In the 1920s this factory building was a hive of activity, all thanks to a humble invention. The Star reporter Simon Henderson explores the all but forgotten history of inventor John Eustace.

Marjorie Jarvis (nee Eustace) hasn’t always been fond of her maiden name.

As a pupil, her surname prompted cries of "Useless Eustace" - perhaps because of Jack Greenall’s newspaper cartoon strip of the same name about a hapless duffer.

But she is proud of her grandfather John Eustace and his anything but useless invention.

He developed a flanged, airtight lid in 1884, still recognisable on paint tins or golden syrup tins today.

Speaking to the Otago Daily Times in 1927, Mr Eustace described how the idea came about.

At the time a tin lid went over the outside of the collar or lip of a tin can.

"I conceived the idea of reversing the collar, so that the lid sank down a little way inside the tin, not outside it."

This was potentially an idea to make him a multi-millionaire.

Mr Eustace approached Robert Smith, of the paint firm that became Smith & Smith, who helped Mr Eustace make a patent application for "an invention for hermetically closing tin boxes with the lid without soldering".

"We had not the faintest idea of its possibilities," Mr Eustace said.

He sent off specifications to England for dies to make the tins, and about four month after the dies arrived from England , he noticed tins of paint were coming from Manchester with lids exactly the same as his invention.

He realised English firms had seen a patent had been taken out in New Zealand but not worldwide, and had "pounced" on the idea, making it too late for Mr Eustace to take advantage of what he had.

The English had essentially "pirated" Mr Eustace's invention, although without a worldwide patent it was legal for them to do so.

Mr Eustace was sanguine about missing out on millions.

"It would have been worth no end of money ... however it is no use howling about it."

Undeterred, Mr Eustace continued to create tins for the local market and even submitted a second patent in 1896 for an improved airtight cover.

Mr Eustace set up a company in 1896, working out of premises in Moray Pl.

"In the first year we made about five tonnes of canisters."

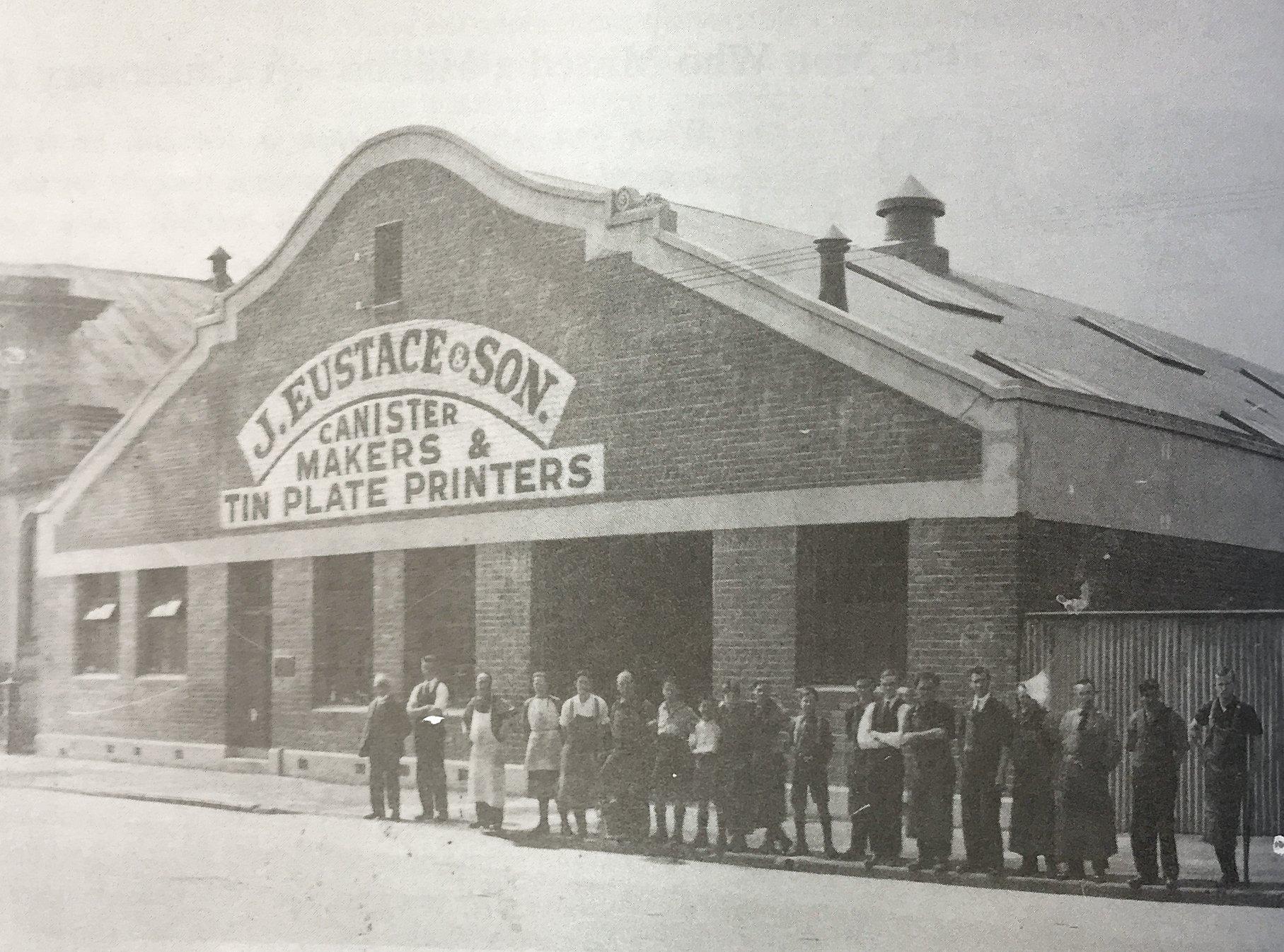

The South African war (also known as the Second Boer War) provided the firm with contracts for large quantities of meat and jam tins. In 1923 the company secured a quarter-acre site in Great King St where a large 12,000 square feet (1115sq metre) factory was built.

John Eustace had two daughters and one son, Mrs Jarvis’s father — John Williams Eustace.

Mrs Jarvis said her grandfather always used to say to her father, ‘you are going to be taking this over when I leave the world’.

"My father would say ‘Well I want to be a doctor’."

But that wasn’t to be, and when John Eustace died in 1944 aged 89, despite initial hesitation, his son John Williams Eustace ran the business until he retired, when it was sold to J. Gadsen & Co.

While her father might have been reluctant to run a business, Mrs Jarvis ran her own company for many years.

"It was called Robertson’s Ladies Wear."

From her store by the exchange she sold clothing, haberdashery items and nylons.

The nearby "Chief Post Office girls" were regular customers, she said.

Now 91 years old, Mrs Jarvis wanted to share the history of her pioneering grandfather.

"I thought someone would be interested before I leave the world."