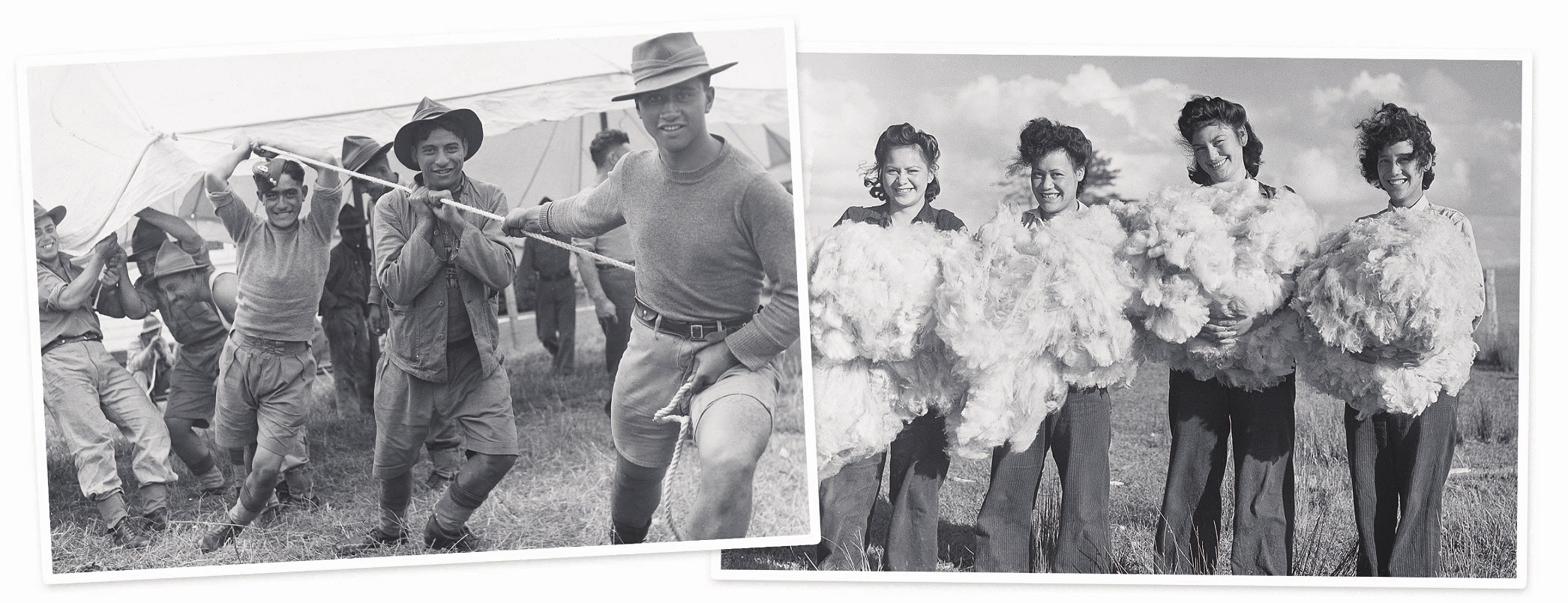

Among the stories that deserve to be much better known from Aotearoa’s World War 2 experience is the story of Te Rau Aroha, the taraka kai of the 28th Māori Battalion.

Māori children in native schools up and down the motu fundraised to buy the truck — and then provision it — to support the men from their whānau, hapū and iwi who were fighting overseas.

The taraka kai (canteen truck) saw service in North Africa, Syria and Italy, during which time it was shot up and blown up to the point of being irreparable. But repaired it was, by the soldiers of the battalion, such was its importance as a connection to home.

One contemporary report says "on several occasions when it seemed beyond repair and had been ordered to the wrecking heap by higher authorities, they took it upon themselves to tow the bus wherever they went".

Then, at the war’s end, when it looked like the truck might be abandoned in Europe, soldiers of the battalion threatened to strike. And the truck was duly brought home, whereupon it was toured back through all the kāinga that had supported it during the war, as an expression of the soldiers’ gratitude. Gratitude for the pennies, shillings and pounds raised by all those school children back home.

The story is one of many in a new two-volume set of books that detail the breadth and depth of the Māori home front during the war, and the motivations behind that support.

