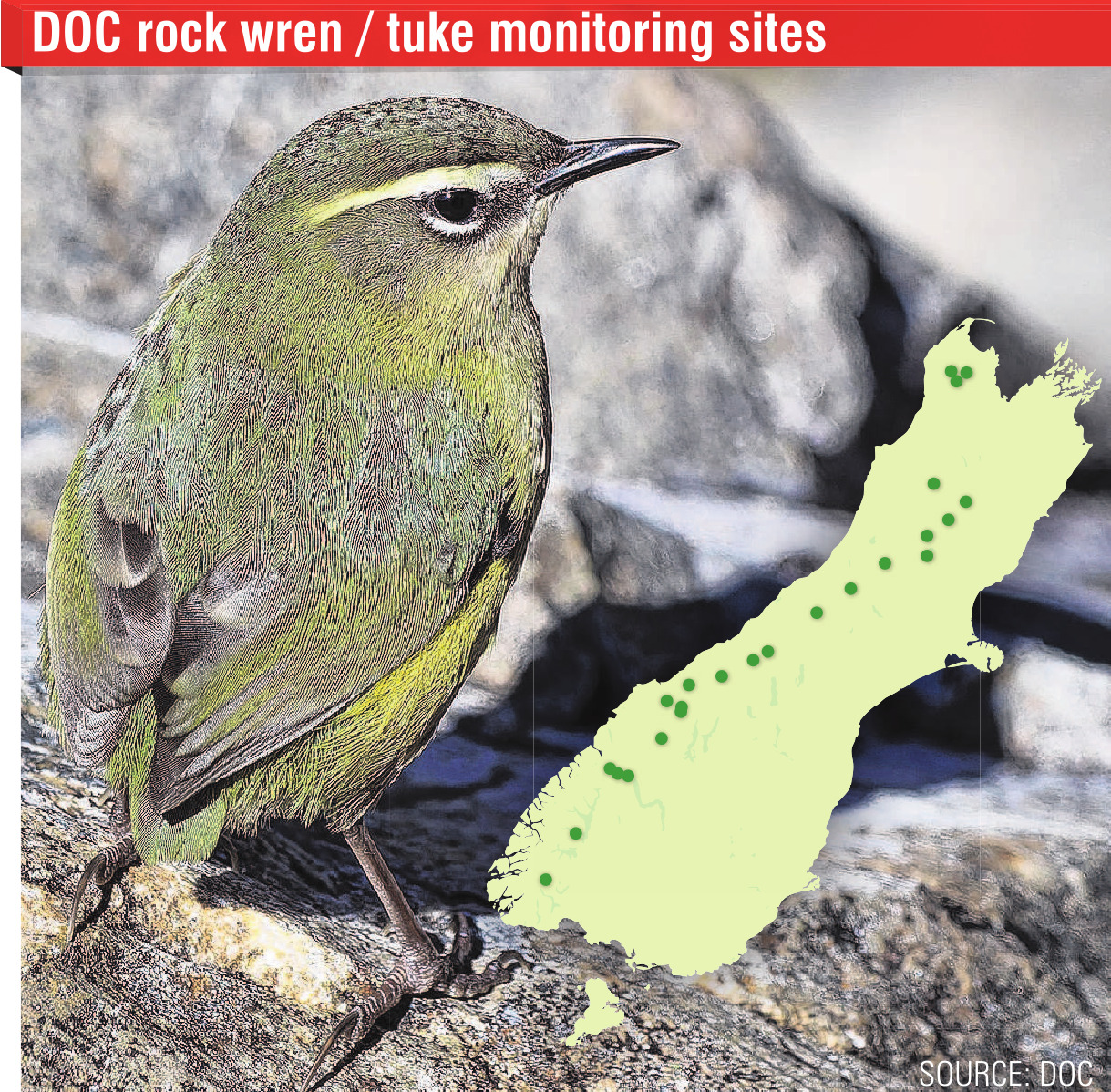

The Department of Conservation has monitored rock wrens across the South Island for the past five years to see how they fare both with and without predator control using methods such as trapping and aerial 1080.

Rock wrens live in Mount Aspiring National Park, the Kahurangi National Park and other alpine areas in the Southern Alps/Kā Tiritiri o Te Moana.

Each summer since 2019, Doc researchers have surveyed rock wrens at 25 sites ranging from Fiordland to Kahurangi.

There are 19 monitoring sites where rock wrens are protected through predator control and six sites where there is no management. Monitoring frequency has now been reduced and sites are now visited every two years.

Three of the rock wren monitoring sites are in Mount Aspiring National Park (MANP), two where there is predator control and one without.

Doc science adviser Tristan Rawlence said the MANP sites were last monitored in the summer of 2022-23 summer and would be monitored again this coming summer.

Monitoring from all the southern sites showed rock wren numbers were mostly increasing where predators were regularly controlled but gradually declining at unmanaged sites, he said.

"On average, there are more than double the number of rock wrens in areas with predator control compared to areas without.

"Stoats can be common in alpine areas and we’re increasingly seeing rats in this environment too, possibly due to warmer temperatures."

However, this was not the case with the small, reasonably stable rock wren populations in MANP.

"Unlike other areas where we have seen rock wren populations increase quickly because of predator control, monitored rock wrens in MANP are not increasing. This is likely because the predator control method is not yet optimal at these sites," Mr Rawlence said.

Rock wrens hop and flit rather than flying and nest on the ground, making them easy prey for introduced predators such as rats and stoats. They are threatened with extinction.

Mr Rawlence said after five years of monitoring data, it was now possible to see which predator control methods were of most benefit to rock wren.

"We’re seeing the best results where we’re using aerial 1080 in the alpine area above the tree line, where rock wrens live year-round, and not just in the surrounding forest.

"We’ve also learnt we need to control predators whenever the beech forest seeds, as predator numbers soar in response to more food."

Mr Rawlence said this method was applied in the Makarora predator control operation over 36,395ha in autumn this year, extending the operation into the alpine area.

"We will be monitoring rock wren in MANP this coming summer and look forward to seeing the result of changes to the predator control on rock wren in this area," he said.

Mr Rawlence said previous research showed rock wrens produced three to five times as many chicks when predators were controlled.

A study in Kahurangi National Park over four years showed 58% of rock wren nests were successful in fledging young following aerial 1080 predator control, while just 13% were successful without.

The rock wren monitoring programme is part of Doc’s National Predator Control Programme, which protects the most at-risk wildlife and forests across New Zealand’s public conservation land.

Rock wrens belong to an ancient lineage of New Zealand wrens that once included seven species. Today, only the rock wren and rifleman/titipounamu survive.

In the South Island, northern and southern rock wren populations have been found to be genetically distinct.

The northern birds are assessed as more threatened (classified as nationally critical under the New Zealand Threat Classification System) than the southern ones (classified as nationally endangered).