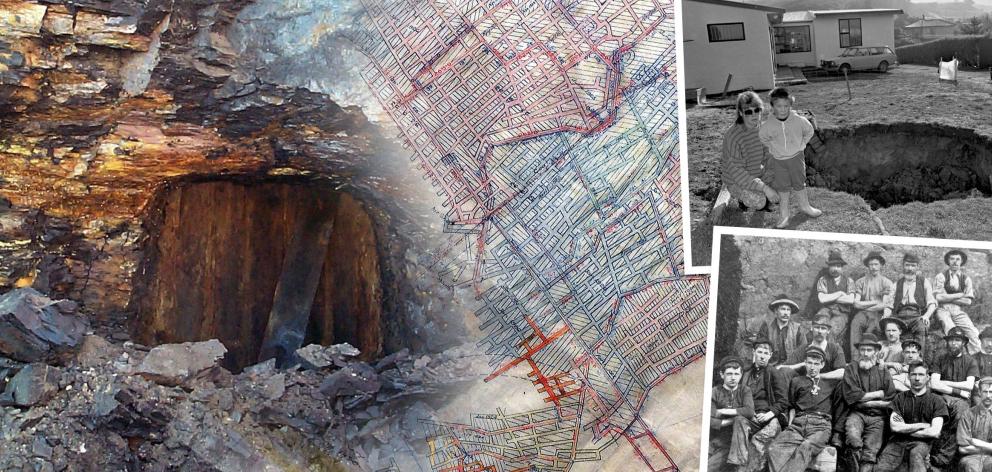

Three small openings - the largest just over 1m deep - hidden by long grass in the William Martin Reserve in Fairfield.

They emerged in October and, to the casual observer, probably seemed entirely unremarkable.

But authorities acted swiftly - contractors rushed to the site, peering gingerly into the openings while arranging orange cones and danger tape to keep the public away.

Engineering geologists soon followed and the openings were given a new name - sinkholes.

But it was what lay beneath, hidden in the darkness and by the passage of time, that was the real concern.

Down below lies the remains of an old coal mine, closed up and abandoned for more than a century.

Some of the tunnels stretched 80m below ground and were big enough to lead a horse and cart down, while others were so narrow, the miners had to crawl.

By 1903, when flooding forced its closure, more than three-quarters of a million tonnes had been extracted from the mine.

Eventually, its entrance was sealed using explosives, to keep children out, and knowledge of its existence began to fade.

But the network of tunnels remained, slowly degrading, filling with water and collapsing in places underneath the ground.

Years later, during construction of the Fairfield bypass of Dunedin’s southern motorway in 2000, a camera was lowered into one of the voids and captured images of a tunnel still in good condition.

When construction followed, the workers "crashed right through" the tunnels as they drove piles for the motorway deeper into bedrock, Andrew Holmes, an engineer who worked on the project, said.

The project unearthed other old mine tunnels and entrances as well, and a section of the new motorway was built like a bridge - designed to span the old mines below - in case they collapsed.

