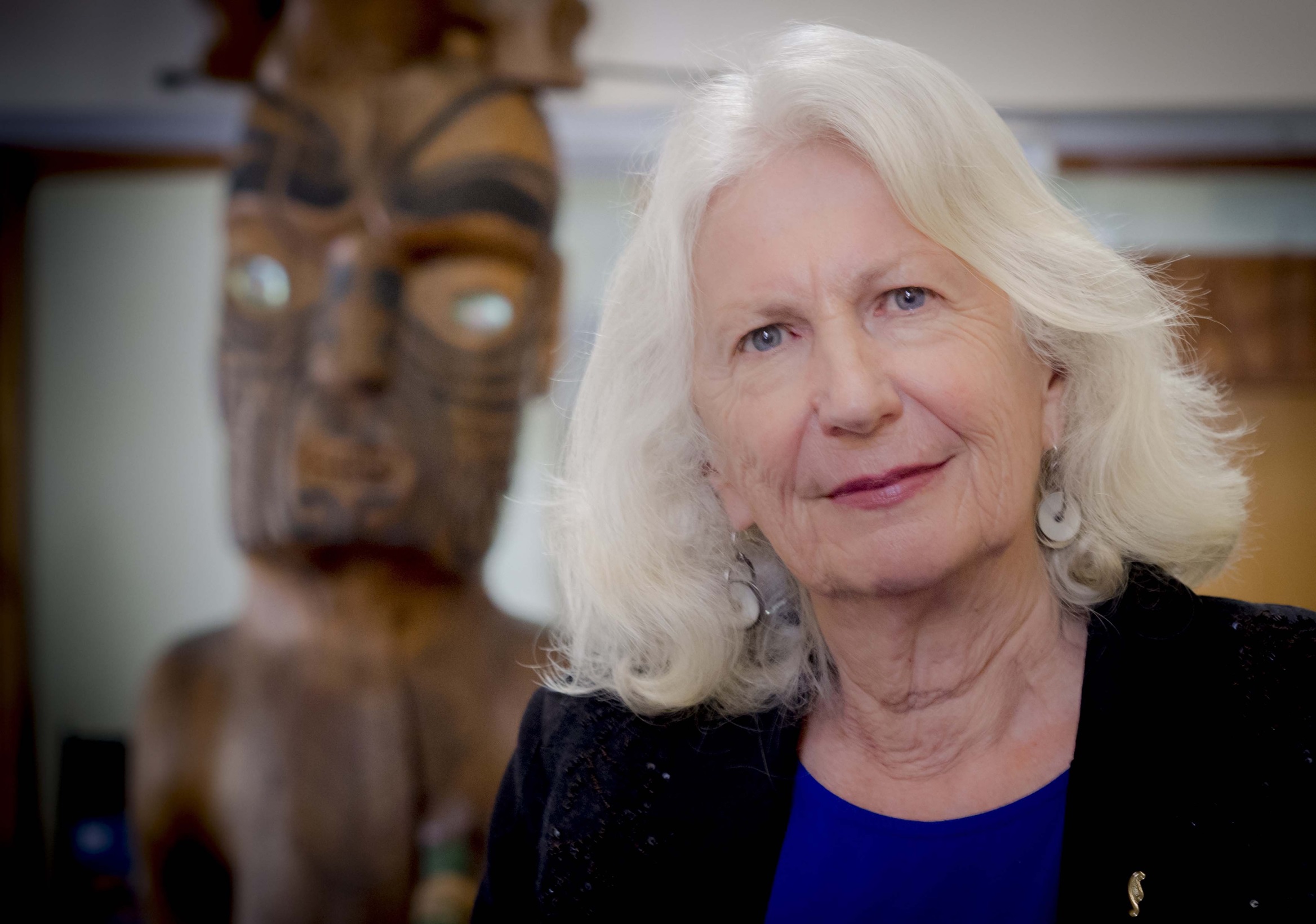

Dame Anne Salmond heard, and saw, what was going on. For, among other reasons, she knows that waterway better than most.

The distinguished professor of anthropology, who grew up in Gisborne, is involved in a project called "Let the Rivers Speak", a trans-cultural, trans-disciplinary research programme that has included work on the Waimatā for the past seven years.

"We’ve had people working on the river and studying its idiosyncrasies and sediment flows and the life around the river, including the people," she says on a video call from Auckland.

Writing about the project a few years back, with fellow researchers, Prof Salmond discussed the deep assumptions that underlie relationships between people and the planet, and how these translate into very different ways of relating to waterways in Aotearoa New Zealand.

On the one hand, in te ao Māori, people are intimately connected to waterways through whakapapa — rivers and lakes are the tears of Ranginui. By comparison, modern Western approaches are still based on an idea of "dominion" over the earth, in which all life has been created purely to serve human purposes.

