Until now, much of the Māori history of the West Coast has been fragmentary. Ironic, given what the author of new book Poutini, Paul Madgwick, says is a region "rich in storytelling".

For Madgwick (Ngāti Māhaki, Ngāi Tahu), pulling together Poutini: The Ngāi Tahu History of the West Coast built on a lifetime of research. His Ngāi Tahu chronicle of the West Coast draws these strands of history into one place, with the voice of the iwi and its predecessors woven into a narrative along with historic and contemporary photographs, detailed maps and whakapapa.

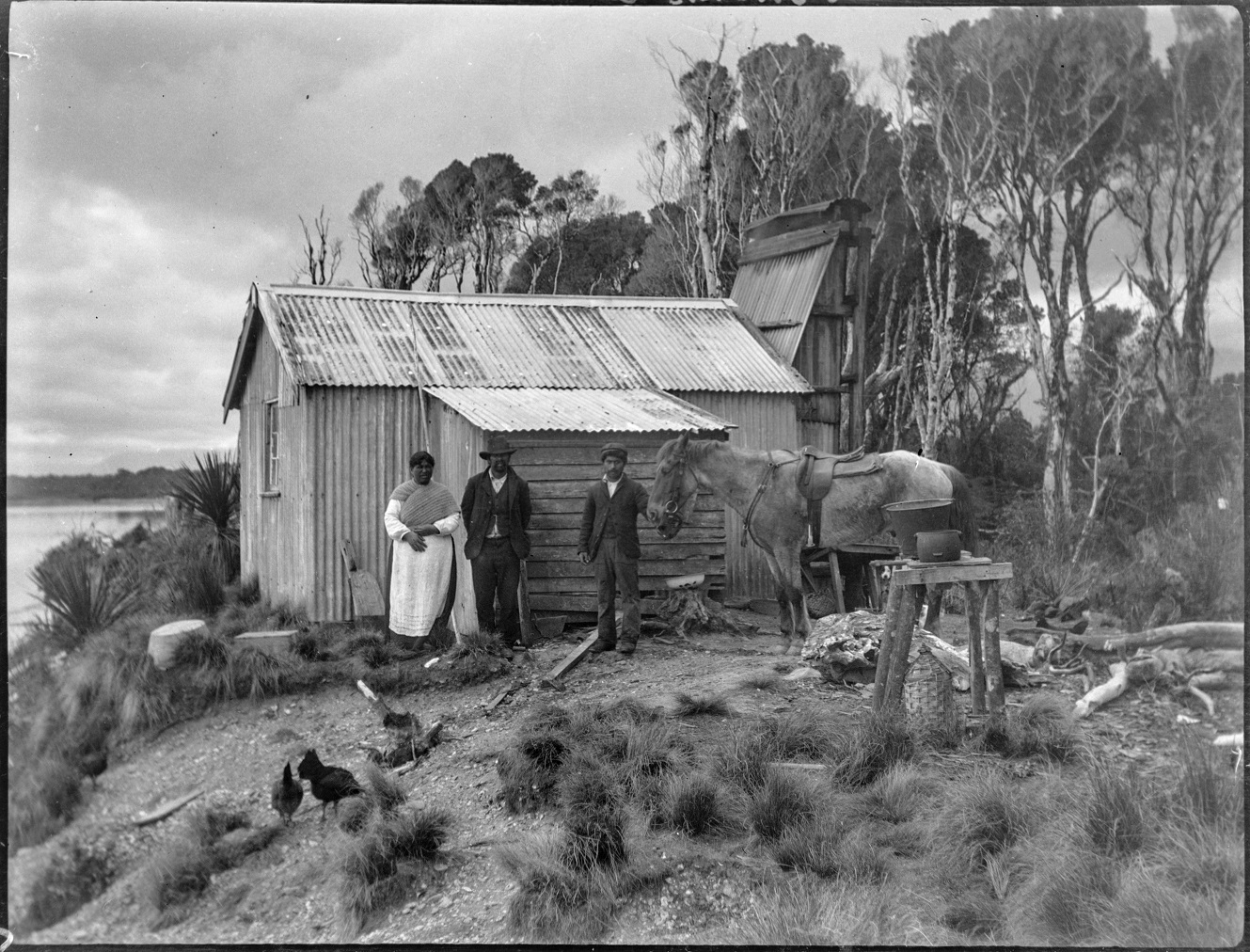

This was a place of bush and water:

