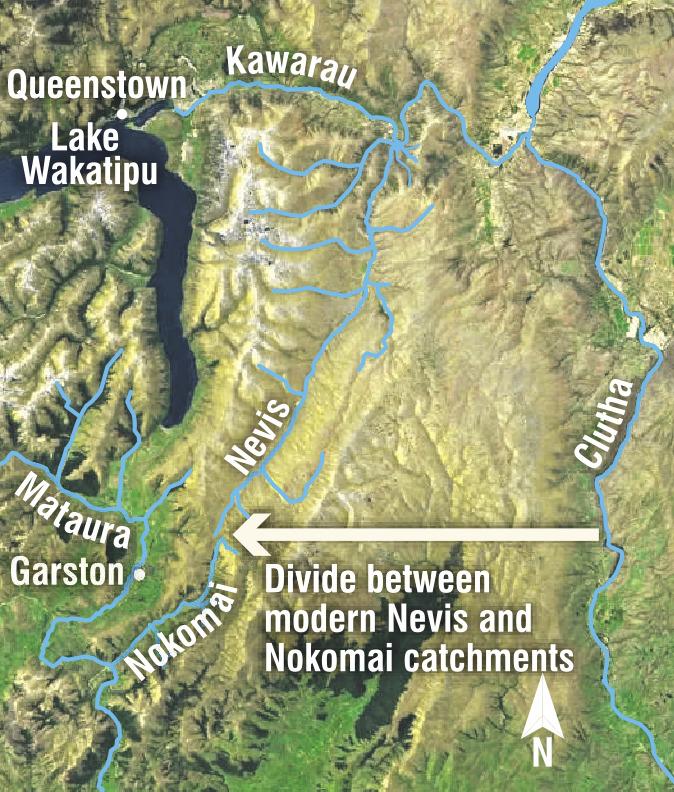

Geologists have long suspected the Nevis River once flowed south into the Nokomai River (and thence to the Mataura). Much of the current-day path of the Nevis is very flat and the small fall (just 250m over 30km) is thought to have arisen during the Pleistocene, about 500,000 years ago, when an earthquake raised the land just east of Garston.

Water always flows downhill and so earthquakes can change the flow of local rivers and streams. In this case, geological uplift led to the reversal of the direction of flow in the Nevis, a phenomenon known as "river capture". The Nevis became part of the Clutha catchment, rather than draining into Southland.

Remarkably, this scenario has been corroborated by an evolutionary genetic study of species of native fish known as galaxiids. These members of the genus Galaxias, include the well-known inanga or whitebait (Galaxias maculatus), as well as the giant kōkopu (G. argenteus).

Scientists have only recently come to realise just how many species of Galaxias there are. The Department of Conservation estimates that Aotearoa New Zealand has about 30 species, but half of them are yet to be formally named.

Sadly, today, many of these non-migratory species are on the verge of extinction, threatened by predation by introduced trout, as well as habitat degradation, such as bankside erosion and sediment pollution. They usually occur as remnant populations in a few trout-free locations, including parts of the Nevis River and its tributaries.

One species, the Gollum Galaxias (Galaxias gollumoides), gets its name from the Lord of the Rings character as it is "a dark little fellow with big round eyes who sometimes frequents a swamp". It occurs broadly across Southland and Stewart Island, but critically for our river-capture hypothesis, not in the Kawarau or elsewhere in the Clutha system.

