Notwithstanding the very real benefits and social imperatives of helping students from relatively underprivileged backgrounds through tertiary education, the Government's intention to claw back eligibility for student allowances, and to increase the rate at which interest-free student loans are repaid, does address the problem of steadily rising debt.

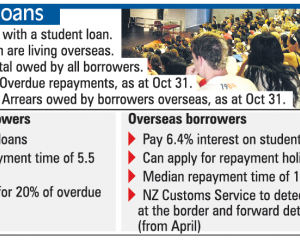

Total student debt is now about $12 billion.

In 2007-08, the total cost of the allowances scheme was $385 million; by 2010-11 it had risen to $620 million.

In March, the Government froze the parental income threshold for allowances, maintaining it had increased ahead of wage growth and inflation.

Unfortunately, one effect of this may be to prevent a number of needy students from continuing their education, particularly when employment possibilities are so demonstrably few.

And while the general thrust of the Government's initiatives makes sense, cutting off the allowance system at four years, as was proposed last week, is potentially counter-productive.

Medical, dental and post-graduate students, whose courses of study routinely take them beyond the proposed four-year limit, will suddenly be unable to apply for support.

This will, of course, affect mainly those from underprivileged backgrounds who cannot count on family money - since the student allowance system is already means-tested against parental income.

Last week, Tertiary Education Minister Steven Joyce also set out changes to the student loan repayment rate: beginning next year, this would be increased from 10% to 12% for any earnings over $19,084.

The effect of this would be that a person earning the average wage of $923 a week would pay back $66.90 a week instead of $55.80, on top of an income tax of $114.40.

This additional impost may prove an added incentive for young graduates to join the brain drain and depart New Zealand's comparatively low-wage economy for Australia where they will earn wages that better enable them to pay off their loans.

On the one hand, it will mean the loans will be paid off sooner; on the other, the Australian economy will benefit from the education in part funded by the New Zealand taxpayer.

The Government is faced with a delicate balancing act.

Twelve billion dollars, and rising, is an extraordinary level of indebtedness.

Furthermore, an estimated $2.3 billion is held by New Zealanders now living and working in Australia and the United Kingdom.

Last year, the Government announced it would use debt collectors to chase up some of this offshore debt.

It also cut the three-year repayment holiday period for offshore borrowers to just a year.

These were welcome and justifiable moves.

In March this year, Prime Minister John Key ruled out re-imposing interest on student loans - putting it in the politically-too-hard basket.

A loan of $50,000 which now might take eight years to pay off, with interest added, would become a $90,000 loan and take up to 15 years to pay off, he said.

And he was right: the debt burden of students is already extremely high and when added to the cost of housing in New Zealand it is difficult to see how many young people can get on to the home-ownership ladder and begin families; and conversely why so many leave for the more lucrative or exciting pastures of Australia, the United States, or the United Kingdom - taking their student debts with them.

The answer must be to imbue the coming generations with a wariness of excessive debt and to get them to take a more responsible attitude towards repayment.

But care also needs to be taken in getting the allowances and repayment equations right.

Raising the standards of education across the board is rightly seen as being one of the best avenues to address poverty, social inequality and crime in this country, while at the same time stimulating flexible, innovative, research and design-led sectors of the economy so necessary to complement our primary export industries.

Tightening up on student allowances, and increasing the rate at which loans must be repaid, may help to establish a new reality among those who all too readily acquire the State's cheap money to study, but it is a strategy that also carries serious risk.