That didn’t go so well when Cyclone Gabrielle arrived and the heavily modified plantation forestry land of the Waimatā catchment couldn’t cope. The human purpose to which it had been turned, logs and the associated slash, bulldozed its way downstream accompanied by countless tonnes of silt.

However, that’s not what this story is about, or not entirely.

Prof Salmond is on the small tablet screen to talk about the Treaty Principles Bill, and perhaps one or two other things, as she is headed south next month for the Wānaka Festival of Colour, where she’ll share a session on "Tearing up the Treaty" with Kassie Hartendorp (Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa), the director of ActionStation.

These things are connected in Prof Salmond’s telling, the harm wrought in Te Tairāwhiti and various legislative initiatives under way in the country. And, indeed, a view abroad in the wider world.

In Aotearoa, we’re talking about, at least, the Treaty Principles Bill, the Regulatory Standards Bill and the fast-track legislation.

Prof Salmond is certainly bracketing them as all part of a trajectory that privileges the individual over community, wealth over democracy, and avarice over the environment.

The professor, a celebrated scholar with awards and prizes too many to mention, author of Between Worlds: Early Exchanges between Maori and Europeans, which won the Ernest Scott Prize, and the Montana Medal-winning The Trial of the Cannibal Dog, among a long list of publications, and who was made Dame Commander of the British Empire for services to New Zealand history, has been a vocal critic of the Treaty Principles Bill, which she describes in terms almost as blunt as Tuhoe kaumatua Tama Iti (he called it "dumbarse").

The Act party Bill is a travesty, she says, which is precisely what she told the select committee.

"I said, it’s like if I went to France, and if I couldn’t speak French at all — I can speak a bit at least. But if I couldn’t speak French at all, and I went to France, and they were having a big debate about a key constitutional document of theirs. And somehow or other, I intervened, and I, not speaking very good French, couldn’t even read the document, started instructing them about the basic principles of their constitution. They would think I was a complete lunatic, or a fool, but certainly someone overcome with hubris."

What we’re doing with Act’s Bill, is having a debate about what Act — apparently unable to read the original te reo Māori — wishes the Treaty had said, Prof Salmond says.

"It’s a real perversion of what the Treaty is all about. Because they’re trying to make it about private property. That wasn’t even a concept in 1840, really."

Indeed, it’s the minor party’s obsession with private property, shared with others occupying a particular wavelength of the political spectrum, that runs through these various legislative initiatives, in the professor’s analysis.

She views its Treaty Bill as part of an agenda to elevate individual liberty and private property rights in our polity above all other considerations.

"I think that’s exactly what’s going on. Because, in that particular philosophy, collective rights are seen as an impediment to progress, so-called, and they want to reduce everything to individual rights and private property rights."

In its election policy document on the Treaty, Act said as much.

"The protections of property rights against the desires of the government are weak. Repeatedly, governments seize or impose controls on peoples’ [sic] property well beyond any legitimate public interest and ignore the rights of ownership. Act believes the principle of rangatiratanga over one’s own property is a basic human right," the document says.

It’s a more than controversial use of "rangatiratanga", which, as the professor has previously clarified, carried the meaning of "independence" in He Whakaputanga, the 1835 Declaration of Independence.

The flipside of extending this "independence", this freedom of action, to private property owners, is that the Tiriti guarantees of "te tino rangatiratanga o o ratou wenua o ratou kainga me o ratou taonga katoa" (the unqualified exercise of their chieftainship over their lands, villages and all their treasures) to iwi and hapū, are obstacles to be removed.

Then, as a further element of the same programme, Act’s proposed Regulatory Standards Bill could run interference on any future attempts to restrict, or "impair", an individual deploying their capital as they want to.

It might look a benign enough ambition on the face of it, freeing the individual to engage in the free market as they see fit.

But Prof Salmond sees more.

Helping to inform the professor’s view of the politics at play has been a deep dive into the Geneva school of neoliberal economics favoured by Act and its supporters. Included in her reading were books by Quinn Slobodian, a Canadian historian, Globalists and Crack-up Capitalism. He has another book out shortly, Hayek’s Bastards, referencing a leading figure in the Geneva school, Austrian economist Friedrich von Hayek.

Hayek was an evangelist for the market, which he regarded as a super processor of information, vastly better able to understand the workings of an economy than any human.

"As an anthropologist, I immediately start thinking, hmm, this is interesting. OK, so we’ve got this kind of quasi-deity almost, you know, something that’s beyond human comprehension," Prof Salmond says.

"But then it’s got these special classes of people, the entrepreneurs, who tune into the market and are able to read its signals, its cryptic omens, and oh dear, now you’ve got a priesthood of people that serve this kind of ineffable, unknowable force.

"And what the state ought to do is to actually protect all those people from interference.

Slobodian himself sees neoliberalism as an ongoing project to protect capitalism from different forms of democracy, the latest threats, as this brand of market fundamentalism sees it, being environmentalism, feminism and affirmative action.

