The presentation of illuminated addresses, decorated pages that mark special occasions or celebrate personal achievements, was once a popular practice in New Zealand.

The term "illuminated" refers to how the addresses were usually decorated with gold, silver or bright colours.

We have many illuminated addresses at Toitū. Some are plainer than others, comprised of skilfully drawn calligraphy. Others corral the text in a decorative design. Some are elaborate works of art embellished with drawn or painted scenes.

Alexander Miller was a builder, who in 1895-96 managed the construction of new premises for drapers and clothiers Herbert, Haynes and Co in Princes St. He’d been hired by his brother-in-law, Daniel Haynes, owner of Herbert, Haynes and Co, who had married Miller’s sister Margaret in 1864.

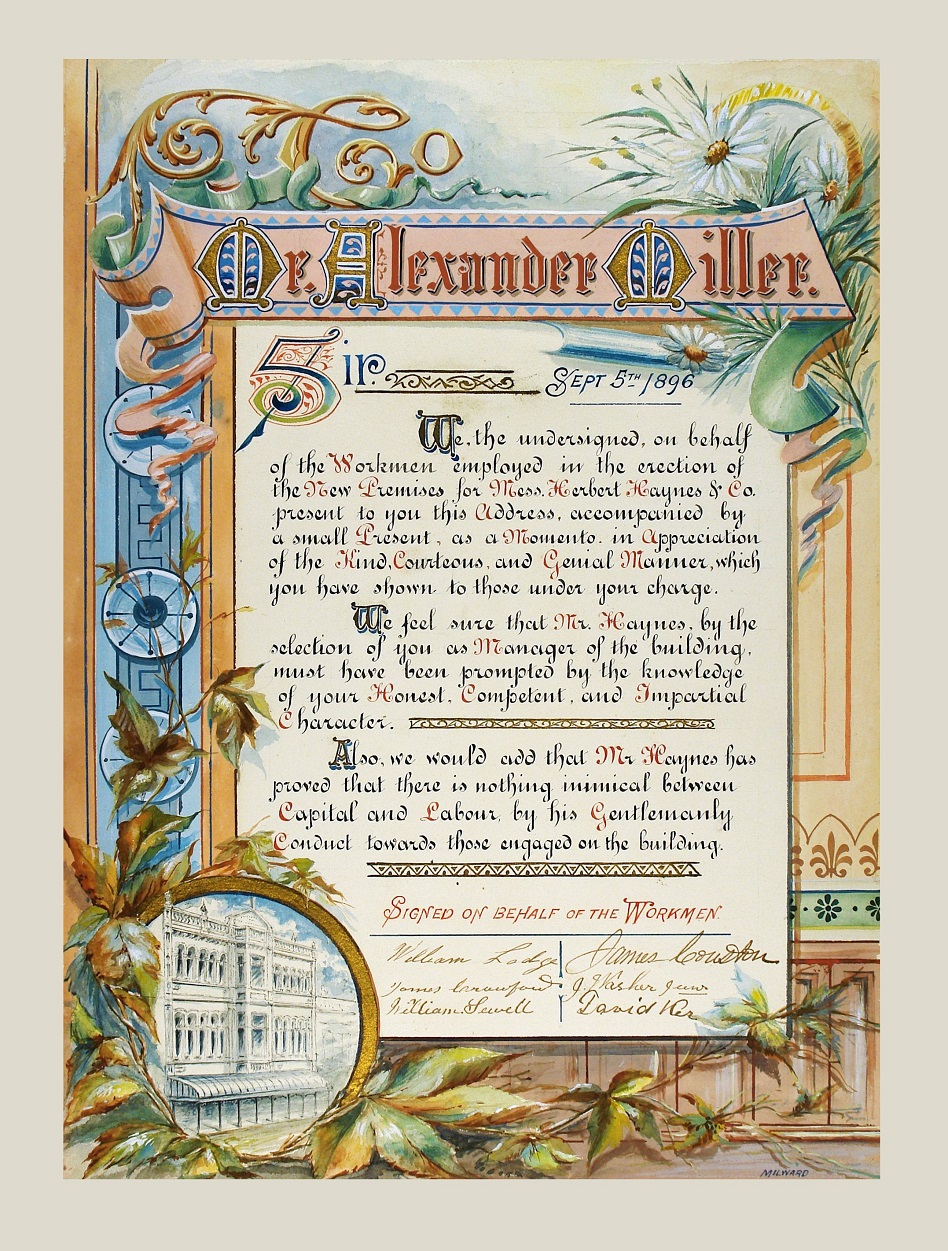

The address, which was produced by signwriter William Thomas Milward whose business was across the street from Herbert, Haynes and Co, reads:

To Mr. Alexander Miller.

Sir

We the undersigned, on behalf of the Workmen employed in the erection of the New Premises for Messrs Herbert Haynes & Co. present to you this Address, accompanied by a small Present, as a Memento in Appreciation of the Kind, Courteous, and Genial Manner, which you have shown to those under your charge.

We feel sure that Mr Haynes, by the selection of you as Manager of the building, must have been prompted by the knowledge of your Honest, Competent, and Impartial Character.

Also, we would add that Mr Haynes has proved that there is nothing inimical between Capital and Labour by his Gentlemanly Conduct towards those engaged on the building.

This adulation, however, belies the fact that just four months earlier a terrible accident had occurred under Alexander Miller’s watch at the construction site.

On May 4, 1896, four carpenters, including two who would later sign the illuminated address on behalf of the workers, were working on scaffolding that collapsed. Two had been securing a hanging bolt into the roof when the three-inch-thick Oregon plank that they were standing on snapped suddenly. William Lodge grabbed the hanging bolt and held on for dear life until he could be rescued with a ladder. Thomas Cole, along with the other two carpenters who had been standing on a cross plank, crashed to the ground. Cole broke some ribs and was sent to hospital, along with an unconscious Robert Kirkwood who had taken a severe blow to the back of his head. James Johnston sustained foot and back injuries in the fall.

Alexander Miller had been standing beneath the scaffold and leapt out of the way. He was presumably first to render assistance to the victims of what would later be judged to be a freak, and therefore blameless, accident.

About an hour and a-half after being admitted to hospital, Robert Kirkwood succumbed to shock and concussion. The 51-year-old carpenter, originally from Scotland, was married with six children, the eldest of whom was 17 or 18 at the time. His widow, Julia, relocated the family to Auckland in the wake of her husband’s death and had his remains shipped there for burial also.

This notice was placed in a Dunedin newspaper on the first anniversary of Kirkwood’s death:

In Memoriam

KIRKWOOD — In loving memory of Robert Kirkwood, accidentally killed May 4th, 1896.

All the plans of life are broken,

All the hopes of life are fled —

Counsel, comfort, and advisor,

Alas! alas! for thou art dead.

Dearest father, thou hast left us,

Here thy loss we deeply feel;

But ’tis God that hath bereft us,

He can all our sorrows heal.

— Inserted by his loving wife and children.

These sentiments were no doubt shared by many other families in an age where fatal industrial accidents were common.

Most certainly they would have been understood by the families of the 65 men who lost their lives in New Zealand’s deadliest industrial disaster at the Brunner Mine just six weeks before Robert Kirkwood’s fatal accident.

Peter Read is curator at Toitū Otago Settlers Museum.