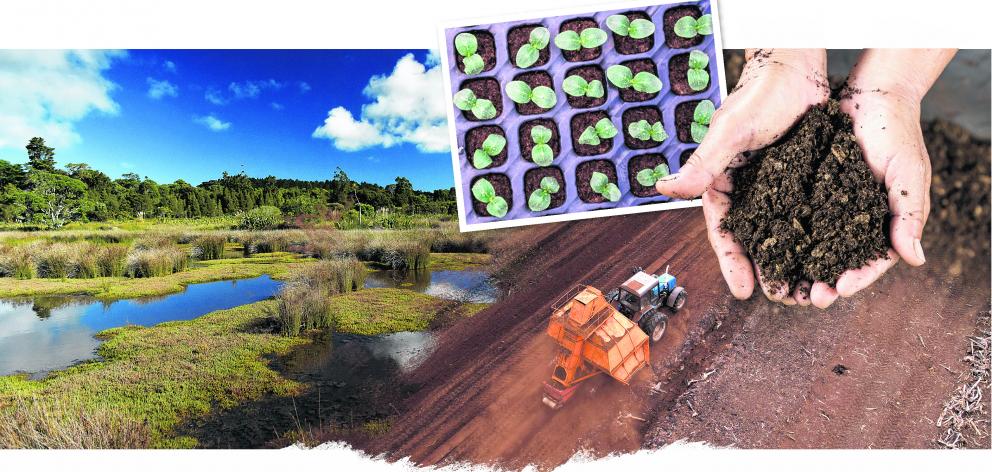

A row of recycled egg cartons - free range, of course - is lined up on the window end of the dining room table to catch the light.

The cardboard cartons’ cells are filled with a light brown, fibrous soil - peat - an ideal seed germinating media that is naturally sterile and has an enormous capacity to hold life-giving water.

Emerging from the peat are dozens of slender shoots and tender, light green leaves; seeds brought to life by moisture and warmth; seedlings that will be transplanted to the backyard garden to produce this year’s bountiful crop of peas, tomatoes, lettuce, carrots, beans, spring onions, spinach...

No chemically ripened, air miles-heavy, pesticide-laden produce here; just home-grown, money-saving, nutritious, delicious, goodness.

Or maybe not.

Little does this enthusiastic gardener know - nor most of the myriad other busy springtime green thumbs - that they are possibly damaging the planet with each seed they sprout.

Peat. Boggy, swampy ground that is not much good for anything except to be drained for farming, burnt for heating, added to potting mix for azaleas and blueberries or dried and then rehydrated to germinate seeds. That is what we used to think.

Peat is in fact a fascinating material and peatlands are an ecological and climatological marvel.

Peatlands provide unique and valuable ecosystems. They regulate water flows, preventing seawater intrusion as well as helping minimise the risk of flooding and drought. They are home to a rich variety of plants and animals found nowhere else.

In most environments, when something dies, it decays and its constituent parts are recycled.

But peat is different. Peat is the partially decomposed remains of ancient plants that have accumulated in waterlogged places high in acidity but deficient in oxygen and nutrients. These conditions prevent the material from fully decomposing. Over millennia, this material builds up and becomes several metres thick.

Because the plants that form peat do not fully decompose they do not release all the carbon they accumulated while living. This makes them an important carbon sink.

Peatlands cover an estimated 3% of the surface of the planet, but they punch well above their weight. They contain an estimated 644 gigatonnes to 1073 gigatonnes (Gt) of carbon - almost half of all soil carbon on the planet.

This is what makes the disturbance and destruction of peatlands significant in these crucial opening decades of the anthropocene - the current geological age marked by a dramatic increase in human activity. The central feature of this epoch is man-made climate change, caused by a dangerous build up of greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide (CO2), in the atmosphere.

To date, much of the concern about greenhouse gas emissions has been focused on burning fossil fuels for electricity, heat and transportation, as well as, particularly in agriculture-dependent countries such as New Zealand, on emissions from farming.

Now peat is coming into the frame.

Worldwide, about 15% of the world’s peatlands have been drained. This has released huge quantities of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, estimated at between 421Gt and 701Gt of CO2. To put that in context, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says the world cannot afford to put more than 300Gt to 500Gt of CO2 into the atmosphere during the coming eight years if we want a 50% to 83% chance of keeping global warming below 1.5deg C - the target for avoiding a catastrophic climate change tipping point.