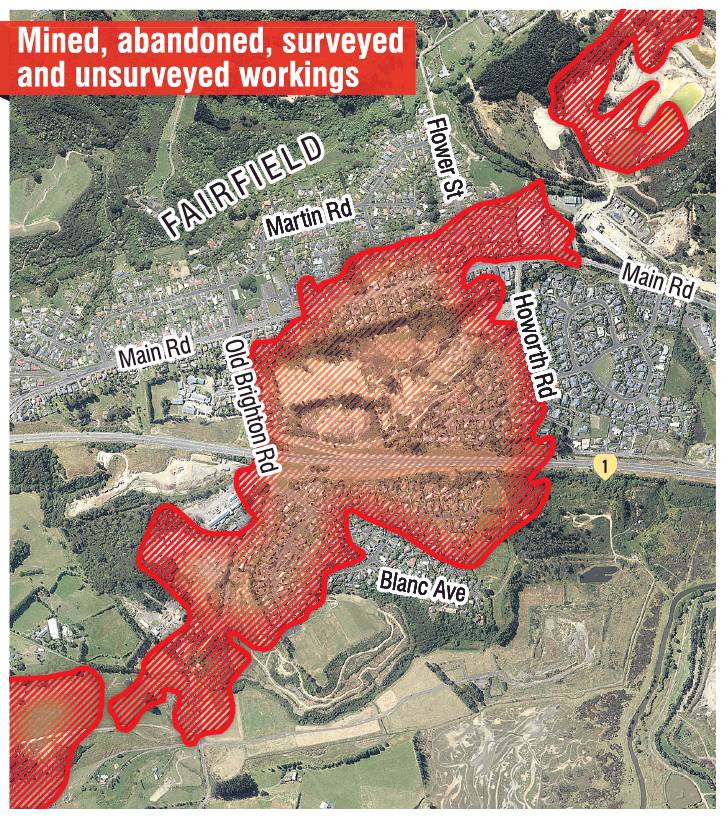

But they were far from the only mines in the area.

Across Green Island - and as far away as Brighton - the landscape is dotted with old coal mines and their tunnels, some of which connected to form wider networks.

The area was one large coalfield used to power Dunedin and, by 1939, more than 3.1 million tonnes of coal had been extracted.

Some of the workings extended more than 1km below ground, as workers followed the coal seam deeper and deeper.

While some had long since sagged, collapsed or been destroyed, others still offered fresh reminders of their presence.

Fairfield resident Graeme Duthie discovered a tunnel by accident a few years ago while driving his tractor up a sloping paddock at the back of his lifestyle block in Old Brighton Rd.

Mr Duthie told the Otago Daily Times a section of ground - already saturated by heavy rain - had collapsed under the weight of his tractor, opening a black void in the hillside.

"It collapsed into the mine - that revealed the coal mine underneath," he said.

The hole exposed part of an entrance tunnel, known as an "adit", which once began nearby and led deeper underground.

Mr Duthie said he would have "loved" to venture inside, but deemed it "too bloody dangerous", so he covered the hole and used it as an offal pit instead.

But it was not the only sign of mining found on his property, which still had mounds of old coal mine tailings - pieces of timber, concrete and iron still jutting from them - and the collapsed remains of a second mine entrance buried amid bushes.

His shed was also built on the foundations of an old railway line, which once led into the mine.

And, looking out across neighbouring paddocks, Mr Duthie pointed out other slumps in the landscape.

"Ever since I came out here, there’s been all these hollows in the paddocks. That’s the coal mines.

"It’s just riddled with coal mines underneath. Absolutely riddled with them. All those houses over there [in Fairfield] are just sitting on bloody stilts really."

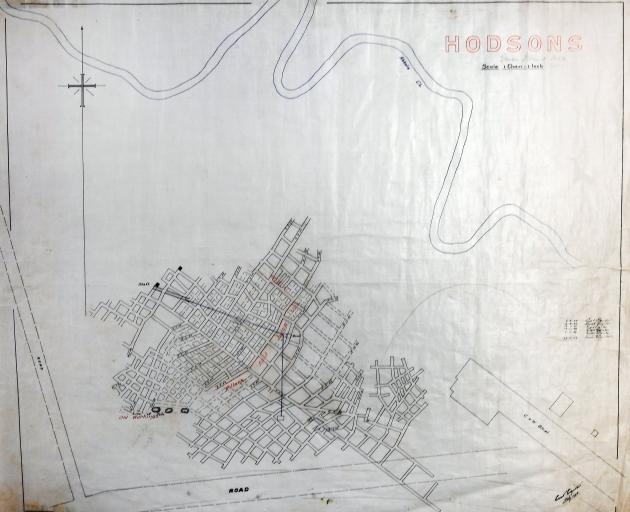

There, old maps in large tubes cover entire tables when rolled flat, and detail networks of tunnels with names such as Christies, Hodsons, Barclays, Jubilee and Abbotsford.

However, the search also highlighted one of the problems with old mining records - they are incomplete, concealing the true number of mines, their exact locations and the extent of diggings.