The generously illustrated books, Raupanga, which is in te reo Māori, and Te Hau Kāinga, in English, tell overlapping stories of those efforts, sometimes covering the same ground, sometimes diverging somewhat in their focus.

While there is a long list of contributors across the two books, the common ingredient is the work of University of Otago Ōtākou Whakaihu Waka historians Prof Angela Wanhalla and Emeritus Prof Lachy Paterson, the latter of whom also did the translations for Raupanga — deliberately pitching the level of te reo to make it accessible to high school students.

"There hasn’t been a huge amount of history on the home front, but what there has been tended to not really look at the Māori side at all. Not in much depth."

And there’s a lot there. Prof Wanhalla rattles off a few statistics that give a taste of it.

The organisation that co-ordinated the work of tāngata whenua, the Māori War Effort Organisation, had helped set up 398 tribal committees across the country by 1945. There were 51 executive committees.

"It was all volunteer effort. That demonstrates the weight and significance of what this meant for Māori communities."

This at a time when the Māori population was still less than 100,000.

"I think the thing that struck us quite a lot in this project was not just the widespread scale of the effort, but the fact that the Māori population is only maybe — at the start of the war — about 93,000-94,000," Prof Wanhalla says.

In 1945, most of them were still under the age of 20.

"So the adult population only makes up 43% and they’re all working in some shape or form towards the war effort."

That included work directly related to the fighting, for the Colonial Ammunition Company for example, and the home guard, through to shearing, food production — and collecting seaweed.

Just how thinly spread they were soon became apparent.

"As the war went on, so many Māori men were enlisting that they didn’t have enough shearers," Prof Paterson points out.

Some had to be hauled back out of uniform and back to the woolshed.

"A lot of the men were not happy. They were wanting to go overseas, but it was actually more important for the country as a whole that you had shearers working."

