(Brett McDowell Gallery)

The late Martin Thompson was one of the unforgettable characters of the New Zealand art scene.

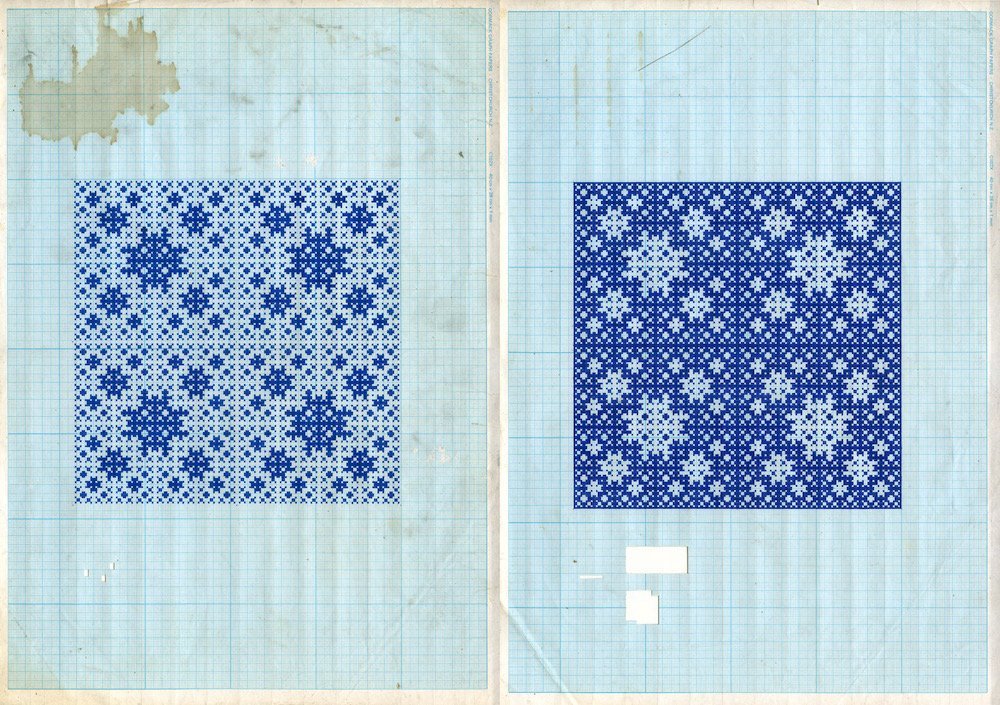

Thompson’s work was the result of converting complex mathematics into grid-like geometric abstract structures. The obsessive nature of his art, using specific grades and shades of ink pen on grid paper, matched the artist’s personality, and also matched the eccentricity of his artistic practice. He could often be seen at Wellington and Dunedin cafes working at his grids, seemingly oblivious to his surroundings.

Eighteen months after Thompson’s death, Brett McDowell Gallery is displaying a selection of work recently rediscovered by the artist’s brother. The pieces, many of them early work from the 1990s, display all of the artist’s trademarks: matched positive and negative grids, meticulous pen-work to record the recursive, mosaic-like structures, and the artist’s quirky working methods. The paper is often stained by coffee cups, with tiny sections of unused grid cut out to repair mistakes in the pattern, and there is a gentle haphazard grubbiness to the paper which adds to the charm.

Like all the greatest art, what we see is a mere reflection of the perfect patterns that Thompson wove in his head. The stained nature of the finished works simply adds a human touch to the austere yet beautiful mathematical precision.

(Olga Gallery)

There is a dichotomy in Anya Sinclair’s acrylics that is clearly shown in her current exhibition at Olga Gallery.

On the one hand, Sinclair produces lush, limpid riverine scenes, depths of jungle and bush overhanging dark waters and seemingly steeped in humidity and mist. Alongside these, she produces almost childlike flower blooms, sketched with painterly freedom. The two styles are so much in opposition that it is difficult to directly compare them.

My own personal taste is for the river scenes. Created using images from the internet as a guide, Sinclair effectively captures the steaming South American forest in works such as River of January (the title, which translates into Portuguese as Rio de Janeiro, gives a clue to the original river’s location). The flower works also have a charm, but the sketch-like gestural blooms do not grab me as effectively as the forests.

There are two of each style of work in "Sed Non Satiata", accompanied by a small cameo of a painting which, while largely conforming to the riverscape format, also has a more open, painterly nature. This piece, only a fraction of the size of the artist’s other river scenes, uses similar strong brush-strokes, creating as much an atmosphere as a recognisable landscape, and is all the better for it.

(Fe29 Gallery)

Bronwynne Cornish is a leading New Zealand ceramicist. During her lengthy career, she has worked largely in the medium of earthenware clay, a substance which produce strong, gritty pieces, and which in the right hands can become attractive, caricature-like sculptural forms.

Cornish has used this to its full advantage in creating works that have either been glazed to a polished finish or, in many cases, simply painted. This latter method of working has produced sculptures that stand out as much for their distinctive finish as for their often humorous subject matter.

Fe29’s current exhibition of recent Cornish work focuses largely, as the title suggests, on a series of witty owl-shaped jugs, each imbued with its own strong character. A series of mixed media wind chime-like Dizzy Dancing Birds is also on display, as is a collection of striking ceramic rings.

The stars of the show, however, are three larger-than-life anthropomorphic chickens: Miranda (with Log), May (with Nest), and Stevie, who between them dominate Fe29’s main gallery. Cornish has somehow managed to capture both sides of the chimeric personalities of these bird-women with a ceramicist’s skill and with a delicious wry humour.

By James Dignan

![Rozana Lee, "Drawn to see(a)" [Installation view]. Photo: Beth Garey](https://www.odt.co.nz/sites/default/files/styles/odt_landscape_small_related_stories/public/story/2024/10/blue_oyster_r_lee.jpg?itok=IGhlKMSl)

![Phaeacia (2024), by Paul McLachlan [detail]. Acrylic and rust on canvas.](https://www.odt.co.nz/sites/default/files/styles/odt_landscape_small_related_stories/public/story/2024/09/paul_mclachlan_phaeacia_de.jpg?itok=UuQsvnQc)