The Dunedin City Council has already identified historical mine workings as a hazard for a large swathe of Fairfield and surrounding areas, including part of Old Brighton Rd and Ocean View.

However, those controls were only useful to the extent mining activity was known, DCC building services manager Neil McLeod said.

"We know the whole area has got the potential to be mined, but I’m not sure that we actually know precisely where every mine is," he said.

Building controls had been in place since the formation of the modern DCC in 1989, but many houses in Fairfield predated that period, he said.

Records, some of them dating back decades, also acknowledged some houses had been built over old mines, including in Fairfield.

The risks were highlighted in Ocean View in 1989, when a small earthquake on July 12 opened up a large hole in the back garden of a home at 6 John St.

The hole revealed a long-forgotten coal mine, with tunnels extending in all directions, putting 14 homes in John St and Brighton Rd at risk.

The mine - known as the Brighton or Walker No 1 Coal Mine - operated from 1887 to 1893, and was one of several in the area, but had been overlooked when the land was subdivided in the 1920s and built on from the 1940s.

But, as the threat to people and property values became clear, debate erupted over who was responsible.

The Silverpeaks County Council, the DCC and the Crown all initially rejected liability, as increasingly stressed and angry homeowners demanded action and accusations of negligence flew.

A consultant geologist, Barry Douglas, was called in to study the situation, and warned further collapses were "very probable" but their timing and frequency were "uncertain", and Civil Defence expressed "concern".

Eventually, the Crown agreed to buy at-risk homes, which were removed and the area turned into a reserve - but work did not stop there.

It identified large areas as potentially at risk, to differing degrees, and warned mine-related subsidence could occur up to 100 years, or more, after mining ceased.

There was already evidence of subsidence across the area, including circular depressions, gullies, holes and "hummocky ground", and records from 1905 indicated subsidence was "commonplace" in some areas.

One incident had undermined a section of railway line, while another cavity had swallowed part of a below-ground petrol tank in Fairfield.

There was also evidence of crown holes - one of them 40m wide and 10m deep - to the west and southeast of Bremner St.

When the Bremner St subdivision was being developed, a bulldozer had also "dropped into a void", and there were "numerous" other crown holes visible in aerial photographs of the wider area.

The possibility of future subsidence in Fairfield was also considered "likely", despite a lack of recent activity, and the report warned crown holes could occur "suddenly ... with little or no warning".

However, it also noted the lack of accurate information as a problem.

While major mines were generally mapped, areas mined prior to the 1870s either were not or the records had been lost.

And maps that did exist "may not show the full extent of actual mining", it said.

Mining was not always recorded during periods of high activity, including during both world wars.

And nor were all areas in which mine pillars - the supporting walls of coal left below ground - had been removed during later stages of mining.

The accuracy of records was therefore "often highly questionable" and "represents only a best guess", it said.

The condition of abandoned tunnels was now also "generally unknown", it said, but stability could be affected by other factors, including earthquakes.

Seismic events risked triggering the collapse of "marginally" stable old mines, it warned.

"Surface subsidence may be triggered by future earthquakes or other processes."

When subsidence did occur, it came in the form of crown holes or broader troughs, and shallower areas of mine workings - such as the tops of vertical shafts or entrance tunnels - were "by far the biggest risk".

An attempt to address the limited knowledge of abandoned mines has been made by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, together with WorkSafe, triggered by the Pike River disaster.

That included scouring the country for old mine plans and other information - held in collections such as those of Archives NZ and the Hocken Library in Dunedin - and publishing it on the NZ Mine Plans online database.

Mr McLeod told the ODT the old mines were "most definitely" on the DCC’s radar, although there was also no regular, ongoing monitoring of their condition.

An exception was the William Martin Reserve which, following the emergence of new sinkholes, would be monitored for further signs of subsidence.

Back at his property in Old Brighton Rd, Mr Duthie said his own investigations into the area’s mining history provided a cautionary tale.

"A lot of people would be surprised if they actually knew what it was like underneath them."

Advertisement