Photographs are taken in a split second, but the stories behind them can span many years.

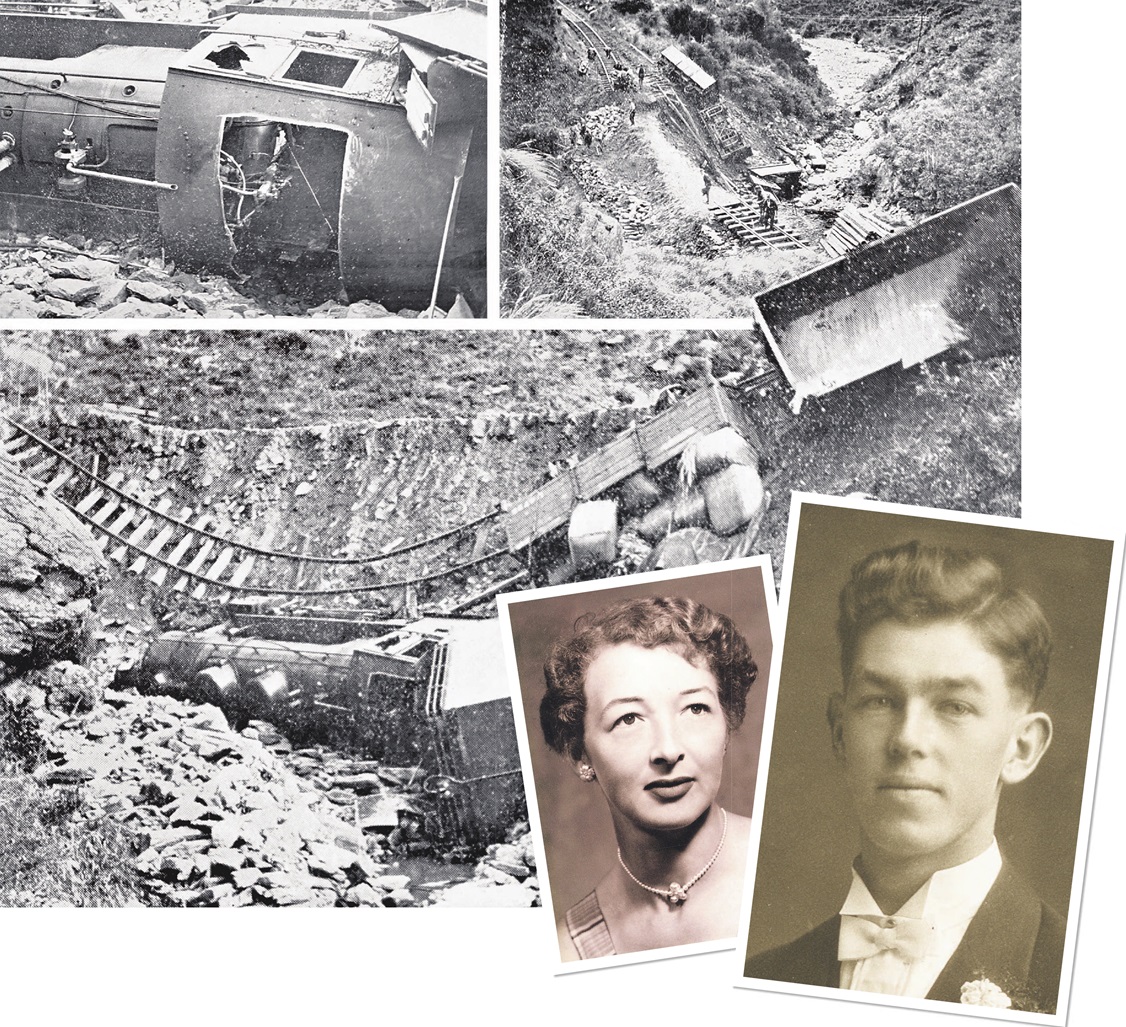

Charles Roy Tuck stares out of one of the few black and white images that remain of him, a confident young man brimming with potential. He has a young family, is showing great potential at work, and has a world of opportunity in front of him.

It is potential that will be cruelly cut short. Another image shows a derailed steam train, Ba552, jolted off its steady course on the night of March 19, 1929 by a track washout.

Underneath it lies NZ Railway locomotive fireman Charles Roy Tuck who, as an in-depth coronial inquest will reveal, has lost his life in unfortunate and possibly avoidable circumstances.

Roy Tuck had not achieved great things, although everything about his character suggests he might well have. But one great thing he had done was be the father of Florence and Charles.

It is a photograph of Florence that brings this story full circle. Although she briefly knew and barely remembered her father, Florence was determined that his life would not be forgotten.

Roy Tuck was an Aussie battler.

Born in Perth in 1902, he was the eldest child of Charles Elliott Tuck — a Dunedin born railway servant — and Bridget Mary Taguer, the daughter of an Irish sea captain.

