The memories are still vivid, and the emotions still raw, 50 years on from the sinking of the passenger ferry Wahine.

Reporter Chris Morris speaks to three men with Otago links - a crew member, a passenger and a rescuer - about New Zealand's worst modern maritime disaster.

Stan Spiers still chokes up when asked to remember Wahine.

He's 75 now, retired, and enjoying the comfort of the late summer sun streaming into his Port Chalmers home.

But his mind is elsewhere, conjuring memories of the shrieking wind and towering waves that claimed Wahine, the lives of 51 people on board on the day, and, very nearly, his own.

The memories are still vivid, and his voice cracks with emotion as he reflects on next week's 50th anniversary."I suppose it's a part of history and I'm probably lucky to be here. Because a lot of people aren't,'' he says, his eyes glistening.

On April 10, 1968, Mr Spiers was aged 25 and six weeks into a new posting as an engineer on Wahine when chance placed him in the storm's path.

He was due to leave the ship in Lyttelton the day before the disaster, to join a new ship in Port Chalmers.

"I was going down the gangway with my suitcase and the second engineer yelled out to me 'Spiers come back. Your boat's running late and they want you to do another trip'.''

By the next morning, he was cradling a cup of tea in his cabin as the storm built.

Wahine, carrying 734 passengers and crew, was crossing Cook Strait to Wellington just as Cyclone Giselle, travelling south, collided with a southerly front heading up the country.

About 6am, as the ferry reached the narrow entrance to Wellington Harbour, the wind suddenly intensified from over 50 knots (92.6kmh) to more than 100 knots (185.2kmh).

Shortly after, a huge wave - estimated to be 45 feet (13.7m) high - slammed into the ship, which broached and heeled over dramatically.

"That was when the disaster started,'' Mr Spiers recalled.

He raced down to the ship's boiler room and a desperate battle followed, as Captain Gordon Robertson and the ship's crew tried unsuccessfully to turn the ferry's bow into the waves.

But, with the ferry's propellers lifting out of the water, it was slowly pushed towards Barrett Reef, a rocky feature at the harbour entrance.

At 6.35am, with Wahine's radar down and visibility poor, Captain Robertson ordered full astern.

"Then there was a great shudder and a bang. We were on the reef,'' Mr Spiers said.

FOR Russell Stewart, a Dunedin accountant, the memories of Wahine have also never faded.

He was a member of the University of Otago cricket team travelling on the ferry from Lyttelton to Wellington for the Easter tournament.

A crew member had warned him the night before of a "rough journey'' ahead, so Mr Stewart had opted for an early

night on board.

He was showering the next morning when the Wahine hit the reef, throwing him to the side of the cubicle.

Passengers were ordered up to B deck with life jackets on, which came as "a bit of a shock'' but also prompted a few sarcastic comments about the steamship company, he said.

The quips ceased when the passengers got to B deck and "looked out and saw the storm''.

"It was almost outrageous,'' he recalled.

"You couldn't actually see any water. The sea was so much churned up, it was just foam . . . the wind, it was horrific.''

The passengers were kept in a lounge, playing cards and being reassured by crew, until about noon.

"All of a sudden . . . the ship just listed violently to the starboard side. All the tables, chairs, people, just ended up on the low side.

"We all crawled back and then 10 or 15 minutes later, the same thing happened again.

"It just got worse and more frequent.''

IN the engine room, Mr Spiers and his crewmates were battling the cause of the roll - water flooding into the ferry's vehicle deck.

The weight of the water was dragging the ship over to one side, but it proved impossible to get the water down to the engine room, where pumps could have removed it, he said.

Eventually, the ship rolled over again "and did not come back'', he said.

About 1.30pm, alarm bells and announcements signalled it was time to abandon ship.

For Mr Spiers, sealed off by the engine room's watertight doors, his way out was an emergency hatch in the ceiling.

But the hatch led to the flooded vehicle deck, and the water above made it impossible to open.

Mr Spiers instead climbed into the ship's funnel and over hot pipes to reach another hatch that would open.

Once up on deck, the ship's "fairly steep'' list to starboard went "further and further all the time'', he said.

