Mary Williams digs into the science and discovers why the area is so vulnerable to climate change.

Wising up to the water

Wising up to the water

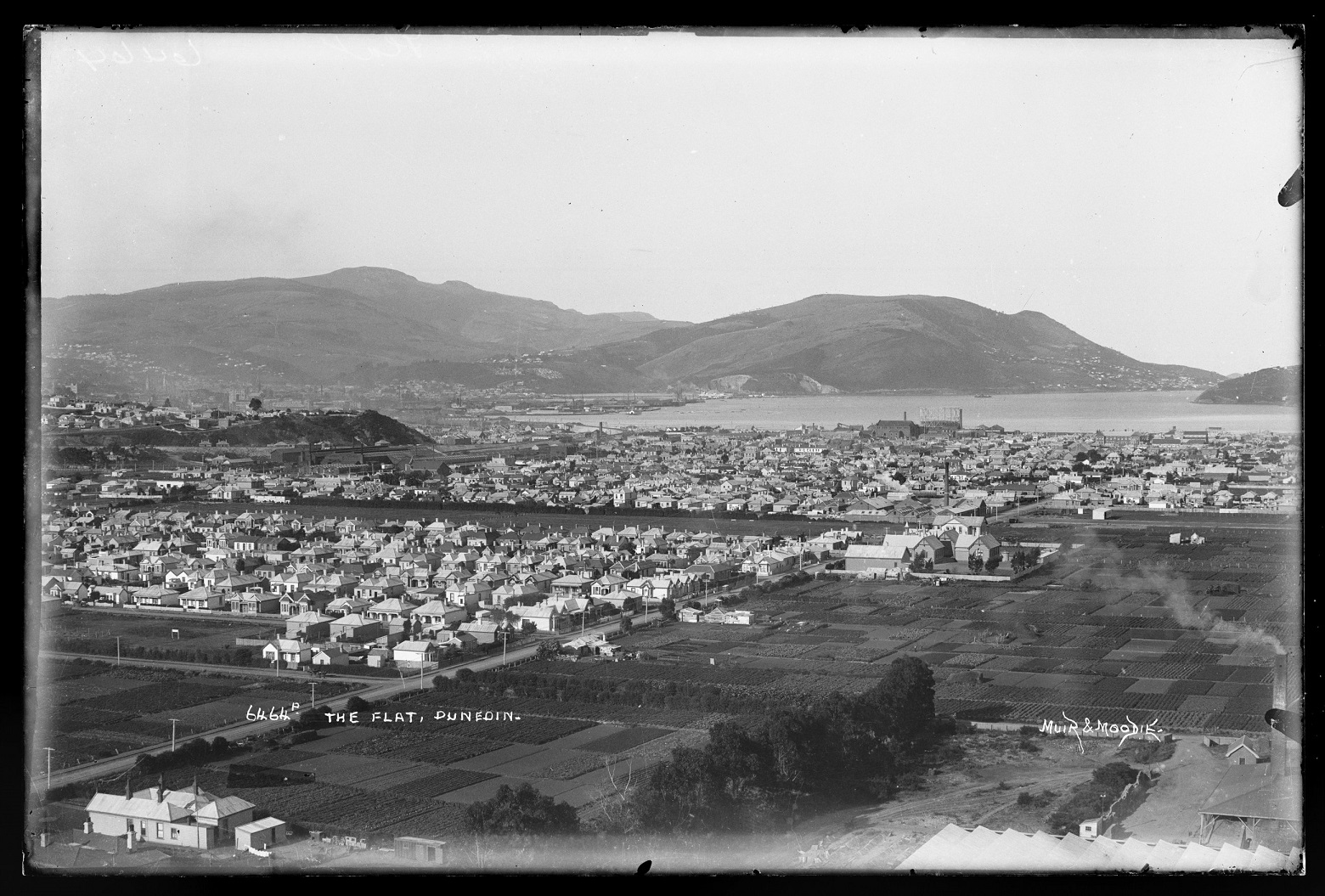

Back in the sea mists of time, when the oceans were lower, the 6sq km of South Dunedin was a muddy river estuary. Then it became a tidal flat with a large salt marsh at the northerly harbour edge. Towards the south, there were freshwater marshes, a lagoon and some dunes where the land met the mighty Pacific Ocean. It was, in short, wet.