When Roy was 11-years-old his father, thirsty on a hot day, drank water that — unbeknownst to him — was contaminated. He died soon after.

The devastated family regathered themselves in the wake of the tragedy and Bridget Mary made the difficult decision to leave Perth behind to sail to Dunedin with the assistance of her late husband’s family.

However, arrival in Dunedin in 1913 resulted in the Tuck family being separated: the eldest children, Roy and his sister Winifred, stayed in Dunedin with their grandmother in Caversham, while their mother went to work on a station in Kelso as a housemaid and her youngest two, Evelyn and Frank, moved to the Southland hamlet of Tuturau, staying with other Tuck family members.

The family still have letters written by Roy to his mother from 1914-16. In one letter, in immaculate cursive script, he reports that he has just sat final exams for the year, that he and Winifred were in the forthcoming Sunday School show (she reciting, he in the choir), and that they had been giving the younger children rides in a cart he had made.

"I hope Frank and Evelyn are well and that you will soon be out of hospital and feeling quite well again."

Roy always signed off his letters with "I remain your loving son Roy".

In 1915, Roy was in the St Clair Presbyterian Church junior choir and doing well at school, but the following year he and Winifred moved to Kelso, near Tapanui, where they were reunited with their mother and younger siblings.

Roy vanishes from family history at this point, but reappears in 1920, aged nearly 18, having joined NZ Railways in Invercargill as a cleaner. Being bright and ambitious promotion was not long in coming. In May 1921 he transferred to Dunedin from Wairio as a cleaner and acting fireman. During 1923 Roy worked his way up to full-time fireman and was training to become a second-grade engine driver.

He was also community minded: he became a member of both the Hillside Ambulance Brigade and the No 1 Locomotive Division of St John’s Ambulance in Dunedin, taking first-aid classes on alternate Monday evenings. In a class of 26, Roy had the highest marks.

March 18, 1929, a grim and rainy day, Roy said goodbye to Alma and his children, Florence and Charles, and set off to work at NZR on steam locomotive Ba552, a freight engine, which had recently been refitted with a new higher-pressure boiler and wide firebox, overhauled at the Hillside Workshops.

No-one was better qualified than Roy Tuck for a test run to Omakau: he had qualified as a second-grade engine driver, and he was well respected and competent.

As an NZR fireman, Tuck’s job was to stoke the fire that powered Ba552 as it travelled across Otago.

It was an important job: no fire meant no steam, which meant no passengers or freight making their destination. He also had to keep an eye on the water levels and, in any spare moments, kept an eye on the left hand side of the rail track for any obstacles or impediments.

He, William Pullar (the engine driver) and Cecil Chave (the guard) were in Middlemarch late that afternoon, waiting with foreman Thomas Handisides to take a goods train laden with wool and livestock to Dunedin.

The train was due to leave at 4.56pm but was running about two hours late, in part due to the prevailing weather — it had been lashing down all day. It was dark and the crew were told there was surface flooding at Salisbury, a hamlet near the Wingatui viaduct.

After the driver of train C8 reported the difficulties he had faced in getting through two hours previously, they were cautioned not to attempt it.

The train proceeded to Hindon without mishap, arriving there about 8.55pm. They made inquiries there regarding the condition of the track ahead, and were told that there was water over the line at Salisbury. The driver then took the train on to Parera, where he stopped, and his previous information was confirmed.

Eventually, about 10pm, they were under way from Parera, headlight brightly gleaming, all crew on the lookout, and the driver crawling at a modest 4-5 miles per hour (6-8kmh).

As they approached the culvert where they had been warned of flooding, Pullar slowed the train to almost a full stop, intending to check the track before proceeding further.

Spotting a washout he pulled the brake on but it was too late: there was only thin air where earth and track was meant to be and, with a graunch and a clash, Ba552 dropped straight down into the swollen Taioma stream.

There the engine lay on its side, almost instantly filling with 3 feet of water. Pullar and Chave were unscathed and out of the train, but they could not see nor hear Tuck.

They started searching for him, eventually accompanied by Handisides, who had switched to a different train, and other railwaymen, but could find no trace.

Where Tuck was standing, he too should have been thrown clear of the train after it tilted and crashed, but instead, his foot became wedged under a footplate outside the cabin.

Unable to free himself, Tuck was crushed as Ba552 tipped over on its side. Chave thought he had felt Tuck’s leg in the water but he and Pullar were unable to see him in the bleakness of the stormy night. Regardless if Chave had touched Tuck or not, there was absolutely nothing his colleagues could have done for him in the circumstances.

Tuck was just 26 when he died. He is buried in Andersons Bay cemetery. Florence was just 2, Charles a baby just 4 months old.

His widow, Alma, remained in Dunedin for many years and lived until she was 98 years old.

Then, as now, the local newspapers reported extensively on coronial inquests.

Roy Tuck’s death was adjudged by Special Magistrate Bartholomew to be a terrible accident, his death having been caused by being crushed by his train engine.

