(RDS Gallery)

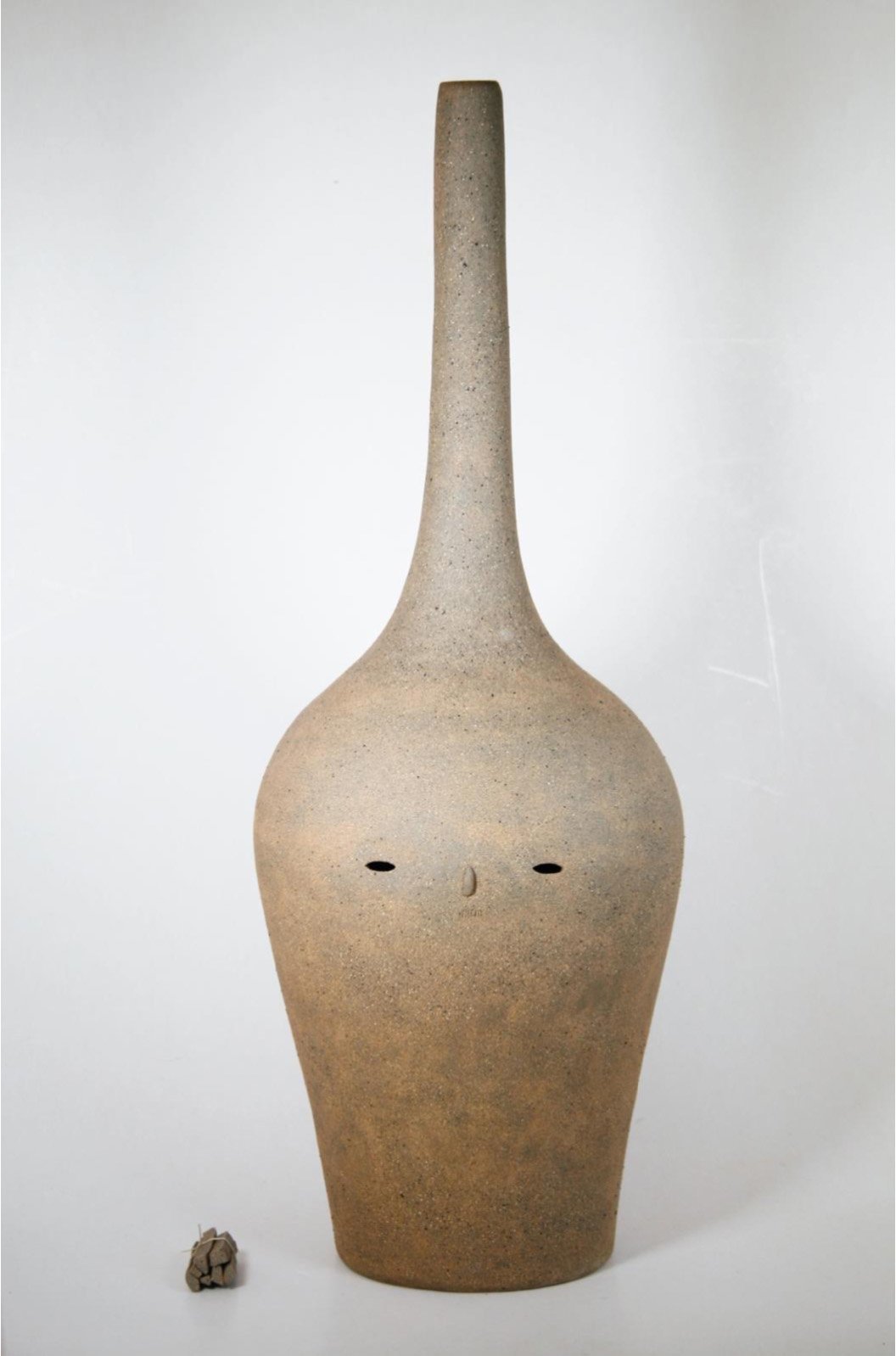

With their presence and countenance, the eighteen slender ceramic vases and one sculptural work that comprise Kate Fitzharris’s exhibition exude companion peace in equal measure to "Companion Piece" — the title of the local artist’s exhibition. If all the works have eyes, most are without a mouth, or if there is one, it is etched lightly into the clay rather than a void like the eyes. The vases that do have incised mouths are small and appear "stitched" like those of a mummy or a Basquiat painting. Yet rather than expressing forced silence, horror, or a withheld scream, the absent or stitched mouths do not detract from an overall sense of peace. If anything, they are enigmatically reticent or independently content. These affective states would therefore seem appropriate if the vases are the type of companion pieces that could accompany one into the afterlife, as the many vessels and vases found in archaeological sites attest. These vessels contained provisions as the deceased made their way through realms of non-being and being (albeit in a different form). This dual framing of the works as companion peace and companion pieces characterises Fitzharris’s exhibition.

In their peaceful state, each piece nevertheless has a distinct personality. Tall Grey (2022) is slender and sombre with almond eyes, no mouth, and small arms clasping itself; Big Long Neck (2022) with small eyes and a stitched mouth is non-plussed and, as if iterating the notion of companionability, has a small bundle of wood. Go well into the next stage, they suggest.

(Wave Project Space)