To the east and west were hills that are still there, edged by ancient sea cliffs and terraces proclaiming the area’s watery past.

Below them, a proud community sits very close to sea level, with schools, shops, cafes and about 3000 homes. More than 60% of the ground is covered in streets or buildings.

The northerly coastline is now a strip of reclaimed land, 2m-3m high and topped by warehouses and megastores. The southerly coastline is a bank of 10m-high dunes.

Below the buildings, streets and remaining green spaces, often within arm’s length, is an underground water table, where the earth is saturated with mostly fresh groundwater.

In some places it is as close as 20cm from the surface.

A report released this month from GNS Science says that although the harbourside land reclamation provided "some degree of protection from coastal inundation" it also "caused the unfortunate and compromising effect of removing pathways for natural drainage".

South Dunedin sits at the bottom of a flat, mud-lined sink — with a natural plug hole largely clogged by the land reclamation, buildings, streets and its high water table.

Why does South Dunedin flood?

The remaining green space in South Dunedin is the only natural drainage pathway remaining. Rain seeps into ground that has limited water storage space above the water table. From there, it joins the groundwater and slowly drains away to the ocean, with the gentle help of gravity.

The emphasis is on the word slowly. Rain that falls in bucket-loads quickly can cause the groundwater level to rise sharply — by between 20cm and 1m — and flooding.

Flood prevention is therefore inevitably reliant on most rainwater being channelled efficiently to the sea by drains and pipes that lead to a pumping station, which filters out leaves and rubbish and discharges the water into the northerly harbour.

Everyone in South Dunedin understands this did not happen during the rainstorm of June 2015, which impacted about 1000 homes, causing economic and social damage estimated at $138 million.

GNS Science’s principal scientist Dr Simon Cox recommends South Dunedin people "adopt a drain" and keep it cleared of leaves and rubbish. The pumping station got a new filter after the flood.

These basics, important as they are, will not stop a worsening water problem due to climate change.

Climate change bringing more water

Climate change means that in the worst rainstorms, the intensity — millimetres falling per hour — will likely increase. Plus, the sea level is rising.

It is a double whammy. There is more rainwater arriving faster and struggling to get out, and more saltwater trying to get in.

Dr Cox says there is a need to plan to manage "water coming from above, below and sideways".

"Above" means intense rainstorms.

"Below" refers to the water table rising progressively higher, permanently.

In 10 years’ time, the water table will on average have risen by about 3cm-4cm, Dr Cox says. It will keep rising after that.

As well as causing more saturated ground, springs will pop up, technically referred to as emergent groundwater.

Saturated ground and emergence will not happen at the same time everywhere. The water table is typically closer to the surface near the hills and lower near the sea, but varies. Groundwater will emerge earliest where the water table is already close to the surface, there is a dip in the land, and sandier earth.

There are two reasons the water table is rising.

As the sea level rises, it is harder for rain to seep through the groundwater and out to the ocean, because the power of gravity diminishes.

Meanwhile, seawater is increasingly forcing its way in — through the side of South Dunedin’s ground — to join the fresh groundwater.

This "provides a little more time for the city to plan," Dr Cox says.

Initially, emergent groundwater could be just "small nuisance seeps" during the highest tides or rainstorms, but eventually the flows will become permanent.

"The area of unsaturated ground gets smaller and smaller and then there is nowhere for the water to go other than run off the surface."

In the meantime, there are other problems that rising water brings, aside from flooding. Damp homes can cause respiratory illness. Roads and building foundations can be damaged. There can also be vulnerability to liquefaction — when the ground turns to sludge in an earthquake and buildings sink and break.

When and where will it happen?

People want to know when the water will be unavoidably present and require more action than clearing a drain.

The GNS report, and other ongoing collaborative work involving scientists at the University of Otago and elsewhere, helps inform the timeline and planning decisions.