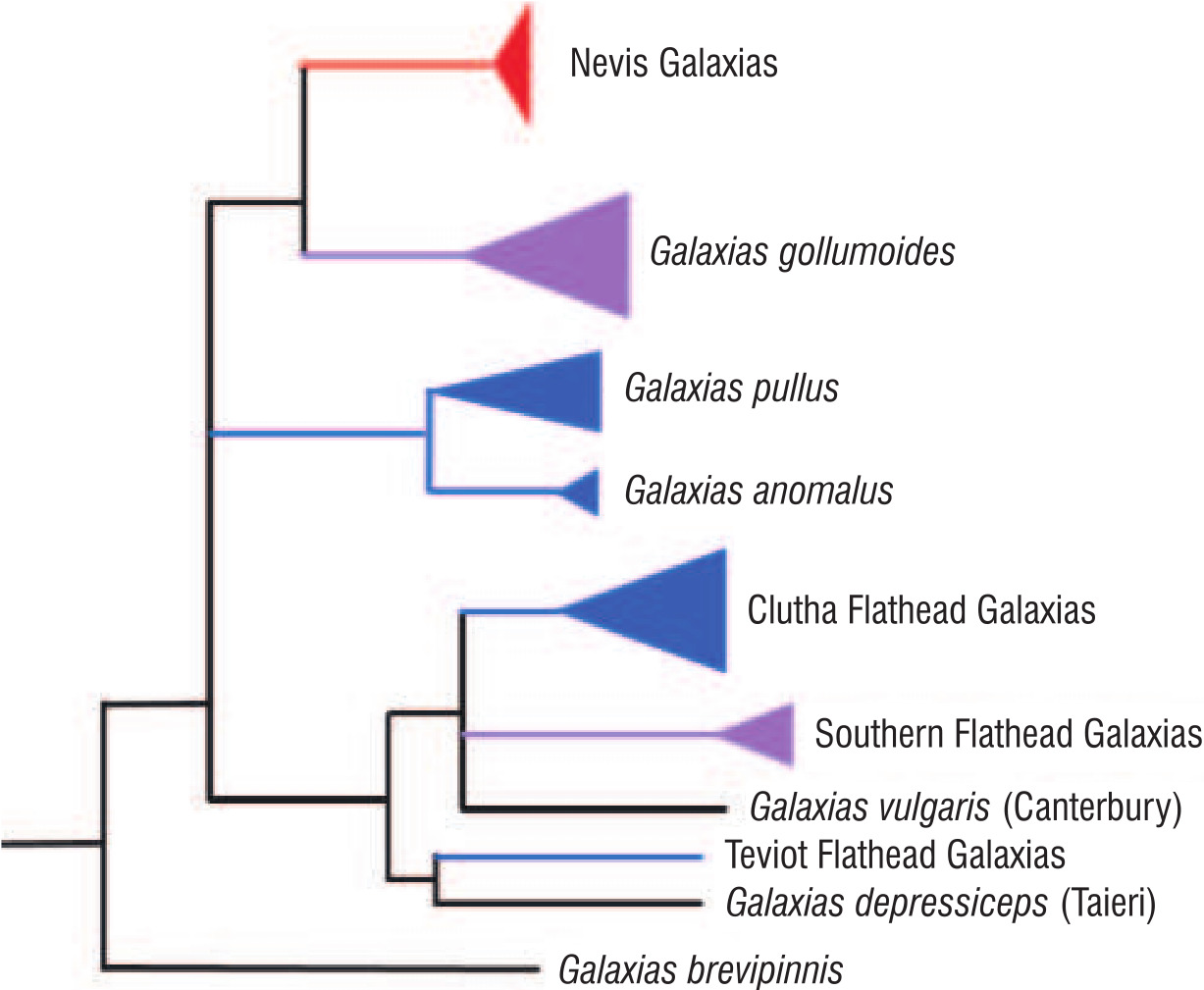

The genetic investigation of G. gollumoides and some of its relatives produced the evolutionary tree shown here. Species from the Clutha catchment are coloured blue; those from Southland purple. The species from the Nevis River is shown in red.

The tree shows the Nevis Galaxias is the closest relative of G. gollumoides. Indeed, at the time, they were considered to be the same species, but we now realise they are close but different. More recent genetic work has discovered further species and clarified some relationships, but these refinements do not affect our Nevis story.

This sister-species relationship reveals the Nevis Galaxias is descended from the same ancestor as the widespread G. gollumoides.

The best explanation of their anomalous distributions is river capture. Ancestors of the Nevis Galaxias colonised the Nevis River aeons ago, when it drained into the Nokomai. After the uplift event and the reversal of the Nevis, these fish were isolated from their Nokomai relatives and, over time, diverged to become a new species.

Genetics even allows us to estimate the date at which this evolutionary separation occurred. Depending on the method used, the best estimate is 800,000 years ago, a date roughly consistent with the geological evidence.

Who would have thought genetics would be able to confirm a hypothesis about ancient geological events?

So next time you are off to the wineries of Gibbston, raise a glass to the small native fish who survive in the Nevis River. They have been there since well before humans ever thought of making wine!

Hamish G. Spencer is Sesquicentennial Distinguished Professor in the Department of Zoology at the University of Otago.