"People were sliding down the deck and getting injured . . . a few people broke arms and legs and things, or got banged up, when they hit the railing at the other end.

"Some of the people weren't waiting to get into a life raft. Some of them were jumping over the side.

"They [thought] they were saving themselves . . . but some of those ones got washed right out into the middle of the harbour.''

Mr Spiers helped passengers reach life rafts, including one young girl aged 4 or 5 he took from her mother, before being told to take command of a raft himself.

"I went over the side in that one.''

ON B deck, Mr Stewart recalled "a bit of panic'' and then errie silence after the order to evacuate.

A queue for lifeboats formed, and "it was like the old British tradition - women and children first''.

Mr Stewart and team-mate Stu Hunt were at the back of the queue and soon got sick of waiting.

"We decided to climb up to the high side and get out on the deck. Once I got out on the deck it was a real shock, because I saw all these people in the water in their life jackets.

"I thought 'Christ . . . this is actually the real thing'.''

The pair slid back down to the starboard side, only to find the lifeboats gone.

They were contemplating a plunge into the sea when a lifeboat full of passengers appeared, and they jumped from the Wahine.

IN Wellington, Steve Ellis and three colleagues were drinking in a Willis St hotel when news of the disaster broke.

Mr Ellis - a Christchurch man who worked for BP Oil in Dunedin after the disaster - and three friends had just been discharged from the officer cadet training unit in Waiouru, and were to board Wahine for the trip south.

But they had a day to fill in first, and after 12 weeks in the army "thought a few beers appropriate'', he said.

