To call Sir Vincent O’Sullivan a writer would be selling his career very short. He was arguably the country’s foremost literary polymath.

Yet despite all the accolades and recognition, his friends say he was almost under-appreciated.

And he was a man who had many friends.

In compiling this obituary, one was struck by the sheer number of people who came out of the woodwork to express their admiration.

No wonder: he was one of only two writers — the other being Janet Frame — to have won every major category in the New Zealand Book Awards (poetry, fiction, and non-fiction).

Sir Vincent, who died in Dunedin on April 28, aged 86, was not only a disciplined academic and researcher, but also a very earthy poet and prose stylist, who understood local history and vernacular.

He was also a trenchant reviewer who spoke his mind and did not suffer fools gladly.

He spent his final years in Dunedin and remained prolific to the very end — Still Is, his last collection of poetry, was finished a few weeks before his death and launched in Wellington yesterday.

The anthology brings his career full circle; his first major published work was poetry collection Our Burning Time in 1965.

Born in Auckland on September 28, 1937, Sir Vincent combined an academic career with that of a prolific writer and editor.

He attended St Joseph's School in Grey Lynn, and Sacred Heart College, and later graduated from the University of Auckland with a bachelor of arts degree in 1959 and a master’s of arts with first-class honours the next year.

He spent a year at Oxford University, and lectured in English at Victoria and Waikato universities, before becoming literary editor of the New Zealand Listener from 1979 to 1980.

Six years of fellowships at New Zealand and Australian universities followed, interrupted by a year as resident playwright of Wellington's Downstage Theatre where the first of his several stage plays was performed in 1983.

Te Herenga Waka University Press publisher Fergus Barrowman met Sir Vincent for the first time in 1983; when Sir Vincent was working on his first play Shuriken.

"I found him quite intimidating; he was kind of a star at the time. But as I got to know him, he was a very kind and funny person.

"He was a really gifted writer across all of the genres. Also, he was a dedicated scholar. He brought a real openness — the way he could synthesise things was remarkable."

The absolute essence of Sir Vincent’s talent was most present in the poetry, Mr Barrowman said.

"It was the musicality of his language; the way he could mix the vernacular with the educated. He had a very dark sense of humour. The very best of his poems will create a core canon.

"But if you look more widely, Shuriken is a terrific piece of theatre and was very important in bringing the story about the massacre of Japanese prisoners of war at the camp in Featherstone back into the public consciousness.

"There are the three novels, all of which were terrific. And biographies of Ralph Hotere and John Mulgan which get the measure of the men.

Mr Barrowman said he was in awe of Sir Vincent’s "focus on accuracy".

Historian Redmer Yska remembered Sir Vincent’s generosity.

"When I got to know Sir Vincent in 2012, I saw his collegiality and generosity first hand.

"Vince told me that my findings were important and that I must publish them. He insisted on writing the foreword to the book that became A Strange Beautiful Excitement, Katherine Mansfield’s Wellington, 1888-1908. When he'd visit Wellington, I'd report, over coffee, on my latest archival finds, and saw his salty, iconoclastic sense of humour.

"I told him about a police file I'd found from 1900. It had letters from Harold Beauchamp, Mansfield’s father, complaining about children in the street outside the family mansion at 75 Tinakori Rd, the slum children from Saunders Lane featured in her story The Garden Party.

"I'll never forget the grin on Vince's face when I told him about Harold's complaint that the children had defecated on his steps, and run away."

Author and friend Dame Fiona Kidman met Sir Vincent nearly 50 years ago.

"I was in awe of him, which looking back was a bit silly because Vincent never big-noted or tried to make people feel lesser in any way.

"It was a few years before I really got close to Vincent, and then I think it was by dint of my own work beginning to make its mark, he anthologised some of my stories.

"We got into a literary stoush or two, on the same side, and a friendship was born that never faltered in all the years to come. We were in the thick of it in the Springbok tour too, that helped cement the friendship."

Sir Vincent concentrated mainly on poetry in his earlier years.

But in the 1970s, he turned increasingly to short stories, which have been published in seven collections, starting with The Boy, The Bridge, The River.

His novel Let the River Stand won the Montana Book Award in 1994.