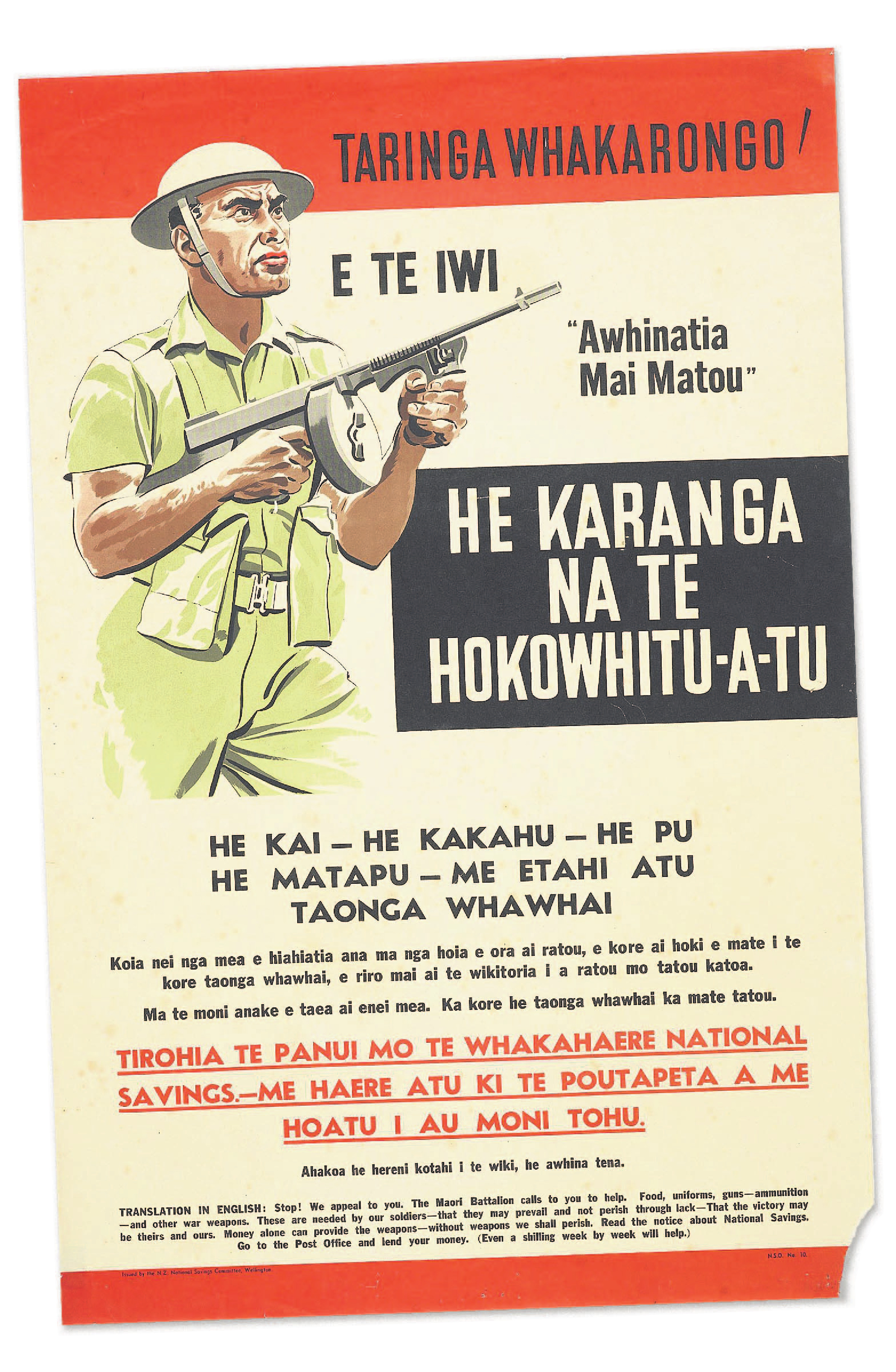

The work of the Māori War Effort Organisation (MWEO) looms large across the two books, both for its extraordinary wartime achievements co-ordinating the Māori mobilisation but also for what it represented for Māori.

This is intimately connected to the famous exhortation of Sir Āpriana Ngata for Māori to fight in the war, as "the price of citizenship" as he put it.