That was the easy bit: a substantial amount of the inquest’s time was taken up in trying to work out if the train should have been on the tracks at all that night — and, if the trip had to go ahead, whether it would have been wiser to have had a jigger cart preceding them to look out for any issues on the track.

"The coroner stated that every care seemed to have been taken and the crew of the train had proceeded with due circumspection," the Evening Star reported.

"Absolute security could not be guaranteed and all that could be done was to take reasonable precaution."

The Otago Daily Times added that if the train had been travelling by daylight conditions might have been safer, a self-evident statement but one that leaves unanswered the question whether disaster could have been avoided if the train had been running to time as scheduled.

And that might well have been that for the story of Roy Tuck, but for the efforts of his daughter Florence.

"I think my mother did not want her father to be forgotten," Florence’s daughter Deborah Ford, says.

"The plaque was something that my mother completed much later in her life. Mum was 79. I thought Mum was amazing, and she was very proud of this plaque, and it brought her some final closure.

"I think a lot about my grandfather and the man he was. I am immensely proud of him too. I often reflect on who my grandfather was, and his characteristics. I have read, work mates said he had a ‘cheery’ disposition. Family would have been deeply affected by his loss and did not speak of the tragedy: it was just too painful.

"When I was younger, I learned that my nana dressed in black for four years after Roy’s death. When someone suggested she change her colour, she switched to brown. My nana would have been totally heartbroken."

Florence was a primary school teacher and lived in North Canterbury with her husband and three children, but she kept being drawn back to Otago, and to her father’s story.

"My mother wanted to investigate more things about the Taieri Gorge, then Mum met some of the rail enthusiasts and must have got talking," Ford says.

"Mum had told me she would like to have some sort of plaque up at the gorge to honour her late father, and with that it became her mission around 2005. (Husband) Graeme and I often accompanied Mum on the train through the Taieri Gorge Railway."

Fortunately for Florence, her push to build a memorial for her father coincided with increased interest in wider society about history in general and family history specifically. Where, just a few years before, her inquiries may have met with blank stares and general disinterest, she found people wanted to help her as much as they possibly could.

"By making the right phone call to the right organisation we got an incredible result," Ford says.

"A lot of people are very passionate and helpful, and it is wonderful to see there are so many rail enthusiasts."

In 2005, a small metal plaque was placed by Florence and a rail enthusiast group beside the Salisbury-Taioma stretch of the line, about 300m from the point where it was thought Ba552 left the rails.

"Each time we went, we would look out for the white post with the plaque on it, and each time, it was getting a little rustier and weather beaten. By 2017, the time had come for me to do something about this," Ford says.

She began by restoring her grandfather’s grave and headstone, a job completed just before Florence died in 2018.

"I left it for a couple of years and then I thought, I don’t want to be 80 when I’m doing this, even though I will still be on the train when I’m 80.

"I just love the train journey out there. It is beautiful, the incredible landscape and stunning viaducts."

The bid to build a commemorative memorial to Roy Tuck involved several trips along the Taieri Gorge Railway. Ford began by approaching the Dunedin City Council and Dunedin Railways, which were immediately supportive of building a more permanent memorial. Likewise, people approached to work on the memorial embraced what Ford was trying to do.

"Nobody literally said no, it was another example of everyone being in the right place at the right time. It is a commemorative memorial. We wanted it to last out in the environment."

The memorial cairn is built from local schist rock, and a capstone. Beside the cairn is a 1920s-era fireman’s shovel, framed by railway iron, to symbolise the job Tuck was doing, and as a reminder of the perils that the weather can pose.

There is also now a memorial to Tuck in the Dunedin Railways ticket office.

"The memorial is now on their itinerary, they speak about it when the train goes through," Ford said.

"Dunedin Railways said on the day of the memorial they were very proud, and they also said that we had created history that day as well."

There is now also a replica of the steam engine locomotive’s number plate, Ba552, gifted by Graeme Ford, which will remain in the family through the generations of the Tuck descendants.

There is one chapter left to write in the Roy Tuck story, one mystery that remains unsolved.

After his death his distraught colleagues from NZ Railways instituted the Charles Tuck Memorial Cup, a prize awarded for the winner of an annual competition between the city’s ambulance brigades.

The first event was in October 1929 — the record is silent whether Alma and the children were there, but at the prizegiving an enlarged, framed photograph of Roy was unveiled.

Newspaper records of the cup fall silent in 1936, when the Roslyn squad beat the Forbury squad by three points to claim the trophy.

Ford has been on a quest to find the cup or at least learn of its fate. Archives have not shed any light on the matter; discouragingly, engraving firms have told her that old trophies tended to be thrown out if unclaimed.

"The cup itself, because of what happened, would have been a very, very important cup to the generation that were working there at the time, and his colleagues, workmates, and the Ambulance Brigade, they would have treasured that."