GNS modelling shows that already, in an intense rainstorm of 6cm or more in 12 hours, and when tides are highest, there is a loss of capacity within the ground to store rain in some areas, and in some places emergence is modelled to happen. In the 2015 flood, more than 14cm fell in 24 hours in the Musselburgh area.

One area is part of Forbury Park, unsurprisingly bought by the Dunedin City Council this year, and some streets running inland behind it. Another area centres around Marlow St in Musselburgh and some neighbouring streets. Smaller areas are marked in pockets around Macandrew and Hillside Rds.

By about 2080, the sea could have risen by as much as 40cm compared with today. GNS forecasts this would mean "widespread emergence of groundwater as springs across South Dunedin during prolonged periods of rain or rare storm surge events".

By 2090, the sea could be half a metre higher than today and water flowing permanently out the ground in springs.

It could take about 60 years longer to reach that point. Timing is dependent on global emissions of greenhouse gases. If we do not curb them quickly, the sea could continue to rise fast — by about 5m over the next 300 years, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Regardless of timing, it is a fact the sea is already rising. As well as saturated ground and emergence, South Dunedin will suffer increasing inundation from high tides at the harbour side this century, unless coastal protection is improved. Erosion of dunes at the southerly edge, exacerbated by the rising ocean, is also a concern.

Planning for the future

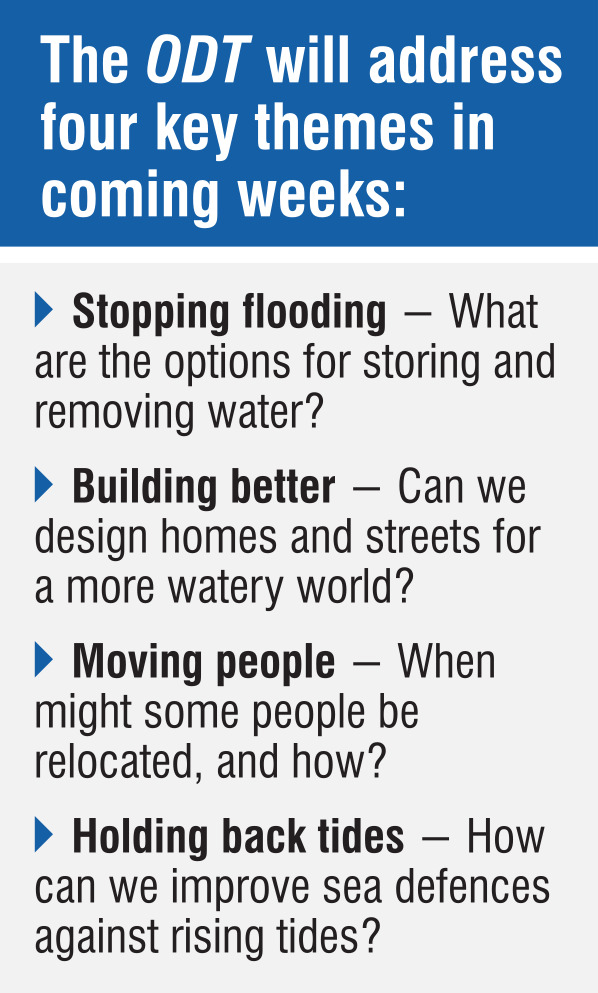

The Otago Regional Council — which partnered with GNS to produce its research — and the DCC are a united front conveying two messages: we know South Dunedin has a more watery future; let’s plan. The councils are working with the community to produce a South Dunedin Future adaptation plan by 2026.

A "long list" of 16 potential approaches has been compiled, ranging from better drainage, to restrictive building design, to relocation of people away from vulnerable places. A five-week public consultation is under way and it is not about picking one approach. Many will be needed.

The city council is consulting on a separate 2024-2054 Future Development Strategy for the whole city — the draft document says there is a hope of "no net loss of residential development in South Dunedin".

Loved as it is by residents, South Dunedin is not Amsterdam, built on centuries of wealth and home to about a million people. South Dunedin is small, 7.4 out of 10 on the deprivation scale, with many older homes and a diverse community. It has beautiful beaches and bracing sea air, but needs to know its future.