His other novels Miracle: A Romance (1976) and All This By Chance (2018) were also acclaimed: Stuff critic Nicholas Reid praised Sir Vincent’s acumen for portraying "the hold that the past has over us, how the past shapes us whether we like it or not, and how lethal it can be to pretend uncomfortable parts of the past never happened".

He edited eight volumes of writing by Katherine Mansfield, and several anthologies of New Zealand poetry, and wrote studies of James K. Baxter, Ralph Hotere and John Mulgan.

He also wrote nine plays and 10 librettos; took up residencies and fellowships at universities in New Zealand and Australia and mentored dozens of young writers.

Dame Fiona said Sir Vincent was always "witty".

"If I could have written down every funny thing he had said I would have a book as full as a volume of Katherine Mansfield letters.

"But beneath that was a deep seriousness, someone who listened, not just liked being listened to, and cared about his friends, and talked through problems with them. I'd describe it as an underlying tenderness.

"He loved his family, adored his grandchildren, liked dogs. But he didn't suffer fools, or double standards. And he would say so. Politics absorbed him. He lacked pretension of any kind. He loved rugby too."

Dame Fiona described him as a "commanding" figure.

"But it was not just that he covered such a wide range of genres; he brought excellence to everything he did.

"He understood ‘the common man', which sounds like a stuffy thing to say, but it was true, if you look back to the Butcher & Co poems [1977] it shines there at the very beginning, knowing what made everyday people tick. I think he brought this to bear in his poems and biographies most of all.

