The Treaty of Waitangi has become, perhaps, the most divisive of all current political issues. And like the other topic, taxation, political parties have generally taken rigid postures from which any movement or compromise is regarded as a defeat, a betrayal, or worse. Of the governing parties, Act and NZ First are vehemently antagonistic to the Treaty and its possible ramifications, one on straight-forward ideological grounds and the other possibly because a secure source of conservative support lies there. The National Party seems agnostic, though it too is aware of its conservative base.

Opposition parties, Te Pāti Māori and the Greens, are strident in their support, to the point in some cases of asserting wholesale constitutional change. The Labour Party, though quite clear on which side of the debate it stands, is less strident and not so much ambivalent as occasionally a little less than candid. Its muddled mishandling of the question of co-governance, for example, has exacerbated the very problem it was meant to resolve.

It all comes down, then, to what does the Treaty mean, and to whom? I will take my lead from Dame Anne Salmond, whose authority seems unexceptionable. But first I would like to comment on one apparently popular notion that demonstrates the theme.

Anaru Eketone (ODT 18.12.23), arguing for the primacy of the te reo version of the Treaty, asserts, "It was their [Māori Chiefs’] document, outlining the terms they had put forward, and it defined what they would offer to allow British Government in New Zealand".

The implication here is misleading. First, it fails to consider the origins of the Treaty, including its initial translation into te reo, and the efforts of the Missionary Society, among others, to establish some means of mitigating lawless European intrusion into the lives of the native people and to address inter-tribal warfare, exacerbated by the availability of muskets, which had taken an appalling toll on the local population.

Second, does anyone seriously believe that with no Treaty the European diaspora, uninvited, would have passed New Zealand by? Whether in subsequent years the Treaty had much material effect is, of course, arguable, but without the imposition of British law, as flawed and flouted as it might have been, the consequences would surely have been rather different.

Eketone’s assumption that Māori "allowed" the British to assume governance suggests, at least, the insidious and divisive, but now commonplace distinction between "tangata whenua" and "tangata Tiriti", the latter being somehow beholden to the former for their very existence.

Dame Anne Salmond ("Māori and Pākehā think differently", Newsroom, 14.12.23) notes that David Seymour objects to the Treaty’s "collectivist" rather than "individualist" principles. That is, he reflects a European tradition of thought that goes back to Descartes and results in a world-view of binary opposites, analytic logic and the primacy of the thinking individual (cogito ergo sum).

The traditional Māori world-view, on the other hand, is "relational"; i.e. "the world is organised through whakapapa into complementary pairs [which] order reality into dynamic relational networks, expressed in the language of kinship."

