Bruce Munro talks to telegraph workers about communications before telephones triumphed, chats to Snapchatters who constantly communicate but rarely call, and asks, is it OK that we are going back to a future of less talking?

TWO men sit, framed by the large lounge window of a pristine, mid-century, brick and tile, Dunedin beach suburb home.

The older of the pair, Iain Graham, the host, is a sprightly nonagenarian.

Graham began his telegraph career in Dunedin the year after World War 2 began.

"The changes since I started as a telegram delivery boy ... you just can't credit it,'' he says.

Facing him, Graeme Reid, who at 69 is 25 years his junior, nods as he holds a smartphone in one hand.

"There's more computing power in this than there was in the whole moon landing. And you carry it around in your pocket. It's just unbelievable,'' Reid, also a former telegraph worker, says.

In 1969, when Neil Armstrong bounced off the Apollo 11 ladder on to the lunar surface - uttering the eternal words "One small step for man; one giant leap for mankind'' to a worldwide, live, television audience - voice calls were on a skyward trajectory.

At the time, Graham was a senior supervisor in the Dunedin telegraph branch - the local outpost of the prestigious, state-run conglomerate, the Post Office. On the second floor of the imposing Chief Post Office building, just south of the Exchange, in Princes St, he had responsibilities for the thousands of telegrams that poured through the telegraph office every day.

For a century, telegrams had been the main form of telecommunication. But by the late-1960s, new technology was reshaping the landscape. A decade earlier, there were 500,000 phones in New Zealand. In 1969, there were about 750,000. Another decade on, there would be more than a million telephones, and telegrams would be on their last legs.

Now, it's five times that figure. There's a phone for every man, woman and baby; landline phones are fast becoming museum pieces; and, telegraph office staff are about to mark the 30 years since the last telegram transmission.

Yet, despite how divergent the worlds of telegrams and smartphones appear, there are some surprising parallels.

Morse code is how messages were sent and received when, in 1940, the 16-year-old Graham, wearing his navy-coloured, telegraph message boy uniform, complete with tunic, cap and bicycle, began delivering telegrams throughout inner-city Dunedin.

"You were encouraged to learn the Morse. You couldn't get promoted far without it,'' he recalls.

Learning took him as far as Fiji, where he served for two years during World War 2, and to the heights of Invercargill telegraph branch manager, from which he retired in 1981.

All these years later, he still has an essential piece of early telegraph equipment. With one hand he cradles a Morse key - a beautiful piece of wood and metal machinery. With the other he demonstrates how messages were sent by lightly, fluidly tapping a series of short and long strokes.

Each Morse operator had their own distinctive rhythm, which experienced, fellow operators could instantly recognise, even as they translated the aural dots and dashes into death notices, wool prices, money orders, chess moves, rugby results, newspaper stories, wedding greetings, tourist bookings ... anything and everything that people needed and wanted to communicate.

TODAY, many will be discombobulated by the suggestion Morse and the social networking app Snapchat share a family resemblance. But, look closer.

This month, it was announced that the United Kingdom had reached a telecommunication pivot point. For the first time since Alexander Graham Bell was granted a United States patent for the invention of the electronic telephone, in 1876, the number of voice calls fell in the UK.