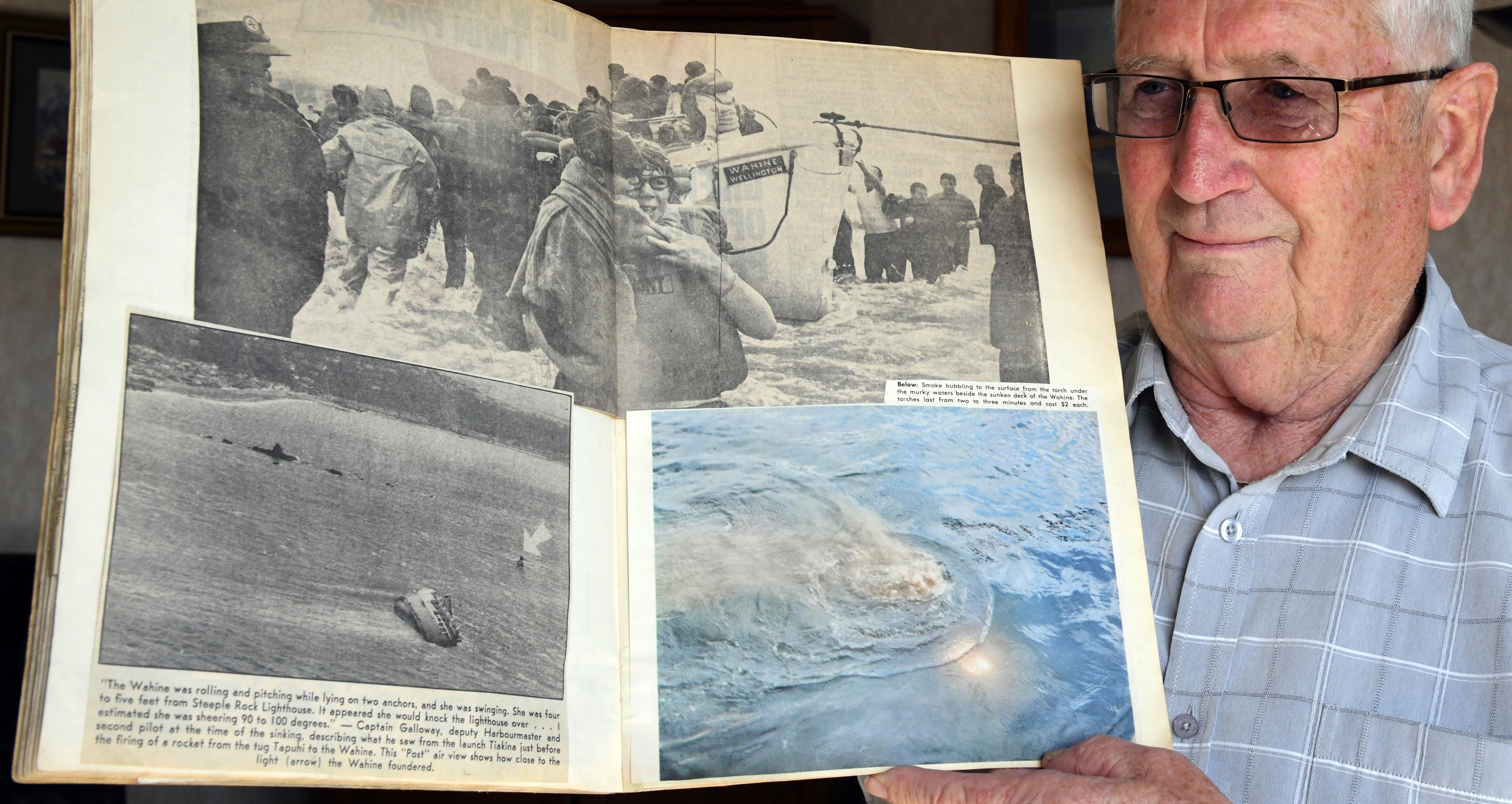

After hearing a radio report of the disaster, the four men took a cab to Seatoun wharf, arriving as the first survivors came ashore.

Still dressed in army uniforms, the four men were recruited for the rescue effort and spent hours helping survivors from the icy waters.

Afterwards they returned to their Willis St hotel, only to hear more passengers were coming ashore at Eastbourne, and decided to volunteer again, Mr Ellis said.

Approaching a police station in search of transport, they were directed up the road to an address where army trucks coming from Eastbourne would be returning to the scene.

The "address'' turned out to be a makeshift morgue, and the trucks coming from Eastbourne were piled high with the bodies of Wahine's victims, Mr Ellis said.

"When the first Bedford [truck] arrived it was apparent to us that there was a clear reluctance on the part of those present to attend to the bodies,'' Mr Ellis said.

"Nobody did anything, so we thought 'well, OK, someone's got to do something'.''

Mr Ellis' group stepped in, climbing on to the trucks, loading the bodies on to trolleys and wheeling them inside to be certified as deceased.

By midnight, they had cleared seven trucks and cared for 39 bodies, he said.

"You had to pull the bodies apart from other bodies on the truck.

"The smell was quite horrific. Some of them were bloated and some of them had been gashed on the rocks. Some of them you'd probably think nothing had occurred to them, they were just dead.''

BACK on the water, Mr Spiers was battling to avoid becoming one of them.

His covered inflatable life raft was carrying 13 or 14 passengers - a mix of the elderly and younger families with children - when a monstrous wave, up to 30 feet (9.1m) high, flipped the raft.

Mr Spiers was thrown clear, but then had to swim after the raft as wind and waves pushed it away.

"When I got to the raft there was an old lady, trapped outside. She was obviously drowned.''

The rest of the passengers were still inside the upturned raft, but Mr Spiers could hear some talking, trapped in an air pocket.

He did not have a knife to free them, but then, amid the waves, up popped the head of a man clutching a baby.

Mr Spiers pulled them both on board, placing the baby "in a puddle of water on the bottom of the raft''.

The other man then produced a knife, which they used to cut through the raft to free those inside.

"The first one I came across was a wee boy, about 2, 3, 4. He was drowned. Then another woman, and she was drowned.

"The rest just all sort of sat there looking at you.''

Unable to right the raft, Mr Spiers sat on top and contemplated his fate.

"I thought 'how the hell am I going to get out of this?'

"I was at the mercy of the elements. There was nothing I could do.''

MEANWHILE, Mr Stewart's lifeboat was also battling the storm.

A tug approached to attempt a rescue, but was picked up by a wave just as the lifeboat dropped into a trough below.

The two vessels crashed together, flipping the lifeboat and throwing Mr Stewart and the other passengers into the sea.

"There was people in life jackets everywhere, but the boat was upside down.''