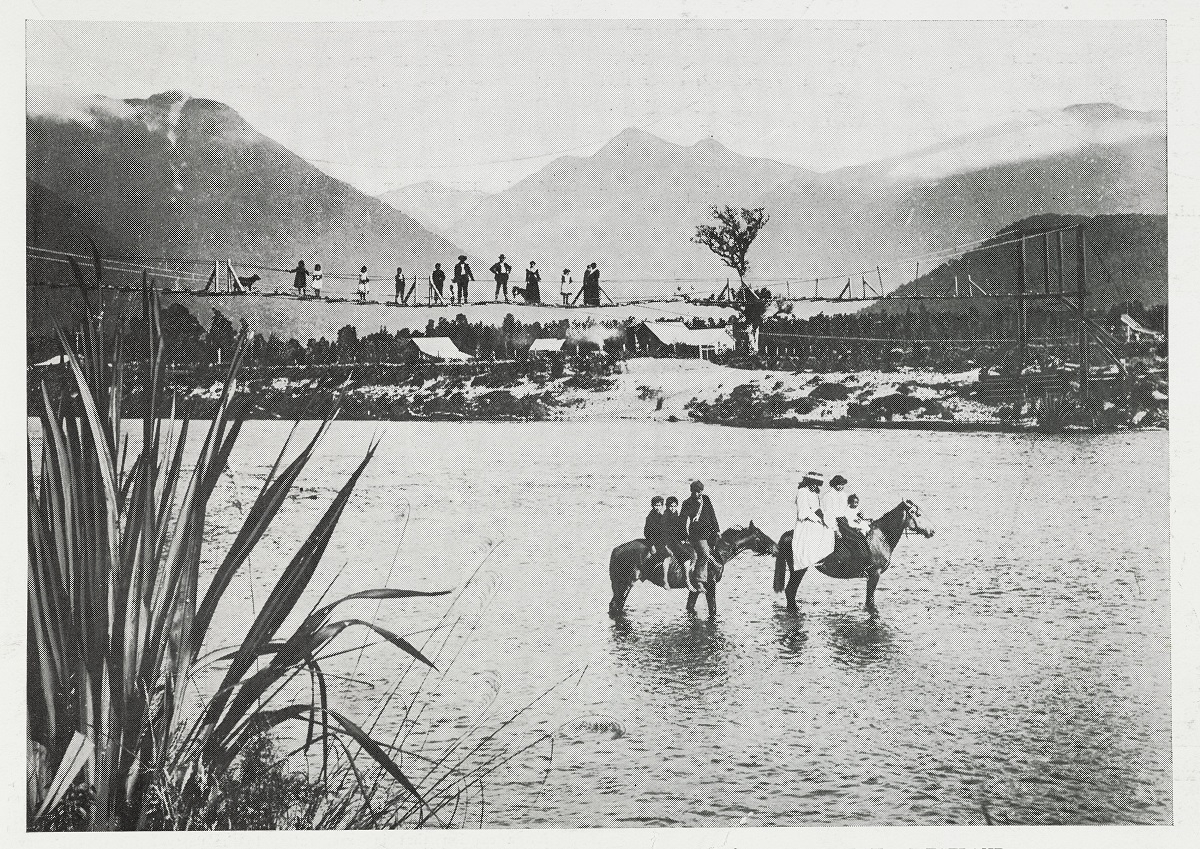

The pre-European West Coast was no picnic. Poutini Ngāi Tahu, well accustomed to the vagaries of the weather and the landscape, knew it as a land that teemed with fish and birdlife, but Pākehā were vastly ill-equipped to survive on their own in this unforgiving, out of the way region. It was, as Ihāia Tainui once said, no place for white men.

Early Pākehā explorers and surveyors learned quickly that local Māori "held the key" to them combating the wilderness.