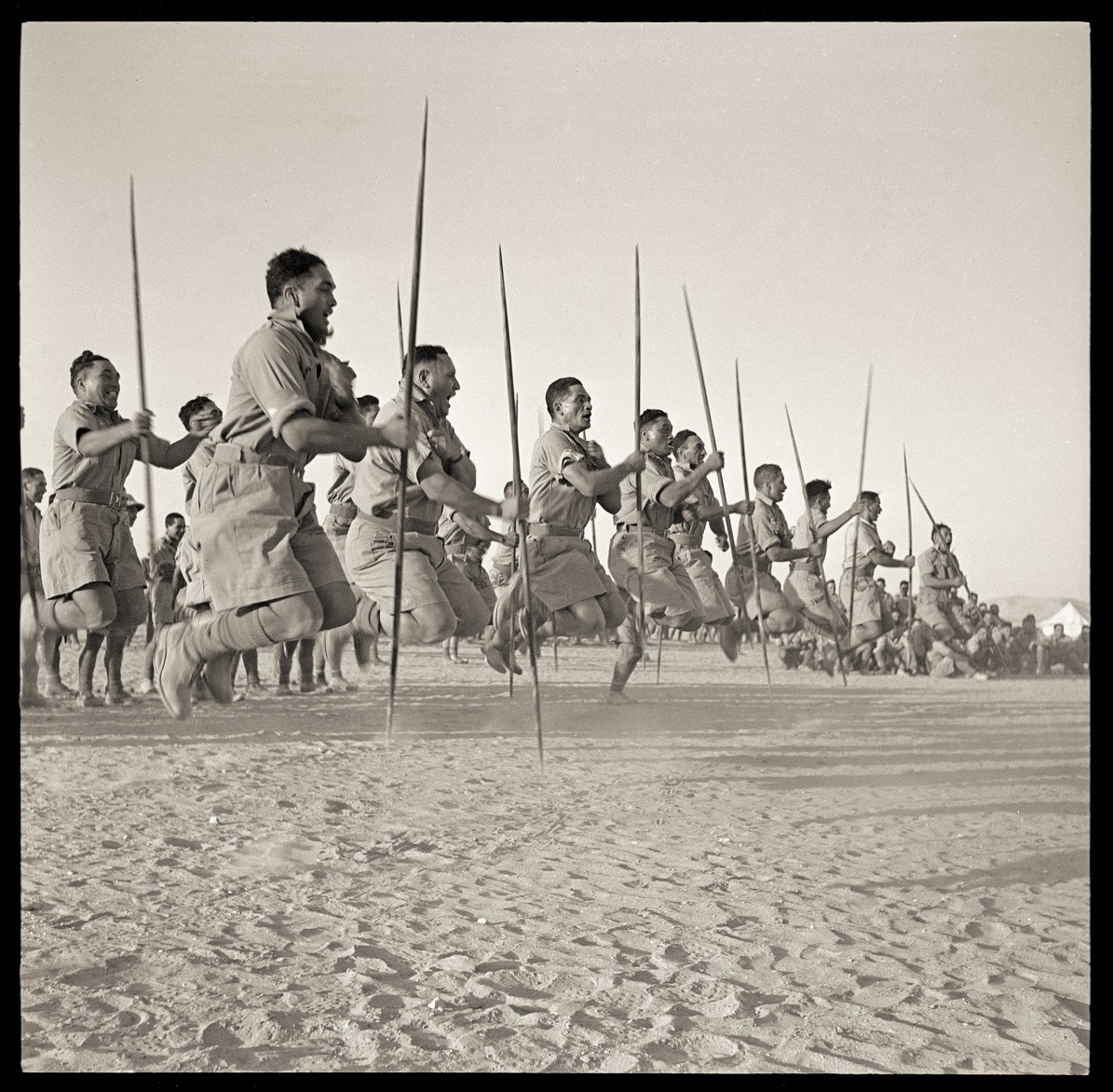

The hope was that Māori efforts on the battlefield would translate into an improvement in the status of Māori after the war. For that reason, Ngata and other Māori MPs had pushed for the formation of a separate Māori battalion with its own Māori officers, so there could be no question about their contribution.

"Pākehā wouldn't be able to say, well, what did you do?" Prof Paterson says.

Similarly, the MWEO helped organise the Māori home front effort in a way that would be undeniable when the peace came, so that the peace dividend might this time be extended to Māori.

"Māori are stepping up to embody a treaty relationship. While the MWEO is the other arm of that treaty relationship."

That was more about Article 2, Prof Paterson says.

"About Māori actually running their own things."

And doing it effectively.

"The Māori War Effort Organisation, MWEO, was such a big thing during this time," Prof Paterson says.

"And initially it was set up as, ‘oh, maybe Māori can organise some recruitment of Māori soldiers’. But it just grew."

In the event they recruited for overseas and at home, worked with Māori farmers to boost production, became involved in patriotic fundraising, and as the war was coming to an end they also had their own Māori welfare officers.

"And to a large extent, the government allowed this to flourish because it was going in the same direction in terms of being part of the war effort."

Māori saw it as the future, post-war, as an expression of te tino rangatiratanga guaranteed in the Treaty of Waitangi, that could restore the status of Māori in Aotearoa a century on from its signing.

However, the Pākehā-run Native Department was very much against it.

"They were so effective, which is why it was a bit scary for the Native Department," Prof Paterson says.

In the event, the Pākehā-run department won. Soon after the war finished, the government shut the MWEO down, despite a series of national hui in 1944, initiated by Southern Māori MP Eruera Tirikatene, to try to save the organisation.

By doing so, the government "effectively destroyed the incentive and initiative of a large measure of self-determination which had been the motivating factor behind the tribal committees during the time of the Māori War Effort Organisation" Ngātata Love wrote in an earlier history, quoted again in Raupanga.

The complementary motivations Māori brought to their work, both overseas and on the home front, is a recurrent theme of the books.

Food production provides another example.

Growing food met the requirement to feed your own community while contributing to the war effort — but it also protected the land.

"That way it can’t be taken — because some parts of the country will be taken for defence. Raglan's a famous case," Prof Wanhalla says.

"So I think there is a real awareness of that. By growing the food, you’re positioning yourself as being involved in the war effort, but you’re also looking after your own people at the same time and the land.

In the Waiariki district, delegates to a hui in Ōhinemutu decided to set up their own primary production committees and production of maize tripled by the following year — the largest area 1200 acres on Matakana Island.