For the next 30 minutes, Mr Stewart and the survivors tried to cling to the upturned lifeboat as breaking waves repeatedly swept them off.

"It had these ropes which you could cling on to, and I remember getting out of the water and kneeling on the lifeboat at one stage. Then you'd look up and there's this great big huge wave breaking over us.

"That was probably the only time I got scared . . . because each time you swam back there were less people than previously clinging to this upturned lifeboat.''

But chance was not done with the men.

For Mr Stewart, a sudden drop in the wind allowed a fishing boat to come alongside and pluck him and the other survivors to safety.

He was taken to Seatoun wharf, where volunteers offered blankets and hot coffee, and was later taken in by Clutha MP and then-Minister of Transport Peter Gordon.

Nearby, Mr Spiers was eyeing the approaching rocky coastline - which was to claim many victims that day - with trepidation.

"I thought 'this is it, we're going up on these rocks and God knows what will happen from there'.

"But this little old boat spotted us and they backed in and threw us a rope and dragged us out.''

He and the other survivors were rescued and dropped at Seatoun wharf. Mr Spiers was piggybacked to a waiting bus by a policeman and handed a cup of hot soup.

"I can remember shaking, trying to drink my soup, and the lady said 'do you want me to hold it for you?' I said 'no, I'll get it down me. Some of it might go down the front of me, but I'll get some of it in'.''

Mr Spiers lost sight of the baby he helped save in the confusion, but, by a twist of fate, heard years later she had survived.

He was volunteering on the Spirit of Adventure youth development tall ship in the 1980s when he shared his story of Wahine with those on board.

A young girl made a connection, telling him she went to school with a girl who once told a story of being a baby on Wahine, being trapped in an upturned liferaft, and being saved.

"She was fine,'' Mr Spiers said.

ANOTHER twist saw one of Mr Stewart's batting gloves - left behind on Wahine - find its way back to him in Dunedin.

The glove washed up on the Wellington coastline months after the disaster and was found by a woman who, spotting an Otago Sports Depot logo, posted it back to the store.

The store's manager recognised Mr Stewart's initials and returned it to him.

Mr Stewart keeps it tucked away in a drawer, where it remains a treasured memento.

"It just sort of reminds you how lucky I was, really.

"I'd probably never been fitter in my life. In the end that probably helped me survive that ordeal.''

TIMELINE OF A TRAGEDY

THE WAHINE DISASTER

• Lyttelton to Wellington ferry service carrying 734 passengers and crew.

• Caught in one of the worst storms on record on April 10, 1968.

• Collision between Cyclone Giselle and southerly front in Cook Strait generates winds of over 100 knots (185.2kmh).

• Wahine capsizes after striking Barrett Reef at entrance to Wellington Harbour.

• Passengers and crew abandon ship; 51 people die.

TIMELINE

April 9, 8.40pm:

Wahine leaves Lyttelton bound for Wellington.

April 10, 5.50am:

Captain Gordon Robertson decides to enter Wellington Harbour in winds over 50 knots (92.6kmh). Winds jump to over 100 knots (185.2kmh) as vessel reaches entrance.

6am:

Wahine’s radar fails; huge wave strikes ship, which is pushed towards Barrett Reef.

6.35am:

After trying repeatedly, and unsuccessfully, to turn into waves and head back out to sea, Captain orders full astern.

6.40am:

Wahine strikes Barrett Reef. Engines damaged, ship taking on water. Watertight doors closed, anchors dropped, but they drag as ship drifts further up the harbour. Weather makes it impossible for rescuers to reach the stricken ferry.

11am:

Tug reaches Wahine. Tries to secure a line to the ferry.

11.50am:

Line secured, attempt made to tow Wahine to safety, but line snaps. Further attempts to secure line fail.

1.15pm:

Wahine listing heavily to starboard. Order given to abandon ship shortly after.

2.30pm:

Wahine capsizes as survivors come ashore at Seatoun. More survivors blown across harbour to Eastbourne Beach, where many die on rocks of exposure.

• Source: ‘Timeline to tragedy’, URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/wahine-disaster/timeline, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 26-Aug-2014