The study, run in collaboration with the Department of Conservation, is showing the ability of rats to multiply rapidly following beech seeding, such as the "mega mast" (mass seeding event) in 2019.

Scientists are hoping that understanding how altitude and food availability regulate rat numbers will give conservationists the edge in protecting wildlife from rat plagues.

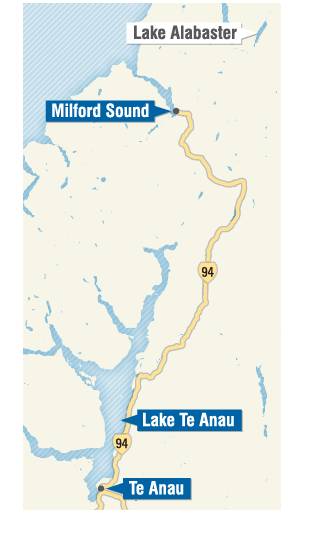

Since the study began 14 months ago, 912 individual rats have been live-captured in cage traps near Lake Alabaster.

Researchers give each rat a unique ID by inserting a microchip under the rat’s skin, like the type used for pet dogs, and placing a metal tag in their ear. Each rat is then released. While releasing a rat goes against the grain for most conservationists, the team can then calculate how many rats live in an area by looking at the proportion of marked and unmarked rats they capture.

Study leader Dr Jo Carpenter said the preliminary results were "startling".

Following the 2019 beech seed mast, rats at Lake Alabaster reached a "phenomenal" 17 rats per hectare.

These were some of the highest rat densities ever measured on the New Zealand mainland, and reflect the ability of rats to multiply rapidly after beech seeding.

Rats were generally less common in cold, high-altitude forests across New Zealand than in warm, lowland forests, Dr Carpenter said, but it was not clear whether that was because of the temperature or because of typically less food higher up.

To tease those factors apart, the team of researchers has been intensively monitoring rat population dynamics at both high and low elevations at Lake Alabaster.

Rats at high elevation are being fed to see whether they can survive cold temperatures when they have sufficient food.

Manaaki Whenua researcher Dr Adrian Monks said that was a particularly relevant question.

"Because if it’s temperature that normally limits rats from living up high, and not food, we might expect to see high elevation forests supporting more rats as the climate warms.

"This could have devastating consequences for some of our birds, which currently use these environments as refugia from pests."

Dr Carpenter said the research so far had shown it seemed food helped sustain the rats through the autumn.

"When we reached winter, though, the fed rats declined as much as the rats we didn’t feed. This suggests that another factor — perhaps temperature or predation by stoats — is limiting rats."

A key aim of the study is to help predict what rats will do based on the climate and forest at their site, allowing rat control to be done as effectively as possible.