An assessment by the MWEO found Māori farmers had out-produced their Pāhekā counterparts.

The food met all sorts of needs at various times, Māori farmers were at one stage asked to produce 2000 tonnes of kūmara to feed American soldiers stationed in Aotearoa.

However, despite these efforts, Māori continued to face the extra challenge of a colonial settler society’s institutional racism.

In 1942, Ngati Rereahu wrote to Paraire Paikea, the MP for Te Tai Tokerau and minister with responsibility for the MWEO, offering King Country land to grow wheat.

"Many of our people are working fulltime in the timber industry and these are willing to pool their services during Saturday and Sunday to assist in securing the maximum production," they wrote.

But the offer was knocked back, Pākehā government officials suspicious it was an attempt to get free wheat seed.

It wasn’t the only area in which Māori met obstacles to their war effort contribution, coloured by racism.

Ngata observed that the small number of Māori women admitted to the Royal New Zealand Air Force were relegated to scrubbing the dining halls.

The head nurse at Greytown Hospital refused to train Māori nurses because, given the small size of the hospital, they would have to socialise with Pākehā nurses.

"Please do not think that I dislike Māori, for there are many I admire," she wrote.

Similarly, after Māori women from the north were directed to work in a Wellington munitions factory, an official wrote that "no further Māori girls should be directed" to the work because it was "undesireable that Māoris should be sent forward to this work as they are required to be accommodated in the same premises as European women".

"It’s quite confronting to read that kind of language in the archives," Prof Wanhalla says.

New Zealand society was happy to have labour for its arms factories, but otherwise a colour bar was to be maintained.

"If they’re in hospitals, they can be in the laundry or the kitchen."

Such attitudes lingered after the war, Prof Paterson says. The Māori officers who had acquired a great many administrative skills during the war were largely denied the opportunity to apply them in peacetime.

"Within government, they could really only get work within the Native Department or Māori Affairs.

"The opportunities didn’t necessarily open up for them."

Prominent among these efforts were petitions, backed by Kīngitanga leader Te Puea Hērangi, asking that the government return land at Ōrākei to Ngāti Whātua, in part because of its importance in supporting Māori who had moved to Auckland to work in war-related industries — and who were being turned away from accommodation.

Ōrākei couldn’t be saved at that time, but the struggle would have its sequel later at Bastion Point, Takaparawhau.

Te Puea was also a leading figure in fundraising, particularly with the Red Cross, concerned to ensure that when men came home, that they could be supported by sick and wounded funds.

There was limited trust that the government would meet that responsibility.

Māori endeavour also extended to the bounty of Tangaroa, including collecting agar seaweed when access to the product — essential across a range of uses from food preservation to health science — was disrupted by the war, especially after Japan’s entry.

Much of the best resource was along coastline adjacent to Māori land.

There wasn’t a lot of money in the work of harvesting and drying it, but it played a seasonal role in local economies.

"It was done to supplement what they were doing to keep their farms operating," Prof Wanhalla says.

The professors’ work was supported by a Marsden grant, and Prof Wanhalla now has further Marsden funding to look at how Māori servicemen fared when they returned from the war.

"We don’t understand what rehabilitation looked like, really," Prof Wanhalla says.

"The thing we know the least about is ... Māori had the highest casualty rate of all units in the Second New Zealand Expeditionary Force. But we know nothing about the range of those wounds.

"How many were gunshot wounds, shrapnel impact, whether or not it was disease that was more important. And then how they were treated when they came home. So what was the impact on their health, both physical and psychological?"

What is known, and recorded in Raupanga, is that the driver of Te Rau Aroha, the canteen truck, Charles (Charlie Y.M.) Bennet, made it home alive — as he joined the truck’s tour around the kāinga on its return to Aotearoa.

But many others paid the ultimate price of citizenship.

The two books recount "one of the largest Māori gatherings of modern times", as it was described, when a Victoria Cross was posthumously awarded in 1943 to Second Lieutenant Te Moananui-a-Kiwa Ngārimu, for his bravery in Tunisia.

It was an opportunity for Māori to highlight their achievements in war to a national audience.

But for some the cost was beyond any accounting.

Asked if she was proud of her son’s VC, Moana Ngārimu’s mother responded: "Oh, no. I would much rather have my son."