Victims of historic abuse in state care are fighting back, demanding justice - in cash and apologies - to help rebuild broken lives. But some are going further.

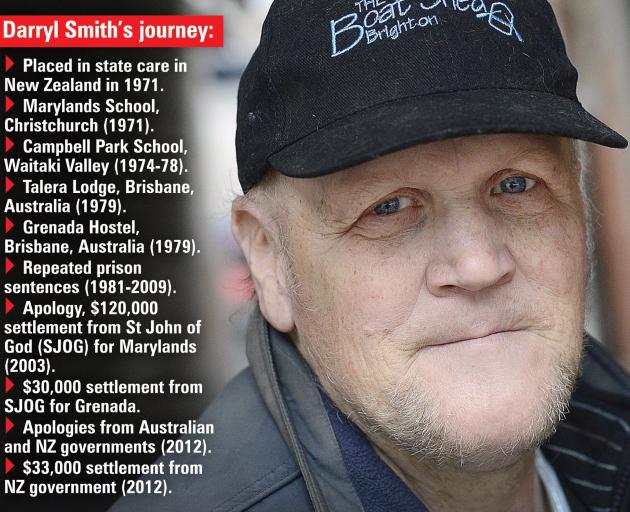

In the second part of ODT Insight’s special investigation, Chris Morris tells Darryl Smith’s story.

The Dunedin man spent more than a decade in state care, in New Zealand and Australia, beginning as a 7-year-old boy in the early 1970s.

It was an experience that exposed him to sexual predators at one institution after another, including two run by the same Catholic order - the Brothers Hospitallers of St John of God.

And, despite receiving payouts and apologies on both sides of the Tasman, Mr Smith says it is not enough.

The 53-year-old wants justice in the form of a national inquiry and public apology from the New Zealand Government.

But he wants something more from the Church.

''I'm out to destroy them,'' Mr Smith told ODT Insight.

''They caused it all. It's their fault. If it wasn't for them in the first place, I wouldn't have gone down this road.''

It is an anger that has been bubbling inside Mr Smith for more than 40 years, as childhood abuse led to adult criminal offending and, eventually, prison.

He still sleeps with the lights on, decades later, to keep the nightmares at bay. But, even today, an innocuous comment is enough to trigger a flashback.

''Some of them them are quite horrific. Some days are better than others. Some days I can go with no nightmares at all.

''We [victims] are marked for the rest of our lives. To this day I still sit in the bath and I scrub myself raw, because of what happened.''

- Part 1: Delivered into the predators' hands

- Saint John of God response

- Roxburgh Health Camp

- Catholic Church

It is a mark Mr Smith has carried since he was first targeted by an abusive brother from St John of God as a child in 1971.

He could not see it in the mirror, but it was clearly visible to the predators who preyed on the already vulnerable.

And every time he walked into a new state home, in Otago or elsewhere, the predators would turn their heads to look.

''I would put it like a pride of lions attacking young deer.

''Every time a little kid came in, you could see the lions and their faces starting to look with interest.

''The first night there, you get blanketed, beaten up and raped by the older boys.''

It was a childhood of torment that began as a 6-year-old with a mild intellectual disability, when he started running away from home.

Mr Smith put it down to a childhood ''phase'', but his parents were ''struggling to cope''.

Eventually, when a Department of Education staff member suggested he go to Marylands School in Christchurch, they agreed.

The live-in facility catered for boys with intellectual and physical disabilities and behavioural problems, and his parents thought they were doing the right thing.

But their decision condemned him to life in what has become a notorious centre of historic sexual abuse, run by St John of God.

''I still remember playing on the floor with toys while my parents talked to this person from the department.

''I went in all right, but I came out completely different.''

The school's problems hit the headlines decades later, when the first of 125 complaints alleging historic sexual abuse began to emerge.

The Catholic order eventually paid out $5.1 million to victims, and two of its brothers were convicted on historic sexual abuse charges after a police investigation.

Mr Smith said he was among Moloney's victims, but he was also targeted by other brothers and older boys at the school.

Mr Smith was moved from Marylands after nine months, first to Christchurch's Templeton Centre hospital and later to a series of State care institutions across New Zealand.

