Otago is the region third-worst affected by wilding conifers in New Zealand.

A national assessment of risk commissioned by the Ministry of Primary Industry (MPI) in 2016 showed approximately 70% of the Otago region as very highly vulnerable to wilding conifer infestation. This means that if nothing is done to prevent it, most of the low-intensity use land in Otago could be covered by exotic conifer forests within the next few decades.

This would have a serious impact on farming and especially for the hundreds of thousands of hectares of hill and high country land under low-intensity pastoral use. Livestock cannot be farmed under pine forest.

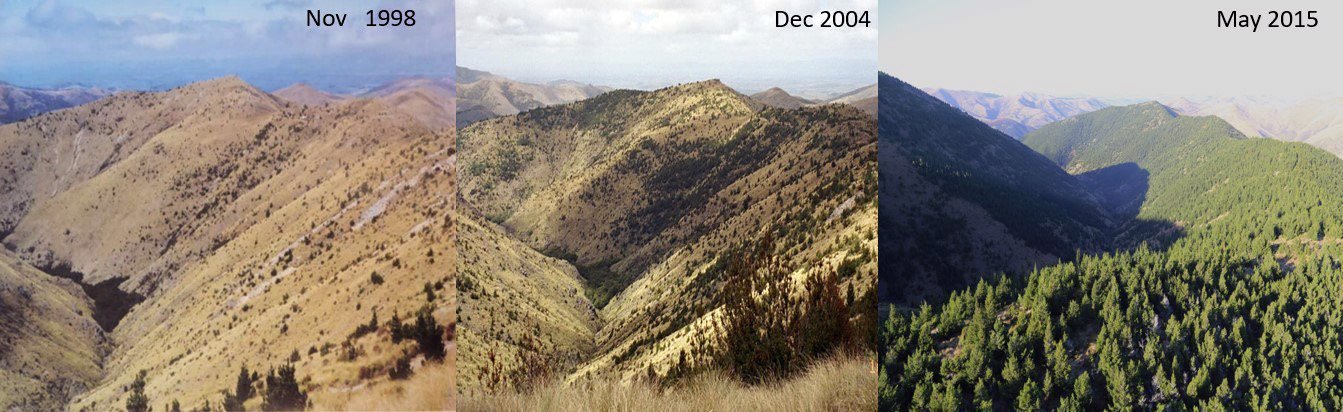

At present this is not a significant problem, but it could be in future because exponential spread and growth of wilding conifers can transform an open grassland into closed canopy forest within a few decades.

Unchecked wilding spread poses major threats to biodiversity and native ecosystems. Today some of the most dramatic examples of biodiversity impact are seen around Queenstown, where introduced conifers have been aggressively spreading since the 1950s. There is clear evidence here that wilding conifers can invade and disrupt subalpine grasslands and even montane beech forests. This will have huge consequences for land managed by the Department of Conservation across Otago in the future.

As wilding conifer infestations expand and infill, they have been shown by scientific studies to reduce water yield in catchments by up to 40%. If closed canopy wilding forests were to occupy the upper catchments of rivers like the Manuherikia and Taieri, this would have serious implications for the levels of water they provide. Users need to be clearly aware of this medium-to-long-term threat to their water resources.

The devastating fires at Lakes Tekapo (August 2020) and Ohau (October 2020) have greatly increased awareness of the additional risk that wilding conifer infestations can create for landscape scale wildfires. The increasing prevalence of wilding trees and forests in and around many of the populated parts of inland Otago must be a wake up call for everyone living in those areas.

The impacts of wilding conifers on social and cultural values have been eloquently described by Sir Grahame Sydney. As one of New Zealand's foremost artists he, with many others, cherishes the unique and special character of Central Otago’s rugged golden landscapes. He is deeply concerned by the prospect that these could be totally despoiled by blanketing cover of wilding conifers. Queenstown Lakes District Council (QLDC) has also recognised the negative impact of uncontrolled wilding spread across the iconic vistas that form the foundation of the tourism industry there. It has done this by strongly supporting the local wilding control programme for well over a decade now.

Despite these alarming scenarios, there has been major progress made with the control of wilding pines over the last 20 years. This began in earnest when in 2016 the Government, through MPI, started to fund the national Wilding Conifer Control Programme. The 2020 Jobs for Nature budget provided $100 million over four years for wilding conifer control. Today over 2 million ha of wilding-affected land across New Zealand has been treated.

The recent funding provided has allowed the two community-led groups in Otago (Wakatipu Wilding Conifer Control Group and the Central Otago Wilding Conifer Control Group) along with their agency partners (MPI, Doc, Land Information New Zealand, Otago Regional Council, QLDC, Central Otago District Council) to make major progress towards stopping wilding spread in many parts of the region. With the momentum created over the last six years by the programmes, Otago should be well on the way to achieving wilding-free landscapes within the next decade.

It needs to be emphasised that wilding conifer management is complex and time consuming. Critically seed can remain viable in soil for several years until it breaks down. Therefore, where coning trees have been cut down, it is necessary to undertake at least two further cycles of maintenance control 3-5 years apart to exhaust the seed bank. So, once a control programme is initiated, it will generally take 10 years or more to achieve a sustainable outcome.

Unfortunately now, just when programmes are starting to succeed, the Government’s funding — which has driven this progress — will run down in 2024 to a national baseline of $10 million a year. This will mean around 60% reductions for the highly successful programmes in Otago. Effectively, the lower funding means the programmes here will go backwards and the investments made to date will be lost.

If additional national funding of around $15 million per annum could be found for the next 10 years, it is likely that the wilding programmes in Otago and elsewhere could be completed in an effective and orderly way. If not, in future it will cost tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars to claw back the lost ground.

New Zealand’s history is littered with biosecurity mistakes and lost opportunities that have cost us dearly. Wilding conifers should not be another of these.

— Richard Bowman is chairman of the Wilding Pine Network