For its first 50 years, the main building of the Seacliff asylum was the largest in New Zealand. Jonathan Howard charts its rise and fall.

The Seacliff Lunatic Asylum (as it was originally known) was built from 1879-84 to replace the Dunedin Asylum (1862-84), which stood where Otago Boys' High School is today.

R.A. Lawson (1833-1902) designed it, in the Scottish Baronial style, and the main building contractor was James Gore (1834-1917), who had previously built All Saints Church and the Temperance Hall in Dunedin.

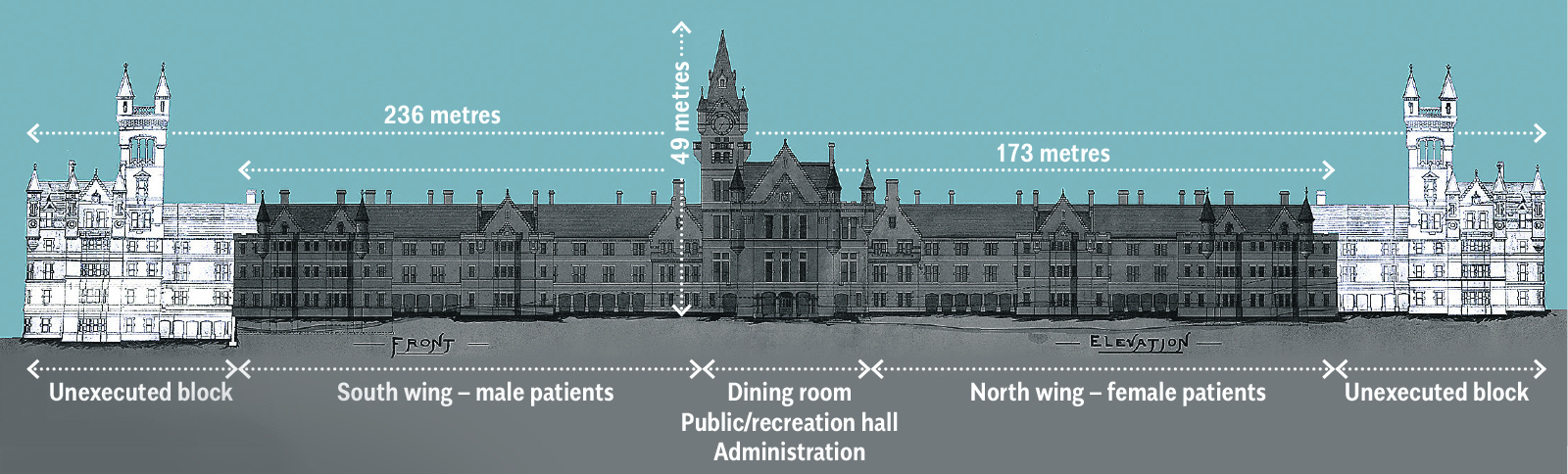

For its first 50 years the main building was the largest in Aotearoa, at 173m long - which was still shorter than the original plan of 228m. Yet the scale and history of this building is dwarfed by the experiences of those who inhabited it, which this article could not do justice.

Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga has recognised the outstanding historic and cultural significance of the wider Seacliff Lunatic Asylum site as a Category 1 on the New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero.

Further information can be found in Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kawanatanga, Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena and the Dunedin Public Libraries Kā Kete Wānaka o Ōtepoti. Many readers will also have family stories of their own.

- Text, photographs and concept by Jonathan Howard

This Burton Bros photograph shows the building c.1890, shortly after Sir Frederic Truby King (1858-1938) was appointed medical superintendent. There were three storeys at the front and two behind as it was built into a slope.

Even before its completion, groundwater flooding and ongoing land movement were identified as damaging the building’s foundations, and in 1885 it was noted that the instability of the site “threatens complete destruction”.

After damage to the north wing and a slip behind it in 1887 a Royal Commission was established to assess the causes.

Issues identified before, during and after the commission included the building design being too long, heavy and high to be built across a slope of varying geology, ineffective drainage, and variable standards in materials (especially bricks and concrete) and in adherence to the design during construction.

Replacement of part of the north wing is already seen in the main photograph and, despite improved drainage, repairs, modifications and partial demolitions, damage spread south over time. . . leading inexorably to evacuation in 1957 and complete demolition, 1959-60.

A tram track brought building materials on horse-drawn wagons from the main railway line to the construction site.

The Recreation Hall (highlighted) on the top floor of the central block was open to the roof and could accommodate 900 people, or two badminton courts side by side.

A rare above-ground survival of this building, from the toilets of the centre south ground floor ward block (highlighted), shows cement plaster (with scribed outlines to resemble stone blocks) over brick.

The four million bricks were almost all made on site by James Gore, whose sons later established the Wingatui Brick and Tile works.

Breccia was used for window sills and stairs, Oamaru stone for window surrounds and other architectural details, and the roof was Welsh slate. Timber included Kauri and Jarrah.

In 1884 the building was criticised for being dark, and for the height of the dormitory windows preventing inhabitants from seeing anything but sky. Those on the first floor were lowered (highlighted) through the early 20th century.

Truby King’s timber picket fences were intended to enable a view of the countryside, replacing earlier corrugated iron airing courts.

Ground movement caused demolition of this replacement in c.1949.

Health and safety prompted demolition of the front part of the centre north ward block (highlighted), back to the main corridor/dayrooms in 1936 . . .

. . . and of the northern ward block (highlighted) in 1937-8.

. . . Or nearly. Part of the south wall of the northern block survives, and its Breccia stone window sills, and ongoing land movement, are still visible.

Each Oamaru stone step to the crow-stepped gables was large enough to stand on. The central block turrets, gables and chimneys (highlighted) were demolished in late 1945.

Despite its extra deep foundations, the tower developed cracks and followed in early 1946.

In 1956, it was hoped that strengthening works could extend the building's life by another 20 years.

Instead, close inspection led to evacuation in 1957, followed by demolition.