New Zealand is part of the peat story. Much of lowland, pre-colonial New Zealand was covered in extensive wetlands that included about 230,000ha of peatlands. During the past 150 years most of those peatlands, about 178,000ha, were drained and converted to pasture, plus a bit of forestry.

Waikato has about half of Aotearoa’s peatlands, of which only 20,000ha are in their original state. Southland is the country’s other wetlands stronghold. Estimates of its peatlands vary wildly, but most calculations of how much remains untouched sit between 2% and 10% of the original total. They include the Bayswater Scenic Reserve, near Otautau, a 424ha peat bog, purchased by the Government in two stages, in 1993 and 2007.

"They are incredibly valuable in terms of their biodiversity," the University of Waikato ecosystem researcher says.

"There are unique plant and animal communities that live there and nowhere else.

"But the global significance of peatlands is their ability to store carbon for thousands of years - which is very different from forests ... which only take up carbon for a few decades."

Prof Campbell has been looking at how much New Zealand’s drained peatlands are contributing to the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. It is quite considerable.

New Zealand uses an outdated way of calculating those emissions, Prof Campbell says. Using the latest IPCC methodology, he estimates drained peatlands could be responsible for the equivalent to 5% to 7% of the country’s gross greenhouse gas emissions, or 8% to 10% of its net emissions.

"That’s huge ... The role of peatlands has almost been swept under the carpet until recently."

That, to date, is as far as the story has gone.

It has ignored the fact that New Zealand’s drained peatlands are not only being used as pasture. Kiwi peat is also excavated, dried, processed, packaged and then sold to wholesale plant producers and home gardeners to germinate seeds for this year’s veges, flowers, shrubs and trees.

It is not a big industry in this country. There are only two peat producers, one in Waikato and one in Southland. Combined, they produce about 50,000cu m of peat a year, Matthew Dolan, chief executive of New Zealand Plant Producers Inc (NZPPI), says.

But excavating that peat and, so, releasing the stored carbon does create greenhouse gases. In fact, an estimated 6400 tonnes of CO2 per year. This is believed to be the first time the greenhouse gas emissions of New Zealand peat excavation have been calculated and publicised.

It could be considered insignificant against some of our bigger emission sources. But as the clock ticks down on an ever more apparent climate emergency and the latest data reveals that New Zealand’s annual greenhouse gas emissions, rather than dropping, are 26% higher than in 1990, every bit counts.

The annual CO2 emissions from New Zealand peat excavation are equivalent to 3500 petrol cars being driven for one year.

To offset those CO2 emissions would require planting 109,150 native New Zealand trees and letting them grow for 20 years. And repeating that every year.

What, then, to do about peat?

Worldwide, increasing attention is being paid to this partially decomposed vegetable matter. When it comes to looking for nature-based solutions to climate change, some scientists have suggested that restoring peatlands could be a much better global solution than planting trees.

On average, each hectare of peatland holds 1375 tonnes of soil carbon - 10 times more than normal mineral soil. Combined, peatlands contain twice as much carbon as all the forests of the world.

Humans have been draining peatlands for agriculture and burning it for fuel for more than a thousand years.

Finland, for example, has 60 power plants that burn peat, providing about 6% of the country’s energy needs.

Canada produces about 1.3 million tonnes of horticultural peat moss each year, making it the world’s largest exporter.

Today, half the world’s peatland emissions come from Southeast Asian nations where high rates of deforestation, and drainage are decomposing the peat.

But the tide is turning.

In 2016, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which has 14,000 members including New Zealand’s Department of Conservation, held a world congress. Motions passed included a call for countries to place a moratorium on peat exploitation and to commit to peatland preservation.

The next year, a report by the United Nations Environment Programme concluded, "The overriding solution to ensuring the conservation of peatlands is relatively simple: keep them wet. Or, if they have been drained, re-wet them".

Steps, sometimes faltering, are being taken.

Russia and Germany have a joint project to re-wet 70,000ha of drained peatlands in Russia. It is urgently needed. Last year, Siberian peatland fires emitted a record 244 million tonnes of CO2.

Indonesia set an ambitious four-year goal of restoring 2.6 million hectares of peatland by 2020. Last year, it gave itself an extension, having achieved 45% of that goal.