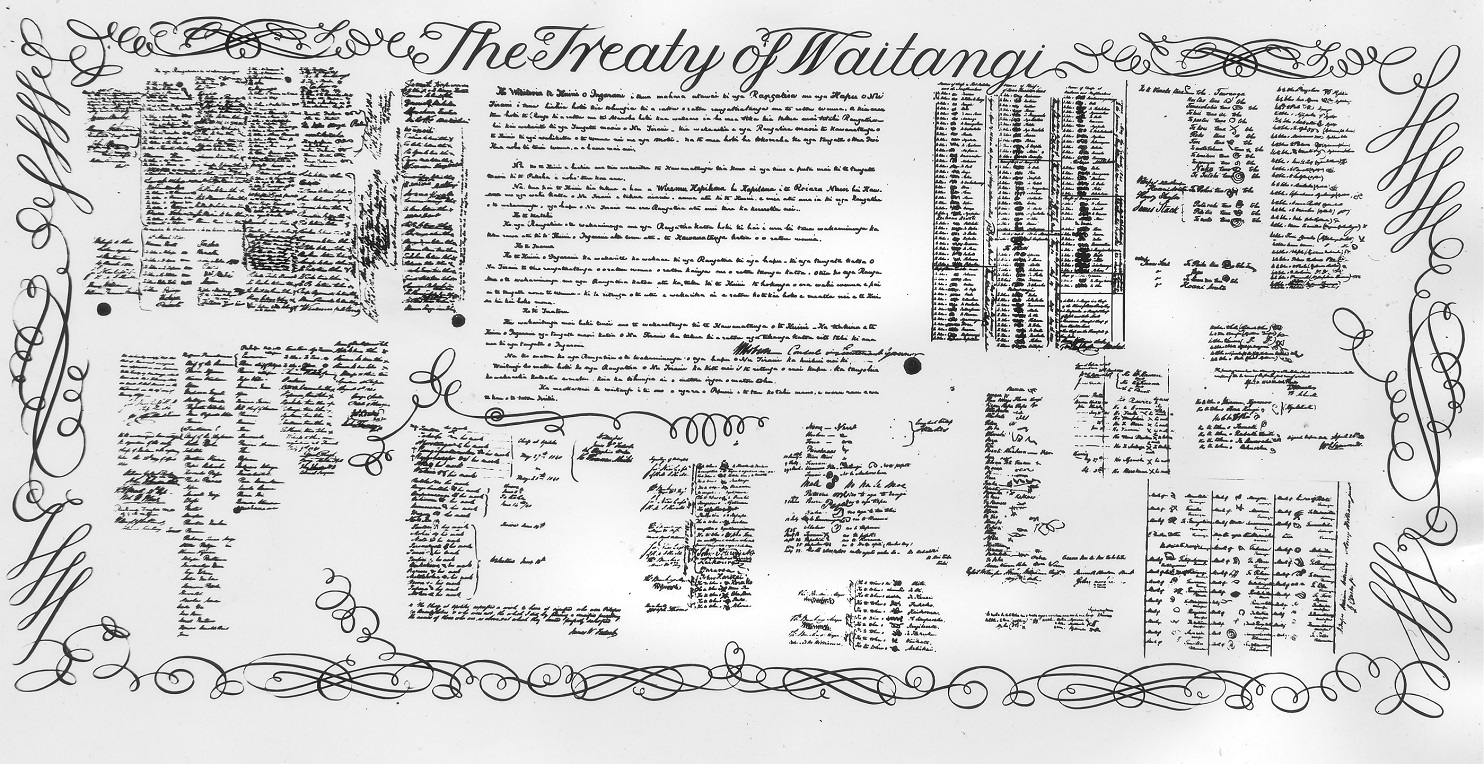

The point is the document signed by rangatira in 1840 is understood as relational, "neither individualist nor collectivist, but a kin-based combination of both, expressed in the language of chiefly gift exchange".

The dynamic of the Treaty, then, is manifested in the exchanges defined in its various parts and, importantly, its parties: the Queen of England, the rangatira and the hapu of New Zealand.

In the first article, "rangatira give (tuku) to the Queen of England absolutely and forever all governance (kāwanatanga) of their lands."

In the second, the Queen ratifies and agrees that "hapu and all the inhabitants of New Zealand [maintain] the tira rangatiratanga (absolute chieftanship) of their lands, dwelling places and taonga".

In the third article, "in exchange for the agreement to the governance of the Queen, [she] promises to care for all the indigenous inhabitants of New Zealand and gives to them all the tikanga exactly equal (rite tahi) to her subjects, the inhabitants of England".

This, I hope reasonably accurate, summary is necessary to support two important points. First, the agreement is not between two "races", but between Queen Victoria and rangatira, who each reserved the right to make their own decisions about relationships — some, for example, fought with and some against British troops in the land wars. "While early settlers constantly referred to the Māori race ... it was a long time before hapu saw themselves in that way."

Dame Anne continues, "Like an individualist reading of Te Tiriti, a collectivist reading — one that defines Te Tiriti as a ‘partnership between two races’ or ‘between Māori and Pākehā’ (a classic case of Cartesian dualism) as in the 1987 Lands case, for instance — is mistaken, ignoring this fundamental diversity of interests and views."

And, one might add, the He Pua Pua document, outlining a plan for Māori sovereignty, is itself a product of this same European mode of thought.

Second, the irony of this underscores a very significant fact — that in almost 200 years, modes of thought and language as well as population and political and social institutions have moved on from the meeting of world views in 1840. The individual as a locus of value and a keystone in modern concepts of freedom is out of the bottle and won’t be put back. But the analytic logic that has given us modern science, while obviously beneficial in many respects, is, however, inadequate for the exigencies of social and political life.

The simplistic, abstract, purist liberal concept of freedom is clear confirmation of that. It’s a zero sum game, so that when some get more of it (employers, for example), others (employees) get less.

I’m not suggesting we clear the decks and imbibe the thoughts and beliefs of 1840s rangatira. We can’t. Our language and experience prevent it. We can, though, rediscover, because they are not new, the relational politics and economics that is the other half of Western political history. In fact we are being forced to do so to counter the social and ecological damage caused by unfettered individual "freedom", either corporate or personal.

The conclusion seems to be, then, that for a government to honour the Treaty, especially Article 3, and to allow its citizens the freedom to "be themselves", it needs to give them the social and economic space to do so: freedom that comes with work, housing, health and education. Which brings us back to tax policies and the Labour Party.

- Harry Love was the chairman of the Castle St branch of the Labour Party in 1987-88, and the New Labour parliamentary candidate for St Kilda in the 1990 election.