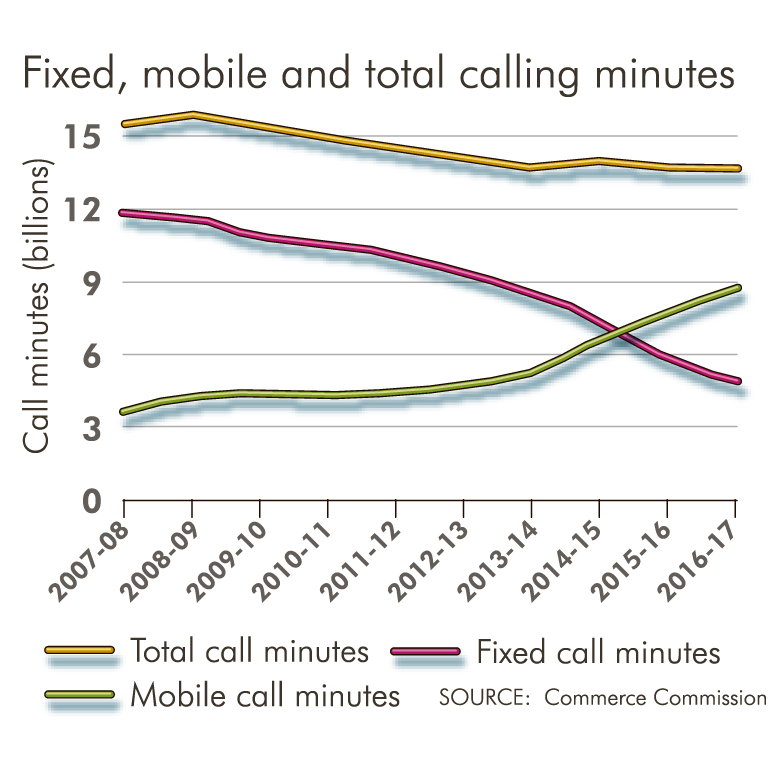

New Zealand, it turns out, is ahead of the (Bell) curve. Here, the number of minutes spent talking on mobile phones has been climbing vigorously for the past four years. But fixed (landline) call minutes have been dropping for at least a decade. Combine the two, and the total call minutes peaked during the 2007/08 financial year.

Since then, the total amount of time we spend chatting on phones has been gracefully declining, according the the Commerce Commission's (ComCom) 2018 telecommunications market report.

But if Kiwis are talking less on phones, it certainly is not because they have given up communication devices.

THERE is at least one phone for every person in New Zealand. The average household has eight video-capable devices. And the demand for mobile data is booming.

Tellingly, the biggest user of data worldwide is not video streaming services - YouTube comes in second at 24% - but social networking, at 29%.

That is Facebook, WeChat, WhatsApp, Instagram, Twitter ... That's communication. But, increasingly, not of the verbal kind.

Last year, US teenagers rated Snapchat their most important social network. Anecdotal evidence suggests it is a similar picture here.

And Snapchat, despite having a moniker that strongly connotes people engaged in pithy conversation, is much more about sending and receiving endless images of puppy-eyed people vomiting rainbows rather than any actual talking.

That might be a bit harsh. But the app is certainly primarily about photos and short videos rather than verbal communication.

Nathaniel Morris (22) says he uses Snapchat because it is "a good, easy and quick way to keep in contact with friends and family''.

"Normally when I use Snapchat, I'll share quirky or cool things that I'll see during my day; perhaps a nice sunrise, a nice car, a street performer ...'', says the IT worker, who recently shifted out of Dunedin for his job.

A distinctive feature of Snapchat is streaks.

Streaks are a string of images sent at least once every 24 hours and replied to within the same period. The longer the string, or streak, the better.

Cody Finch (15), of Balclutha, has concurrent streaks running with 43 different people. About half of them have been running for more than 200 days.

Longer streaks get rewarded with special emojis. Rites of passage include, the red heart emoji for two friends who have been sending more snaps to each other than to any of their other friends for two weeks straight, the "100'' emoji for streaks of that many days and the fabled mountain emoji for extremely long streaks.

Finch, who is a year 11 pupil at South Otago High School, estimates he sends dozens of Snapchat images each hour during waking hours.

"It could be anything. It might just be a photo in class of the wall, or yourself or a mate.''

The aim is simple - getting someone to reply. Connection. Belonging.

Mosgiel mother of four, Alicia Johnson (30), uses Snapchat several times a day. She sends photos of her children to her mother and to her partner when he is at work.

She also has a streak running with her friend, Scott McLeod. A 927-day streak. He tends to send her a snap while out for early-morning walks. She replies sometime before lunch.

"He's a good friend. We keep the streak going because it's so high and we don't want to lose it,'' Johnson says.

Snapchatting Morris says he does not make many phone calls to family and friends.

"The only person I would regularly call is my grandfather.

