Brilliant surgeon and medical pioneer Doug Jolly was born in Cromwell, in 1904, the second son of the local storekeeper. He and several brothers were educated at Otago Boys’ High School and, in 1924, he entered Otago University’s medical school. Jolly chose to specialise in surgery and left for London to qualify for a fellowship at the Royal College of Surgeons. He had not quite completed these studies when, in mid-1936, the Spanish Civil War broke out — a brutal rehearsal for World War 2. Volunteers from more than 50 countries, including New Zealand, travelled to Spain to support its democratically elected government. They included medical volunteers who were flung, with minimal training, into the first war in history to be dominated by aerial bombing.

Jolly, after just four months’ service in Spain, now held the post of chief surgeon in the XIth International Brigade and had been promoted to captain, the same rank his father held in World War One. His hospital, in a large villa on the Madrid-Valencia highway, was shared with two other surgical teams and included veterans of the British medical unit based at Granen the year before. One of them, Archie Cochrane, believed that Bethune’s blood delivery service from Madrid represented "perhaps the most significant advance" to frontline medical services since those early days. Just as Jolly and other surgeons were siting their operating theatres as close as possible to the front line, so Bethune had found a system for providing them with vital supplies of tested and classified blood. Recently renamed the Canadian-Spanish Blood Transfusion Institute, it could now deliver blood to 100 hospitals and smaller casualty clearing stations along a battlefront extending 1000km east of Madrid. The Guadalajara field hospital had a refrigerator specifically for storing donated blood, and another of its doctors, Reg Saxton, had developed expertise in administering transfusions and was recruiting local donors. Up to 100 transfusions would be given daily during the forthcoming battle.

The Guadalajara region was still subject to Madrid’s dire "nine months of winter", and the Nationalist advance was made through snow and sleet, conditions which proved greatly to the advantage of the Republican defenders. Frozen roads and poor visibility caused the fleets of Fiat armoured vehicles to stall in an immovable bloc, making them easy targets for fighter planes and bombers. For once the Republican forces enjoyed superiority in the air since by good fortune their aircraft could take off from an all-weather concrete runway while the Nationalists’ air support sat on the ground on drenched grass airfields. In addition, almost 300 light and manoeuvrable T-26 tanks arrived from the Soviet Union in time to be used, with great success, by the Republican forces. Mussolini’s troops were soon forced into a chaotic and humiliating retreat, and for the first time in the civil war the Republican government and its supporters could realistically envisage ultimate victory.

Nevertheless, huge numbers of wounded continued to arrive at the frontline hospitals, often beyond saving after spending several agonising days in sub-zero conditions. Of the more than 3000 casualties brought into Jolly’s field hospital, many were suffering from frostbite. They included large numbers of Italian prisoners and deserters. To the surprise of nurse Penny Phelps, these were "not Fascist bully-boys, but young conscripts from the Italian countryside".

"Don’t believe the stories that are current that all Fascists, prisoners or wounded, are shot forthwith," Jolly told his friends by mail.

"I have operated on a number of Italian Fascists."

His insistence, at Guadalajara and other battlefronts, on treating enemy wounded on the same basis as other patients brought him into conflict with more ideologically purist colleagues. A Czech doctor, Franz Kriegel, noticed that Jolly labelled arriving casualties in order of the urgency of their condition and operated on them accordingly. First in line was a prisoner of war. Kriegel was outraged at giving this enemy combatant precedence over severely wounded Republican troops, but Jolly stood his ground.

"The reasons that brought me here are the same reasons which will make me operate on that prisoner first; because he is in the most urgent need of salvation. And you can say what you like, and if you continue, I’m going home."

Kriegel out-ranked Jolly, but he apparently tolerated this insubordination and made no further objection to his fixed practice of treating patients regardless of their uniform and insignia.

"I spoke with an Italian prisoner who was a stretcher-bearer in the Italian Army ... He told me that their hospitals were far behind the lines, and that many abdominal cases died without operation."

This specific observation is borne out when the organisation of the opposing armies’ medical services is compared. The Nationalists relied more heavily on older, WW1-era models of treatment provision, and these proved less effective than the more innovative and improvisatory Republican systems at dealing with vast numbers of injured along a poorly-roaded battlefront.

However, the equipment supplied to the Nationalist hospitals, like the weaponry available to their troops, generally surpassed anything available on the Republican side. Among the very large quantities of war materiel captured from the retreating Italians at Guadalajara, and immediately put to use by their victors, was an entire tented field hospital whose heat-retaining double walls and other advanced features greatly impressed Jolly. In the cruder, single-walled tents available to him, "it was wholly impossible to subdue the slight glow at night which might attract the attention of a prowling aeroplane".

Furthermore, in the Republican tented hospitals heating could not be controlled and "the tragic plight of the wounded during the winter months can be imagined; in the summer it was almost impossible to work inside such tents or to maintain the progress of the wounded after operation".

The exhaust steam from the autoclaves installed in trucks could be directed through pipes and radiators to heat tented operating theatres but more dangerous methods using highly flammable fuels were employed if necessary.

"The best method of initially heating an operating room," Jolly found, "is to burn alcohol in a large flat dish, but the temperature should be maintained by some cheaper method".

