(The Artist’s Room)

Tessa Barringer’s "A Balancing Act" at The Artist’s Room is a celebration of our native birdlife.

Our native species are at risk from the disturbing and violent changes in our ecosystems. They are at a point of balance — one step from safety, one step from extinction. Barringer captures texture and colour masterfully in her pencil pastel works, and also perfectly captures both the characters and interplay between the birds — hesitant of the human-made objects they are alongside, yet also involved in their own busy, inquisitive lives.

We are part of the dynamic system of checks and balances that make up the natural world, and we are not alone. All other species on the planet share this system, and birds, the last vestiges of the dinosaurs, have come through disaster once before. We can therefore look to them as bellwethers for the vulnerability of the natural world, but with a certain amount of home that maybe — just maybe — disaster is survivable.

In Barringer’s not-so-still lifes, we see the moment of contact between the human and avian world; our creativity is on display in fragile glass and porcelainware. The inference is that our world is no more sturdy than that of our wildlife companions. Send not to ask for whom the bell tolls.

(Brett McDowell Gallery)

Mark Braunias presents an exhibition of two halves with cool organic monochromes and vibrant colours at Brett McDowell Gallery.

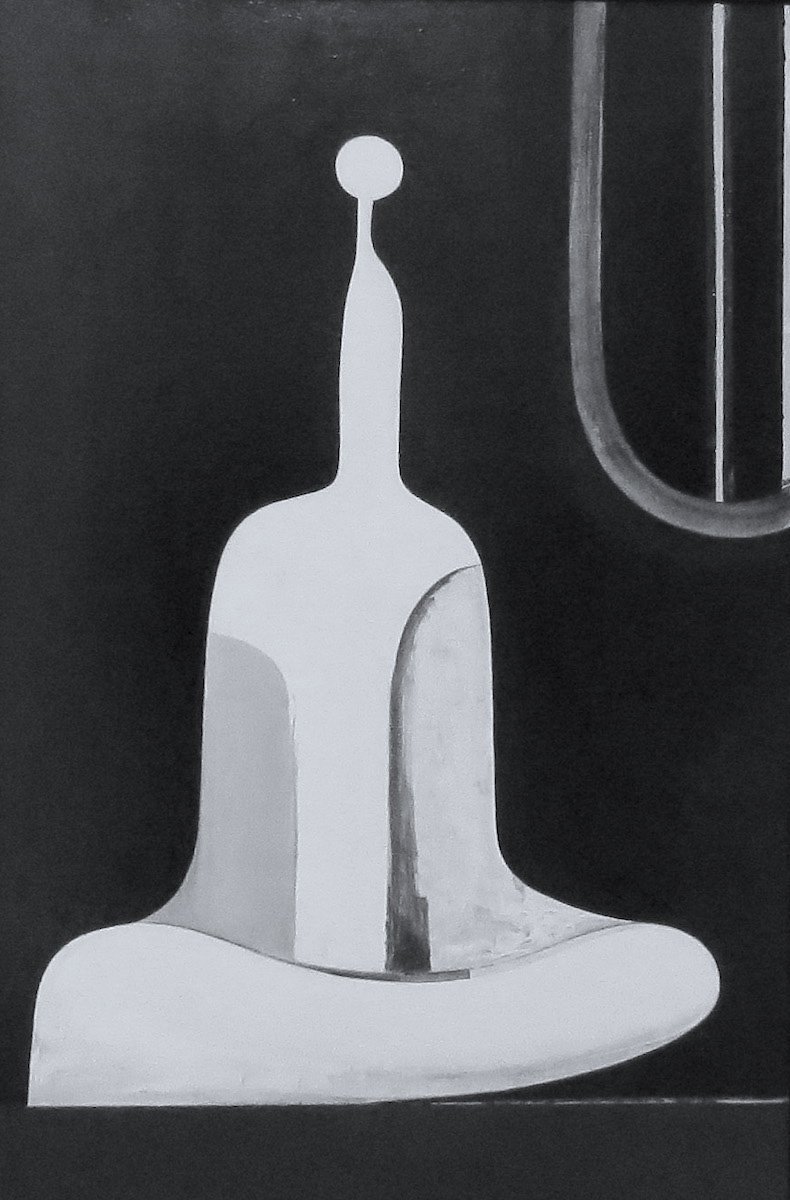

Both series of acrylics occupy a netherworld between surrealism, abstraction, and expressionism. Taking influence from everyone from Picabia and Dalí to McCahon, the works are unsettling and haunting.

The monochromes have an almost sculptural presence, their amorphous alabaster forms floating dislocated against a sea of darkness. Pieces like the almost calligraphic Los tropos and in the distinct nod to McCahon of Lady Waterfalls have an unnerving calm.

Opposite these works are a series of paintings which have a strongly contrasting emotional effect. The vividly coloured face-analogues of Pollyanna is Glad and Twiggy Ginger silently shriek from the walls, the interleaved Sloogan Pamp works punctuating these works with their filmstrip-like triple images, almost suggesting series of inscrutable events leading up to or from the larger images.

There is an almost linear transition between the two series. The austerity of the monochromes leads into the Loco Dreams pieces, in which muted colour is added. A further work, Touche, begins to introduce more figurative forms while adding in further colour. This bridges the gap — though it is still a large leap — to the coloured pieces, and represents a satisfying compromise between the two series.

(Olga)

There are also two distinct series in Kathryn Madill’s exhibition at Olga, despite this being a relatively small exhibition. The exhibition’s title, "Bookkeepers and the Blue Mine" reflect these two series.

Madill’s paintings create a dream landscape inhabited by emotion and memory. Stormy skies sit above an infinite Limbo. There is a sense that time has stopped, and that any events which may occur will be expunged from history, leaving only the haunted memories of those involved.

The Blue Mine works, and an accompanying untitled piece, give evidence that this world is not as it might appear on the surface. Half lake, half rift in the universe, an ultramarine hole sits at the centre of these images, watched by enigmatic figures, one of them starkly, phantasmically white. In one disturbing work, the painter Edvard Munch walks with his dead sister near the edge of the mine, suggesting the idea (which recurs in Madill’s work) that there is a journey and a continuum between life and death on display.

If anything, the Bookkeeper works feel even more personal than the Blue Mine pieces. Generations of figures walk the same non-land, clutching books tightly to their chests as if they are the only traces of memory or property that they retain, guarded as they are passed down through the years.

By James Dignan