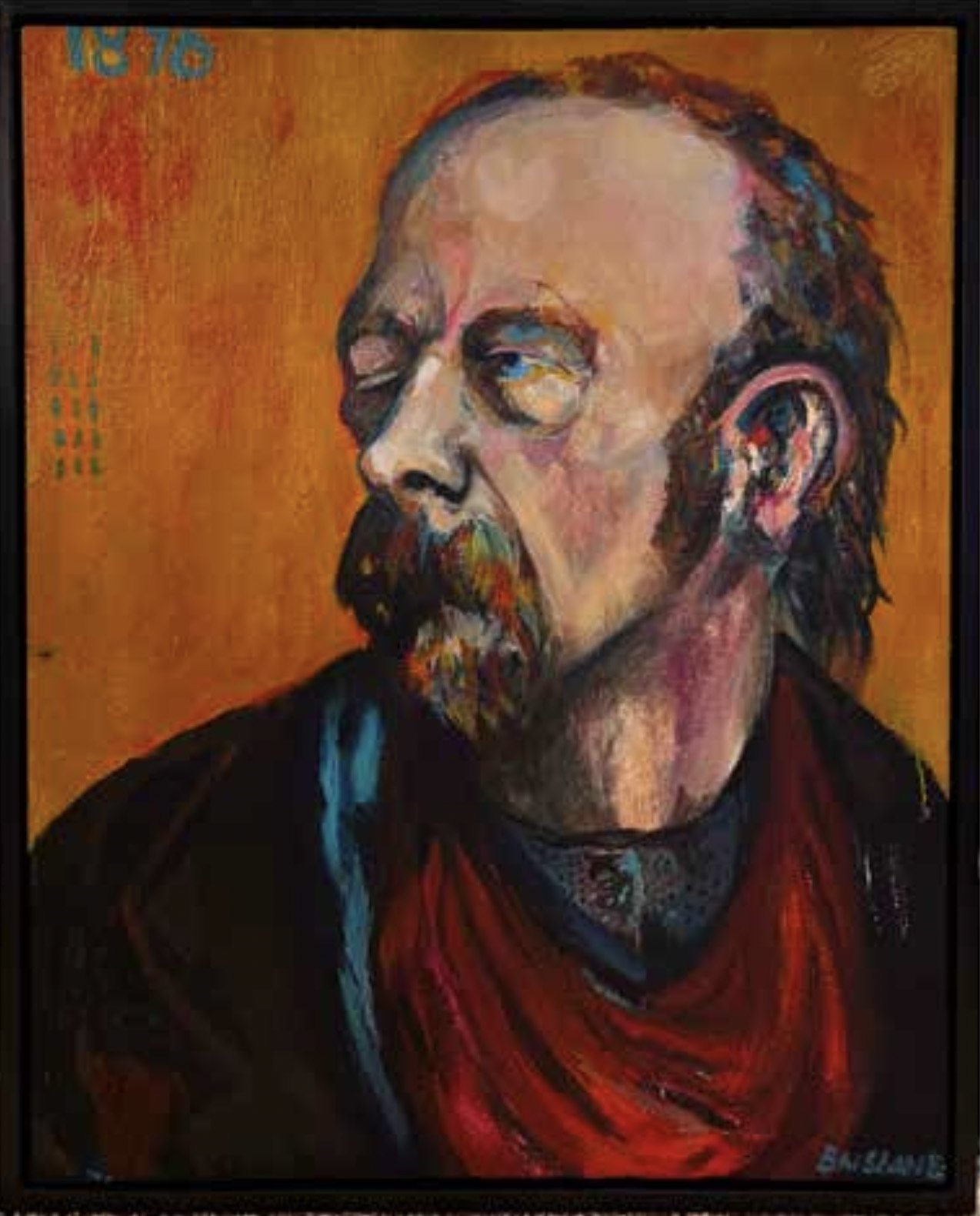

"New Dunedin Painting (redux)" is a group exhibition of memorial to an earlier group exhibition titled "New Dunedin Painting" — organised by Flynn Morris-Clarke and Anya Sinclair at the Brick Brothers Gallery in 2013 — to Morris-Clarke and to Danny Brisbane: two young artists who passed away (in separate circumstances) in 2020. As with the first exhibition, this "reimagining" celebrates the eclecticism of painting in Otepoti Dunedin. Fittingly, the current exhibition includes paintings by artists in the first exhibition and by new artists, including the work of Morris-Clarke and Brisbane. Curated by Kari Schmidt and Michael Greaves, the exhibition also centres the Dunedin School of Art (DSA) as an organising principle, with most artists having studied (or taught) at the DSA.

Given the organisational variables of tribute, memorial, and association, the curators opted for a salon-style hang in which works are installed in close proximity and irregular arrangement to accentuate new visual and psychological connections. This enables the subject of Danny Brisbane’s painting, Cole Younger 1876 (2011) to gaze askance at the majority of the works installed on the main wall and to be met by the stares of two collaged faces (by Sylvie Kaos). A purple owl with piercing yellow eyes by Pete Wheeler is positioned above a large landscape by James Bellaney as if flying over the terrain. Beneath, two landscape works featuring a pathway through a forest (by Philip Madill and Sam Foley) echo each other, while a young woman (by Pippi Miller) looks over and towards flowers of mourning (by Anya Sinclair).

(DPAG Rear Window)