In a similar vein, in their recent book The Big Myth, Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway argue that according to this view, governments’ actions only ever interfere in the proper functioning of the "free market", so they should stay out of the way lest they prevent it doing its "magic".

The United States-based pair say if this sounds like an argument fashioned in the interests of big business, that’s because it is. The contention that markets, and their actors, are free and good, and the government bad, is an economics bought and paid for by those who stand to benefit. The book’s subtitle is How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market.

They quote the 18th century poet and naturalist Oliver Goldsmith: "Ill fares the land, to hastening ills a prey/Where wealth accumulates, and men decay".

In his recent book answering the argument of the free market purists, The Road to Freedom, US professor of economics and Nobel Prize winner Joseph Stiglitz quotes Isaiah Berlin, "Freedom for the wolves has often meant death to the sheep".

He says by advocating for "unregulated, unfettered markets", these proponents of neoliberalism are arguing for a very narrowly defined version of freedom — leading to "freedom of a few at the expense of the many".

Prof Salmond can see the wheels of democracy flying off the cart, a betrayal of both the Enlightenment values the West claims for itself and the Māori worldview that Te Tiriti promised to uphold back when it was signed in 1840.

Then, te ao Māori was grounded in whakapapa, employing a relational logic expressed through te reo.

"It’s about balance in relationships. And so it’s always been quite democratic. If you read the early accounts you see that the early Europeans were astounded that Māori were so democratic in the way they practised their politics. You know, they were always having meetings about everything and having to make collective decisions, and the rangatira couldn’t just tell them what to do."

Prof Salmond contrasts it with what’s being discussed for the Regulatory Standards Bill, under which a board appointed by the minister, David Seymour in this case, would wield enormous power.

She is struggling to see how it might deliver anything resembling the common good.

"I mean, that’s what democracy’s for. If you start eliminating the common good, you’re eliminating democracy, let’s be blunt about it."

Where it ends up, she says, is with someone like Elon Musk, who is able to aggregate enormous wealth and power and wants to be able to operate without any constraints.

"And so they’ll go out and they’ll destroy, for example, democratic institutions, so that they can do what they want."

Prof Salmond is hearing the cries from the US first hand, as that process rolls out.

"I’m a former associate of the National Academy of Sciences and I’m getting these desperate messages from the States at the moment about what’s happening with the scientific project there. It’s just appalling. People are not being allowed to be empirical any more and test ideas against evidence if they happen to contradict doctrine. And so I don’t want that to happen in New Zealand."

Anthropologist that she is, Prof Salmond recognises how deeply some of these ideas are embedded in the ancient mythologies of the West.

It’s the Great Chain of Being, she says, a very simple idea that goes back to the Greeks, of a tiered cosmos. God is at the top, then there’s the divine sovereign, the aristocracy, the commoners, and so on down to sentient and non-sentient animals, insects, plants, and, finally, right at the bottom, the earth.

"So you get the idea of the earth as a resource and ecosystem services and all this kind of stuff, the earth is here to serve human beings, which of course is mythological. It wasn’t created for that.

"We tend to think of Europe and the West as being purely rational and all our ideas are somehow founded in deep truths and everybody else is hampered by superstition and mythology, but it’s not the case. And I think you can see that. You can see the resurgence of that kind of mythology in the States at the moment."

It manifests in Donald Trump’s autocracy, his cries of "drill, baby, drill", and bodes ill for both the earth and its people.

"We’re destroying the planet in the process, or at least as a place for us to live," she says. "The planet itself will probably be fine. But species that destroy their own ecological niches do go extinct."

Prof Salmond says she is speaking out at this moment out of a sense of public duty, fulfilling the role of the public intellectual.

"It’s not because I enjoy contention, because I don’t," she confirms.

"I like being in positive spaces. But I think we’re in real danger. I think the world, I think the planet’s in real danger as a place for human habitation. And I’ve got grandchildren that I adore. And I think our democracy is at risk. And I’m not the only one that thinks that."

New Zealand can still choose to be an oasis of sanity in a mad world, she says.

"I think that’s what’s going to generate prosperity. You know, if we’re an oasis of sanity in a mad world, there are going to be a lot of sane people that want to look for an oasis."

New Zealand had a look at the alternative when Cyclone Gabrielle turned the Waimatā River, among other East Coast waterways, into a wrecking ball.

Prof Salmond says the billions of dollars of damage was caused in part by forestry companies, largely based offshore, being allowed to minimise their costs by operating in a way that turned out to be very dangerous.

The companies were Forestry Stewardship Council certified which means, according to that standard, they should not be making money at the expense of the forest resource, the ecosystem, or affected communities.

However, investigations following cyclones Hale and Gabrielle found their operations had not been properly audited — properly regulated — and certificates were suspended.

Freedom for some had restricted the freedom of the many downstream.

The talk

"Tearing up the Treaty", Dame Anne Salmond and Kassie Hartendorp in conversation at the Wānaka Festival of Colour, Pacific Crystal Palace, Saturday April 5, 11am.