![Phaeacia (2024), by Paul McLachlan [detail]. Acrylic and rust on canvas.](https://www.odt.co.nz/sites/default/files/story/2024/09/paul_mclachlan_phaeacia_de.jpg)

(Eastern Southland Gallery)

"Te Au Nui", meaning "big swirling waters" in te reo Māori, is an exhibition that alights upon the Mataura Falls as a site to explore intersections of nature, history, culture and preservation. Paul McLachlan’s unique painting/printmaking approach to image-making is layered, multi-faceted and incredibly detailed, while the material and visual qualities of the works are conceptually and thematically cohesive.

The artist has a studio with an outlook over Te Au Nui (Mataura Falls) and the imagery in the works combine the landscape and its industrial structures with a fluid and intricate approach to abstraction. There are water-like or light-infused flowing motifs and intersecting zip lines. Underpaintings imbue the images with natural tonalities, and their surfaces appear to shimmer in rust oranges or metallic silver.

In one of the works, Phaeacia (2024), the traditional collection of kanakana (lamprey) is implied in a people populated foreground, against a backdrop of underlying industrial structures built at Mataura in the 19th century. The mechanical and organic interstices of line help deliver the idea that history and place are interconnected. This visual quality also supports a conceptual idea expressed in the show: of both human interference and the presence of place, as the artist witnesses it.

(The Dunedin Museum of Natural Mystery)

The Dunedin Museum of Natural Mystery, run by artist and curator Bruce Mahalski, is replete with specimens of natural history, folklore, and ethnological, scientific and local art, including Mahalski’s own sculptural practice.

The process of discovery and wonder at the sheer range and peculiarity of the many exhibits is a compelling feature of the viewing experience. With no space here to be comprehensive, I thought I’d name a handful of oceanic highlights from my visit:

One of the first pieces that caught my eye was the tiny head of a viperfish, with its long needle-like teeth and jutting jaw; it appeared illuminated behind the thick lens of a magnifying glass. The incredibly spiky exoskeleton of a spiny crab was next, a species of king crab found in the waters near Tokyo. A richly iridescent black and white photograph of a magnified whale louse, found on a Hector’s dolphin in the 1990s, caught my eye, as did the subtle blue-grey and orange-brown stripes of approximately 35 species of local molluscs. Installed above this framed collection of limpets, and characteristically juxtaposing scientific fact with speculative wonderment, was an etching of The Daedalus Sea Serpent (1848), depicting a sea monster reputed to have been sighted in the South Atlantic Ocean.

(A Rear Window Project, Dunedin Public Art Gallery)

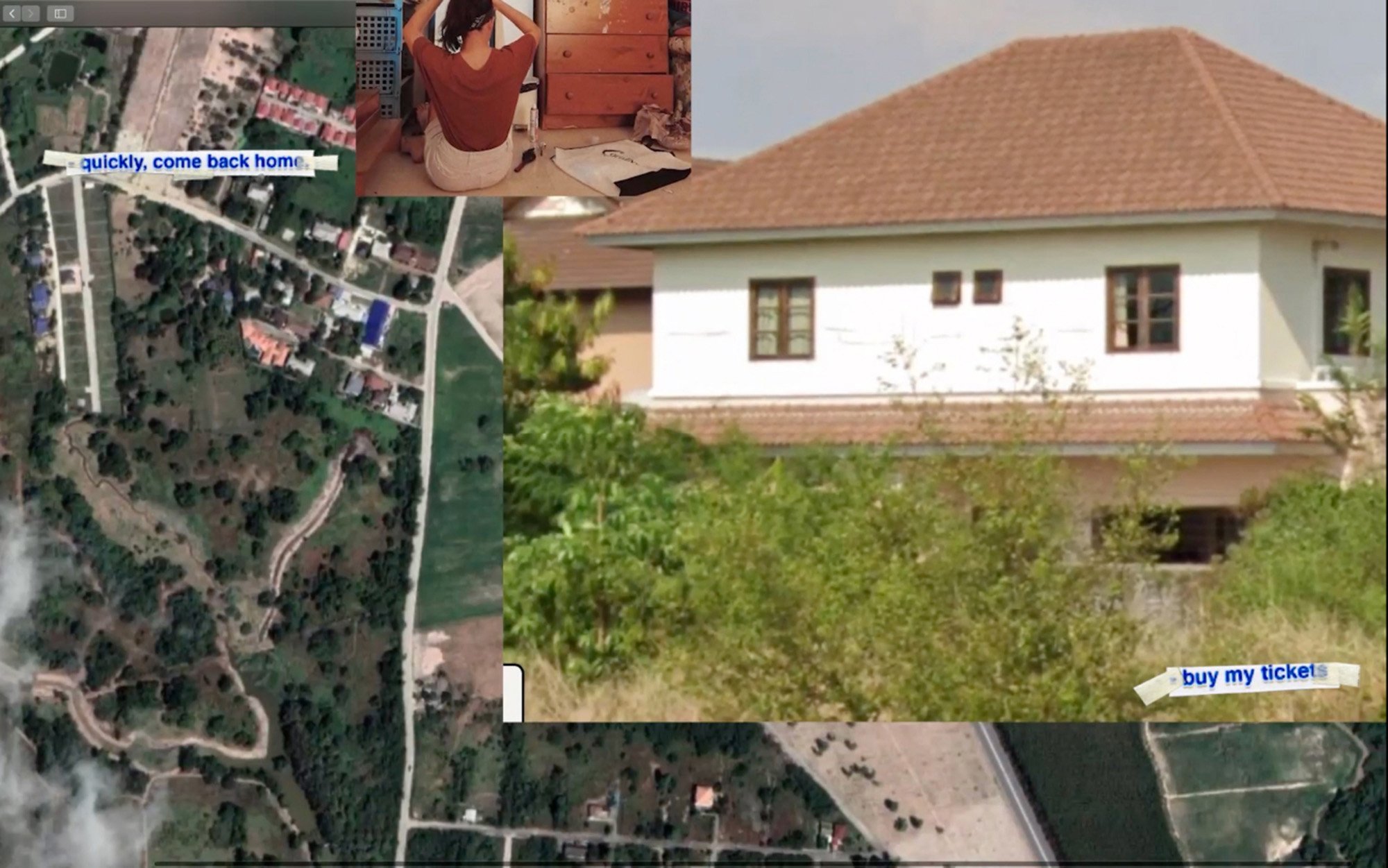

I think I’m homesick is a reflective and narrative-based video work that combines Google Maps imagery, photographic stills and digital collage of Ban Chang in Yatong, the artist’s home town in Thailand.

The street views and maps of Ban Chang appear to jog the artist’s memories of places or stories that involve travel between places. Roads seem to be conduits for memories and re-tellings are connected to place. At one moment, we see the little yellow figure of the Google pegman being dropped into the map, which then opens up a street view, a shared moment, a connection to family and friends.

These places include the artist’s family home; the view of a 7/11 with tidy yet chaotic bundle of powerlines; the location for good Hainanese chicken; and the quiet daytime courtyard where night-time food vendors are located, sometimes visited on the artist’s way home after a night out.

An important bilingual component of the work creates a rhythmic and reflective quality. As the video work plays on repeat, the narrative is recounted both in Thai and English, with relevant subtitles to support each version. I think I’m homesick is low-key yet poignant, and there is a feeling of distance or remoteness in this work as Warisara Thomson speaks through one mediated location to another.

By Joanna Osborne