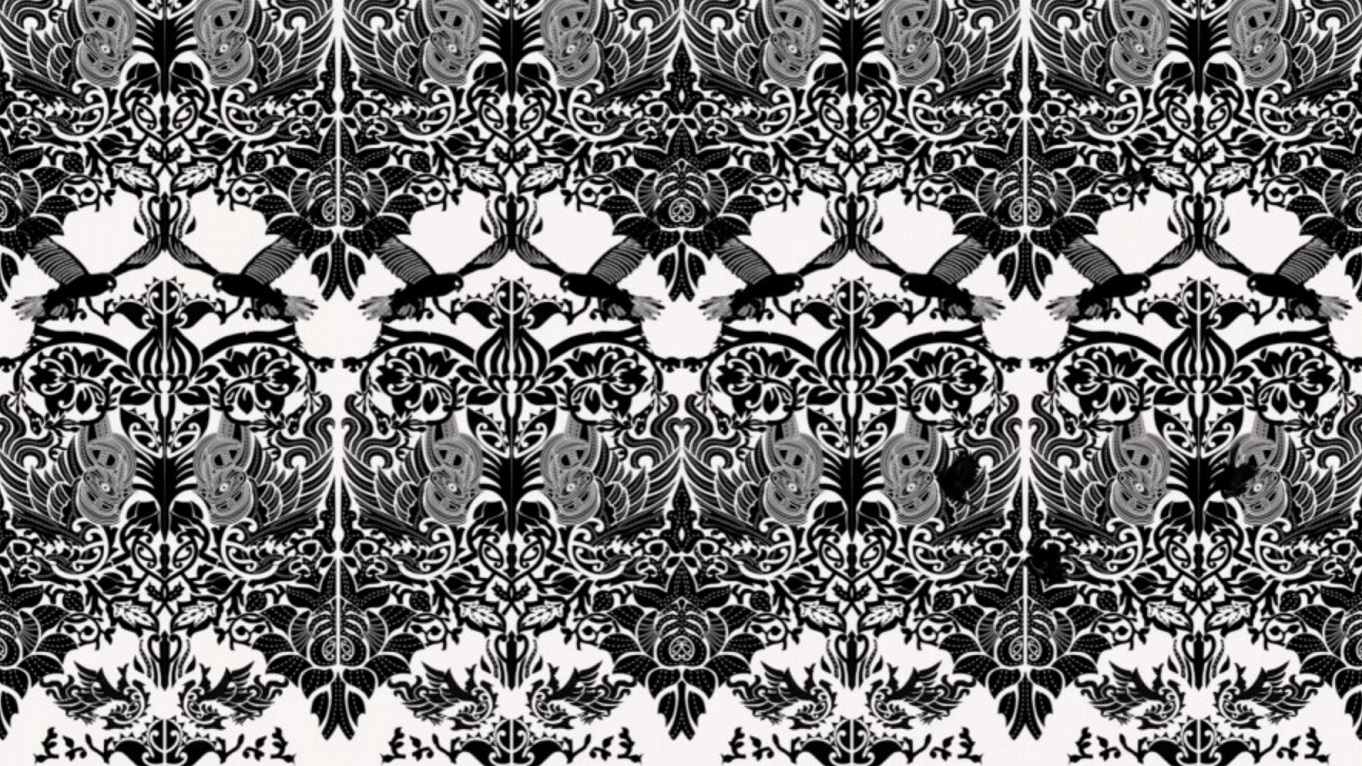

In a visually complex, kaleidoscopic, black and white animation by artist and designer Cecelia Kumeora (Te Ati Haunui-a-Paparangi), karearea (New Zealand falcon), the serpentine-like manaia figure in Maori cosmology and design, and niho taniwha (chevron pattern) alternately supplant bands of peacocks in a William Morris wallpaper pattern. The decolonial invasion of the Victorian Arts and Crafts movement initiated by Morris — here a cipher of British imperialism — begins with a circular fly-in of karearea who position themselves over the peacocks and flap their wings. This action in turn generates peacocks with stylistic features found in Maori whakairo (carving), such as heavy outlines and flattened forms. At a speed difficult to track accurately, a photo-realistic manaia is dropped into another band of patterning beneath, followed by two horizontal swirls of small niho taniwha swarming rhythmically in place of the supplanted peacock. The invasion of karearea, manaia, and niho taniwha morph, intervene, and disrupt British flora and fauna, the traditional subject matter of the Victorian-era Arts and Crafts movement which flourished at the peak of British colonialism.

In choosing an endemic bird with a variable status of "vulnerable" and "recovering," a bird which can travel faster than 100kmh and catch prey larger than itself, Kumeora has selected a highly significant subject to visualise decolonisation. The invasion, the recovery of karearea exemplifies an instance of kaitiakitanga (guardianship) in which the presence and well-being of the bird is necessarily connected to the healing of whenua (land) and taiao (nature): kaitiakitanga as an integral trajectory of decolonisation.

![Rozana Lee, "Drawn to see(a)" [Installation view]. Photo: Beth Garey](https://www.odt.co.nz/sites/default/files/styles/odt_landscape_small_related_stories/public/story/2024/10/blue_oyster_r_lee.jpg?itok=IGhlKMSl)

![Phaeacia (2024), by Paul McLachlan [detail]. Acrylic and rust on canvas.](https://www.odt.co.nz/sites/default/files/styles/odt_landscape_small_related_stories/public/story/2024/09/paul_mclachlan_phaeacia_de.jpg?itok=UuQsvnQc)