The Scottish government is leading a $100 million-plus restoration of 250,000ha the country’s peat bogs by 2030. It is one of Scotland’s key strategies to help it become a net-zero greenhouse gas emitter by 2045.

The United Kingdom is banning the sale of peat compost to gardeners by 2024 and is restoring 35,000ha of peatland by 2025.

Three peatland-rich states in Germany are re-wetting their moorlands and selling carbon offset certificates.

On the back of all this, an emerging, although actually re-emerging, practice is paludiculture - crop production on peatlands in a way that maintains the peat and its ecosystem.

Here in New Zealand, the peat conversation is only just getting going.

One of the phrases that will become more prominent is "nature-based solutions". It comes from the daunting idea that rapidly cutting fossil fuel emissions will not, on its own, do the job in time and that we lack the technologies, and the time to develop them, before the tipping point is in the rearview mirror. An urgent task, therefore, on top of cutting emissions, is to enable "nature-based solutions" - giving nature all the rope it needs to do its job of absorbing carbon.

The key contenders are growing trees, changing agricultural practices, restoring marine ecosystems and ... restoring peatlands.

New Zealand’s Minister for Climate Change, James Shaw, mentioned nature-based solutions in a speech he gave, in July.

Titled "It falls to us", the speech about the Government’s yet-to-be-unveiled Emissions Reduction Plan, listed five principles that Shaw said would be central to the country’s climate response.

Principle three, he said, would be "to enhance the role nature-based solutions can play in helping tackle the climate crisis".

"If we can do this, we can have a truly holistic approach to stopping the loss and degradation of carbon- and species-rich ecosystems on land and in the ocean - especially areas like forests, wetlands, and coastal ecosystems."

In 2019, the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, Simon Upton, wrote a comprehensive report outlining his researched recommendations for how New Zealand should tackle climate change and what it could mean for our landscapes.

Peat got a mention. Rewetting was discussed.

"An estimated 146,000 hectares of organic or peat soils are currently under pasture," Upton wrote.

"Even now, 100 to 150 years since the drainage of these wetlands began, an estimated 0.5 to 2 megatonnes of carbon dioxide is released annually across New Zealand as a result of the continued decomposition of these carbon pools.

"Re-flooding some of these landscapes and restoring the wetlands could halt these losses and, in the long term, potentially return far more carbon to the soils than forests could ever hold."

This week, in response to questions from The Weekend Mix, the office of the Climate Change Commission seemed to diplomatically suggest the Government needed to move beyond talk.

Peat, the Commission says, needs to be in the equation.

Asked what should be done about greenhouse gas emissions from drained peatlands, Commission principal analyst Phil Wiles said the Government needed a better handle on the loss of carbon from peatlands and must factor that into emissions targets.

"The commission has recommended the Government develop methods to account for carbon losses from peatlands in its emissions budgets and that it takes steps to prevent these losses," Wiles says.

It is important that all sources of emissions, including from peat excavation, are taken into account.

"Rewetting peat soils can halt and reverse carbon losses, and would have co-benefits for climate adaptation, water quality, biodiversity, and managing extreme rainfall.

"The Government would need to consider which policy options would be most appropriately implemented to address this problem."

The Minister acknowledged the advice he had received from the commission on peatlands. The next step, it appears, is more talk.

"The Government will soon begin inviting ideas and feedback on what could go into the final Emissions Reduction Plan, and we’d certainly welcome people’s views on the role of New Zealand’s peatlands,” Shaw told The Weekend Mix.

In response to an emailed question about what nature-based solutions would look like in practice, The Weekend Mix was requested to ask again closer to the time the Emissions Reduction Plan consultation was released.

Last week, the plan’s release date was pushed back five months, to May, 2022. The consultation document will be out next month.

The Government might be tardy, but responsibility also rests with each of us, from the Beehive to the back yard garden plot.

The head of NZPPI says the benefits of peat in plant production are significant.

"In the New Zealand industry, at its current scale, it’s probably a net benefit to be honest," Dolan says.

Prof Campbell has another point of view.

More sustainable alternatives, such as green waste for compost and coconut fibre for germinating seeds, are readily available, he says.

"Think of new compost as equivalent to bio-fuels whereas harvesting peat ... is analogous to harvesting coal."

If you are a gardener about to germinate seed, do think it through - for the love of peat.