That eventually led to Campbell Park School, in the Waitaki Valley, beginning in 1974, where violence and sexual abuse by staff and older boys against younger boys was ''rife'', he said.

One of those to target Mr Smith was Peter Holdem, then one of the school's older boys but later, in 1986, to earn notoriety as the convicted killer of 6-year-old Louisa Damodran.

''Everywhere I went, it was all the same stuff, just a different day. Everywhere I went in life I was getting hurt,'' Mr Smith said.

In 1979, aged 15, he joined his family in Australia, but was soon declared a state ward of Queensland.

He ended up in Talera Lodge, then run by the Queensland Baptists, where he was abused by a female staff member and raped by an older boy, he said.

A police investigation last year failed to identify the older boy and found the female staff member had died a decade earlier.

Later in 1979, Mr Smith was moved again, to Grenada Hostel in Brisbane, and found himself back in the care of St John of God.

More abuse followed, this time at the hands of Brother Bede Donnellan, he said.

''If I had known that ... I would never have gone there.''

Donnellan - whose real name was John Donnellan - died in 1995, before facing justice, but the Church's Professional Standards Office in 2008 concluded ''on the balance of probabilities'' Donnellan had sexually assaulted Mr Smith.

But by then Mr Smith's childhood had led to a life of crime, and he was imprisoned repeatedly for theft and fraud offences between 1981 and 2009.

His experiences also drove a wedge between Mr Smith and his parents, who had refused to believe his claims of abuse as a child.

''When I told my parents 'this man touched me' ... I got a hiding.''

Their estrangement continued until 2002, when his parents saw a television documentary detailing the abuses at Marylands.

Soon after, Mr Smith received a letter from his parents while in jail.

''It said 'We finally believe you, Darryl'.''

It was the start of a new life for Mr Smith, who vowed to stay out of prison and focus on seeking help and justice.

The following year, he received an apology and $120,000 in compensation from St John of God for his experiences at Marylands.

Six years later, after fighting St John of God over a second payout for his experiences in its care in Australia, the Catholic order relented and paid him a further $30,000.

In 2012, he also received apologies from the Australian and New Zealand Governments, and a $33,000 payment after speaking to New Zealand's Confidential Listening and Assistance Service.

He also participated in Australia's royal commission into child abuse, which offered ''a wee bit of closure''.

But that was still not enough for a childhood destroyed, Mr Smith said.

''It's destroyed me emotionally. It's given me a criminal record I didn't want. I've been robbed of everything.''

As a result, Mr Smith remained a thorn in the church's side - emailing regularly and seeking additional settlements through an Australian lawyer, Peter Karp.

Mr Smith said payments to date were ''blood money'' and the sums involved ''a total joke''.

A law change in Australia last year allowed abuse victims forced into unfair settlements to seek fresh payments, and Mr Smith planned to keep fighting.

He has also launched a series of petitions in New Zealand, including one calling on St John of God to pay for a lifetime of counselling and healthcare for all victims of Marylands.

He also wanted victims' criminal records wiped, and for the New Zealand Government to commit to a royal commission.

In the meantime, he has started a victim support group and is considering launching a political party to promote victims' rights.

But perhaps most audaciously, he is seeking fresh financial settlements for headline-grabbing amounts - including $5 million from SJOG and $1 billion from the Catholic Church itself - and has filed a complaint against SJOG with the International Criminal Court.

He has even written to the Vatican, asking to meet the Pope.

The only response to date has been from SJOG, which offered Mr Smith another 10 counselling sessions, free of charge.

The gesture, like anything SJOG could offer, was not enough for Mr Smith.

''To me, reimbursing me is giving me my life back, and they can't give me my life back, can they?''

Thankfully, Mr Smith has also found another outlet for his emotions - painting.

''Before I started art, I had like a black cloud around me. It's still there. I can get thunderstorms quite quickly ... but it's got blue sky there at the moment, just like outside.''

Lifeline: 0800 543-354

Depression Helpline (8am-midnight): 0800 111-757

Healthline: 0800 611-116

Samaritans: 0800 211-211

Suicide Crisis Helpline: 0508 828-865

Youthline: 0800 376-633, free text 234 or email talk@youthline.co.nz

Rural Support Trust: 0800 787-254