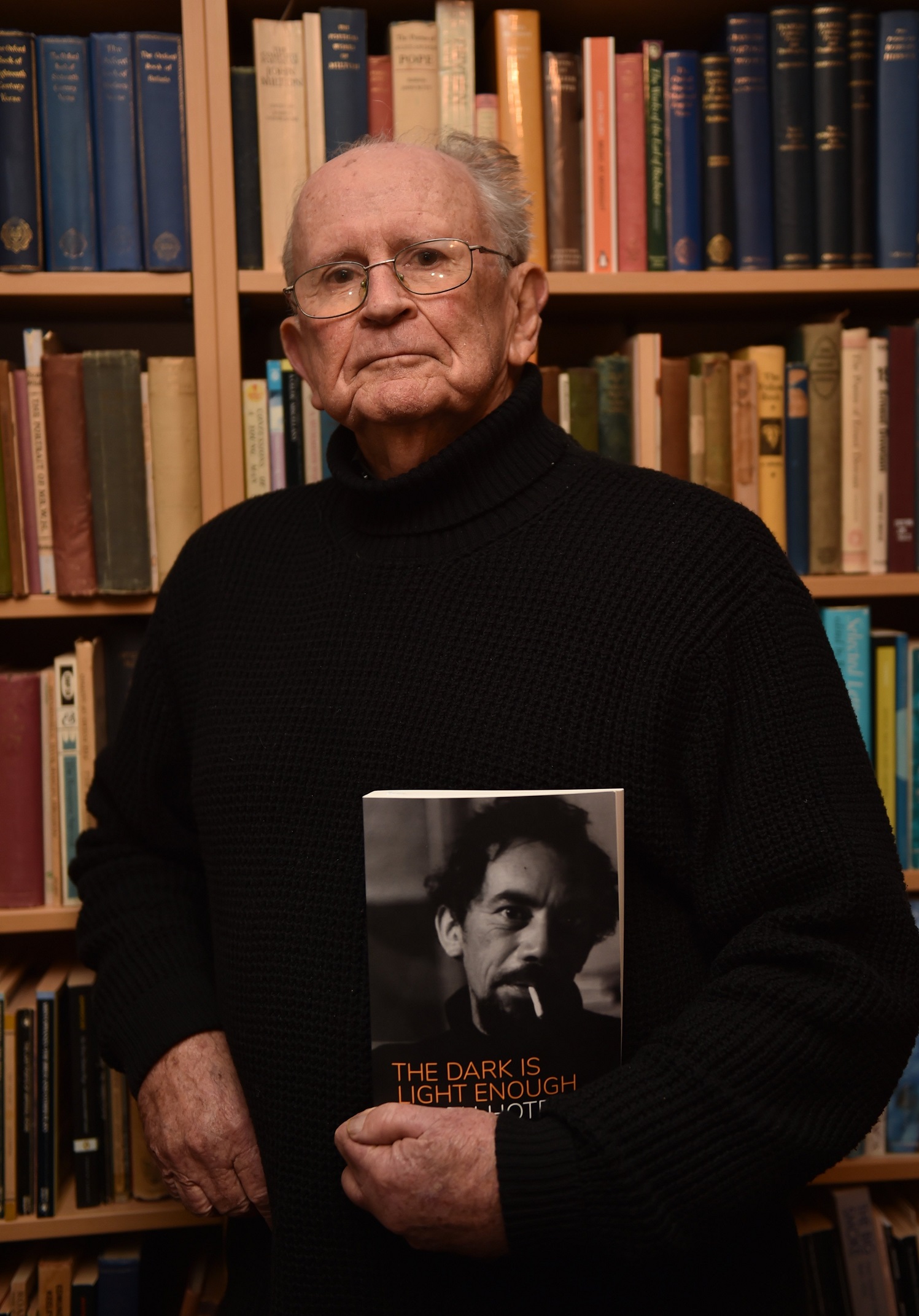

"The Hotere bio, The Dark is Light Enough is one that I think could only have been written by him. He understood the art, and he understood the man.

The accolades kept coming throughout his career.

In the 2000 Queen’s Birthday Honours, he was appointed a Distinguished Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit, for services to literature.

However, he accepted the change in December 2021.

Before he died he asked that the following be noted

"Some of my friends asked me why, as an old time republican, I accepted a knighthood a few years ago. It’s not the easiest thing to wave two flags at once.

"One reason was the obvious one, of it being conferred by the country I am part of and that has given me so much over the years, and more so for my family’s sake. My father, Tim, was born in 1897 — several months after his father, another Tim, died while his mother was pregnant. My grandfather had been born a few years after the Great Famine in Tralee. It was principally for his sake, and the satisfying sense of historical irony, that I accepted the knighthood'.

He was the country’s Poet Laureate in 2013.

Sir Vincent spent his last 12 years in Dunedin, writing plays, poems and librettos and reviewing for major publications in his spare time.

Many of his later poems, such as Just Finding the Day, pay tribute to the relaxed and warm lifestyle he cultivated in Dunedin.

Dunedin writer and friend Philip Temple told the Otago Daily Times Sir Vincent was a "remarkable" literary critic, who "encouraged those who would have otherwise been ignored by the Wellington establishment".

"He would operate quite a bit behind the scenes.

"He had quite an acerbic touch at times.

"He was a serious writer — he was dedicated to the craft and the idea of excellence, and he could be very critical of what he saw as inferior writing.

"To me, he was one of those who kept up the standard."

He is survived by his wife Helen, and his children from his first marriage to Tui Rererangi Walsh, Dominic and Deirdre, as well as his grandchildren Lucy, Xavier, Joey, Tui Rererangi and Delphi

Deirdre described Sir Vincent as an "affectionate" father.

"He always had an innate curiosity for things and an incredible memory and a huge range of interests — and those things obviously came across in his writing but just a much in his everyday life.

"But he was also a very pragmatic person — he viewed his writing much in the same way a good builder would view their work.

"He knew he was a good writer, but he didn't necessarily view his profession as more worthy than others. He certainly never used his titles and was just Vince to most people."

Deirdre said for a private person, Sir Vincent had "many friends" from school days to more recent times.

"I think he was part of a New Zealand where everyone did connect with everyone else, whether you were academics or labourers or sportspeople."

Picking a favourite work proved difficult for Deirdre, but she was particularly moved by his collaboration with composer Ross Harris, Requiem for the Fallen, which was produced to mark the centenary of World War 1.

She also enjoyed the personal resonance of his 1969 poetry collection Revenants.

"He was such a perfectionist that he was often critical of his own work — especially this early work — but I loved the language and settings of those poems."

Not having Sir Vincent around meant she would miss his stories — and his jokes.

"He was very engaged ... I think he even surprised himself." — Matthew Littlewood