These improvised heating systems were installed by the equipo’s mechanic, John Kozar, a tough and swarthy former seaman from Canada, of mixed Czech and Lakota Native American heritage. Jolly knew him as Topsy and remembered him as "indefatigable and well beloved by us all ... Brave as a lion".

Doug Jolly spent two years in frontline field hospitals during the civil war, until he and all other foreign volunteers were ordered to withdraw in late 1938. He then condensed his unique experience of medical service in modern warfare into a remarkable manual, Field Surgery in Total War. It became an instant bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic and 20 years later was still regarded as indispensable by surgeons in the Korean and Vietnam Wars. In 1940 Jolly enlisted in Britain’s Royal Army Medical Corps and served throughout World War 2, in North Africa and Italy. He received a military OBE and gained the rank of lieutenant-colonel. In peacetime, he became chief medical officer of Britain’s largest orthopaedic hospital. Since his death, in 1983, the storekeeper’s son from Cromwell has been gaining international recognition as a significant innovator of trauma surgery, having developed systems for emergency treatment that are practised by organisations such as the International Red Cross and Doctors Without Borders.

The book

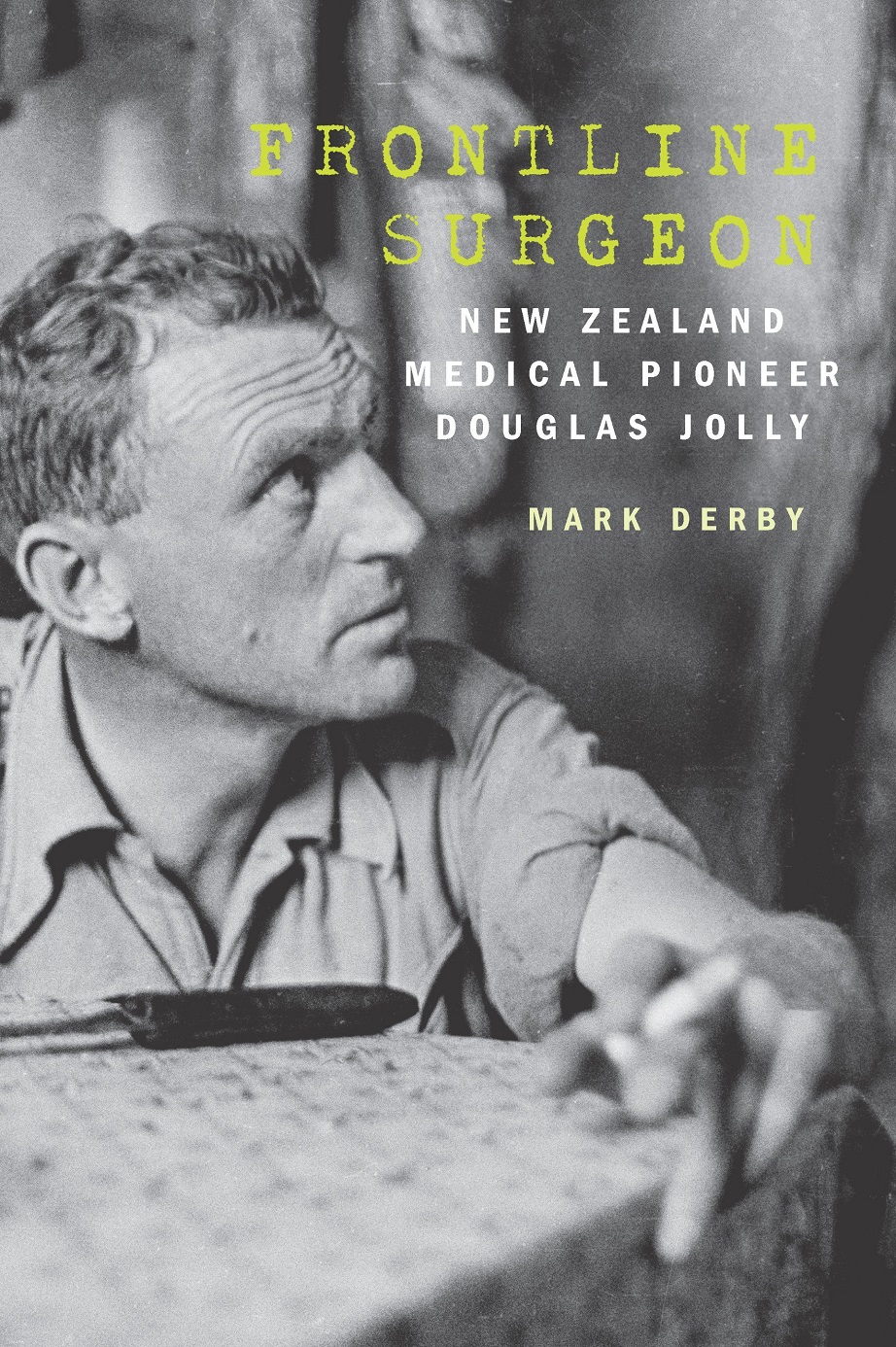

Extracted with permission from Frontline Surgeon: New Zealand medical pioneer Douglas Jolly, by Mark Derby, published by Massey University Press, July 2024, RRP $45