"With [social media apps or texting] I can send a message to someone, and they can read and reply at their leisure. When it comes to making voice calls, it can be a pain if the other person is busy.''

LIKE the days of Morse, voiceless communication is clearly making a comeback.

Another voiceless, back to the future, characteristic of 2018 telecommunications is machines talking to machines.

By 1965, when Reid completed telegraph training school and began working in the Dunedin office, keyboards had replaced Morse.

The new system was called machine printing.

The telegraph operator entered the telegram message using a keyboard. A machine turned the words and letters into a five-digit code and punched corresponding holes on to narrow tape that automatically fed into a transmitter. In the telegraph office closest to the telegram's intended recipient, a receiving machine turned the code back into alphabet strings, which it printed out on a continuous strip of gummed tape. The receiving telegraph operator simply cut the tape to lengths and stuck them on to yellow telegram forms.

The finished telegrams would be picked up by a distributor circulating around the office. They would be stamped and numbered and then popped into one of the ingenious Lamson vacuum tubes, which would whisk the telegrams down to the busy, basement dispatch room.

In the end, Reid did himself and his fellows out of work. He became a telex liaison officer, helping businesses install their own telephone network machines, making telegraph officers superfluous.

"I loved it. But I didn't realise I was killing my own job,'' he says.

When the last Telecom telegram was sent on August 31, 1988, not many, beyond the redundant staff, cared.

For the former employees of the Post and Telegraph/Post Office/Telecom behemoth, it had been a great workplace; a protective, generous, extended family. That is shown by the 40-odd former Dunedin telegraph office workers gathering from far and wide for the end-of-month, 30th anniversary reunion.

For most of the public, however, telegrams were quickly forgotten. It was so much easier, quicker, to pick up the phone and give someone a call.

In 2018, however, the same impulse for convenience and time-saving is leading the way back to machines talking to machines.

One of the most significant developments in telecommunications right now is the Internet of Things (IoT).

Increasingly, every conceivable object is being kitted out with the ability to log on to the internet and talk to other internet-capable objects.

This year, Spark and Vodafone have each launched IoT networks.

The potential is limitless. Public rubbish bins can be made to tell city council computers when they need emptying. Sensors on cows can keep a farmer's computer updated on the animal's location and body heat. There are already fridges that can write your shopping list. It will not be long before they are phoning it through to your local supermarket.

That is no joke. In May, Google demonstrated new technology that will allow users to direct their phone to, for example, call a restaurant and make a reservation. It does so with the ability to engage in a range of conversation, and with such a natural sounding voice, that restaurant staff have no idea they are talking to a machine.

Called Google Duplex, it is likely to be in use later this year.

It is almost inevitable that restaurants will want a version that allows them to have their own human-sounding machine to take those reservations.

It might not be long before we do not need to talk to each other at all.

WHY are we going back to this future of trimmed verbage?

Certainly, saving time in often already-too-busy lives is one driver. Tapping an emoji rather than calling to reply just seems so much more efficient.

There also appears to be a new social mores among young people who seem hyper-sensitive about privacy. They put unheralded telephone calls, especially to people they do not see frequently, in the "bordering on invasive'' basket.

Messaging is the more respectful option in Millennial and Gen-Z telecommunication etiquette.

That, combined with the incessant contact social networking allows, explains why talking less is happening more, Mikayla Cahill says.

Cahill (23) is studying for a master's degree in media, film and communication, at the University of Otago. Her honours thesis topic was Instagram.

"Voice messages might be declining,'' she says.

"But ... the fact that most people are now online throughout the day [means] contacting them in a variety of non-intrusive, gentler ways, like private messages, is faster and convenient.''

Is the decline in speech a bad thing?

Not really, Cahill believes.

"Especially when you consider that the majority of our communication is non-verbal.

"Language is only a small part of how we interact and understand each other.

"Almost everything is non-verbal communication. There's body language, the types of music we listen to, the places we go in public, the types of clothes we wear - all of these communicate things about us to other people.''

"Thumbs up'', "winky face'' and "heart eyes'' to the bright future of the proud tradition of voiceless communication.

Hieroglyphs, here we come!