Access was by foot over treacherous routes, and the added threat of floods with every rain cloud meant the journey was invariably much longer than travellers could carry provisions for. This inevitably led them, often half-starved, to seek out the nearest pā.

They relied on the generosity of Poutini people for their very survival.

As a keen local historian, born in Hokitika, chairman of Te Rūnanga o Makaawhio for two decades and editor of the Greymouth Star, the planets had always been aligning that he would be the one to write Poutini.

"I was giving a talk about Māori history on the Tai Poutini to the West Coast District Health Board," he says. "They wanted to know more about this place, and so I talked for about half an hour. Afterwards, one of the doctors came up to me and said that he was really absorbed by that history, and wanted to know what my legacy plan was for that.

"I said, ‘legacy plan?’. He said, ‘well, if you turn up your toes, who’s going to be the keeper of these stories? Or have you written it all down perhaps?’. And, of course, I hadn’t. But it set me thinking. So, I went home and talked about it, and the next week I started on Poutini.

"It was the kick that was needed. Otherwise, it could have been waiting there until my old age."

Madgwick had more than just an inkling of how much work such a comprehensive undertaking might be. In 1992, his book Aotea: A History of the South Westland Māori, was published.

"Aotea was my big project in my twenties. I loved it, and it had a really good response and people wanted to know more. It opened some minds because there hadn’t been anything previously written about Māori history on the West Coast, not in one place.

"At the time when I was gathering the material for Aotea, I came across all sorts of archival material related to Māori all over the West Coast, not just South Westland. It quickly dawned on me that our histories were so entwined, of Ngāti Māhaki and Ngāti Waewae and Poutini Ngāi Tahu, that because we all come from the same tree there really ought to be a single history to bring it all together."

At one stage, Madgwick had a library full of archival material. But now Poutini is finished, that information has been "relegated to the garage".

Researching, writing and sourcing photographs and other illustrations for a volume of such wide-ranging stories takes some doing. The 528-page book is full of images and maps, and features detailed appendices including a timeline, an explanation of place names, and genealogy.

But rather than feeling overawed by the size of his undertaking, Madgwick says he first took time to chart the landscape of where it was going to go.

"Once I was under way with it, it became fairly easy. I plotted how I was going to structure the book into different kaupapa. I intentionally wrote this so that each chapter ought to be able to stand alone, so you should be able to pick up anywhere and find something interesting that makes sense.

"But every book has to have a starting point. And so I started with the pūrākau, the legends, the early stories. But that doesn’t mean you have to start on page one."

Writing began at the end of 2017 and was completed in 2021, always keeping in mind his structure and the need for the plan to be flexible.

"There was always the motivation to keep going on to the next chapter. I would get really excited about finishing that chapter and getting on to another one. So, I’d have my own little celebration when I’d finished each chapter and ticked them off.

In the foreword to Poutini, Te Pae Kōrako (Ngāi Tahu Archive Advisory Committee) chairman Sir Tipene O’Regan says Madgwick, a significant Ngāi Tahu leader, has "articulated, indeed asserted, the character and presence of Ngāti Māhaki and Makāwhio".

Drawing from sources such as tipuna manuscripts, government archives, Pākehā historical narratives, surveyors’ notebooks and newspapers, Poutini is "part of a growing stable of Ngāi Tahu histories written by Ngāi Tahu people", O’Regan says.

"Owning and controlling our own knowledge base is at the heart of our capacity to disseminate that heritage. This does not mean that our knowledge base is exclusively ours and should not be shared with others. But we are the primary proprietors of our own story, our own heritage and our own cultural identity."

Poutini embodies the spirit of Ngāi Tahu’s rangatiratanga, O’Regan says.

Asking an author about the favourite parts of their book is like asking how long is a piece of string.

Madgwick mulls the question and settles on his chapter three, "Ngā Papakāinga — Settlement", a vast work in itself, with 187 pages covering events from the north to the far south of Te Tai Poutini.

"I enjoyed Papakāinga, I enjoyed pulling together the stories from each of the pā and I did that geographically, working my way down the Coast, from Westport right down to Whakatipu Waitai/Martins Bay.

Madgwick tells the story of a tangihanga for Pātene (Jacob) Hākopa at the small St Peter’s church at Jacob’s River in South Westland in July 1941. Vicar Sam Woods was flown to Makāwhio, as remembered by his wife, Sybil:

We were soon flying over the Paringa and began circling low over the bed of Jacob’s River looking for a possible landing place. There were no airstrips in those remote parts but Bert Mercer was adept at landing his little plane in the most unlikely place. Spotting a stretch of dry riverbed relatively free of big boulders he nosed the joystick forward. We held everything including our breath, and came to a safe if bone-shaking halt ... By the time we reached the house I felt that a strong cup of tea and a beefy sandwich were a ‘must’. However I learned that first I must pay my respects to the dead chief ... Old Jacob looked serene, dignified and at peace in his mat-draped coffin. After greeting the other mourners with the traditional ‘hongi’ we were at last refreshed with a substantial tea.

The next chapter, "Te Oranga o te Pā — Life in the Village", is also a favourite, particularly the section on manaakitanga.

"It’s about daily life and hospitality," Madgwick says. "About how life here was then. It was no picnic. As Ihāia Tainui said when the Europeans were first coming in, looking for gold and their exploration and the like, this is ‘no place for white men’.

"It was too wet for a white man, and that was perfectly true in those early days, because the place was so full of bush. Today there’s still a lot of bush, but back then it was just bush and water."

Explorer Richard Sherrin was among those who praised local Māori for their kindness and loyalty to Pākehā in the 1860s:

Natives are the best men to take with you when travelling ... they stand like a rock in the water foaming around them; they manage their canoes with a boldness and skill quite astonishing; they will find food when you can discover not a trace; they will light a fire when all your matches and powder are wet, by the friction of the kaikomako wood; they will watch over you like a mother over her children, to prevent your ‘coming to grief’, they will be content with a small quantity of food when food is scarce, and have, most of them, presence of mind in danger, and are free from cowardice when death stares them in the face.

Madgwick also makes special mention of the appendices.

"Place names were also one of my favourite parts. I’ve worked with the Kā Huru Manu (Ngāi Tahu Cultural Mapping Project) for many years, recovering and restoring our names. And pulling them together into this one place for that has been a big job, in parallel with doing Poutini."

Writing a book can take years off your life, especially if it is as large and all-encompassing as Poutini. But it is also strangely addictive.

Is there another book on the way? Was there anything left in the research cupboard which might make a separate story?

"Once I resolved to do a West Coast Māori history, that was my sole focus. So, I attacked it from every angle. It’s not to say this is the complete history of Māori on the Tai Poutini, I wouldn’t be so arrogant as to say that, but it’s a comprehensive history.

"I thought once of writing something longer, starting with a short story, of that transition period between te ao Māori and the arrival of the Pākehā, but then I decided I’m not a novelist.

"Who knows. Someone might have some old whakapapa books, which were common up until the 20th century, when that generation that first learned how to write wrote down the whakapapa and started recording some of the stories."

Or he might finally finish a writing project he began before he was even a teenager.

Madgwick’s mother was Poutini Ngāi Tahu and his father was a Pākehā West Coaster of Irish and English heritage, from old goldmining stock.

"When I was 11, I started writing my first history book, about the Rimu-Woodstock goldfield. I’d love to finish that but it’ll have a more limited audience. But I promised myself I would do it.

"The old people I used to go around and pester for their stories and photos then would say to me, ‘make sure you write this all down before I die’. They’ve all died. But I’ve still got all that."

Poutini was unveiled for Poutini Ngāi Tahu at the Pounamu Pathway in Māwhera last month. A public launch is being held on Wednesday at the Regent Theatre in Hokitika.

Madgwick says the book has been receiving good feedback from Māori, Māori historians and West Coast historians more broadly.

"You asked me earlier, why this book? We’ve seen some bits and pieces of our history, of our modern history, that have been written online and in the likes by Pākehā, and basically they’re just wrong.

"So, rather than trying to correct that, I really wanted to write our own history, rather than have it misinterpreted or misrepresented."

The book

• Poutini: The Ngāi Tahu History of the West Coast is published by Oratia Books and Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu.