A story in Thursday’s Otago Daily Times offered a snapshot of the immensity of the challenge which faces southern mental health services.

A distraught Southland woman revealed she had called for emergency help after having suicidal thoughts and that two months later she was still waiting for a call back.

Her story is the tip of an iceberg of often hidden distress in the community. The Southland Mental Health Emergency Team alone receives between 600 and 800 calls a month, a disturbing number, even allowing for the fact that some of those will be multiple calls from the same person.

This is a national, as well as a regional issue, and in 2018 the Government set up an inquiry into mental health and addiction, a wide-ranging investigation which attracted full houses for its consultation sessions in Otago and Southland.

The government response to the report promised great things, many of which are still being addressed.

The Southern District Health Board, well aware its services and facilities faced many issues, last year decided to carry out its own mental health and addiction services review.

Earlier this month, the 136-page report was released, and the board promised to action its 35 recommendations.

That may be easier said than done.

For example, the report’s authors pulled no punches on the partly dilapidated facilities at Wakari Hospital and called for the board to signal its eventual closure but the services at the Dunedin hospital will need to be relocated elsewhere, and the SDHB will need to convince a government which has already provided $1.47 billion for a new hospital that it also needs several million more to rebuild mental health facilities.

The report also calls for greater resourcing of mental health services, especially staffing. But, like almost every other part of the health system, there is a shortage of locally trained professionals, as well as Covid-19 related barriers to bringing in specialists from overseas.

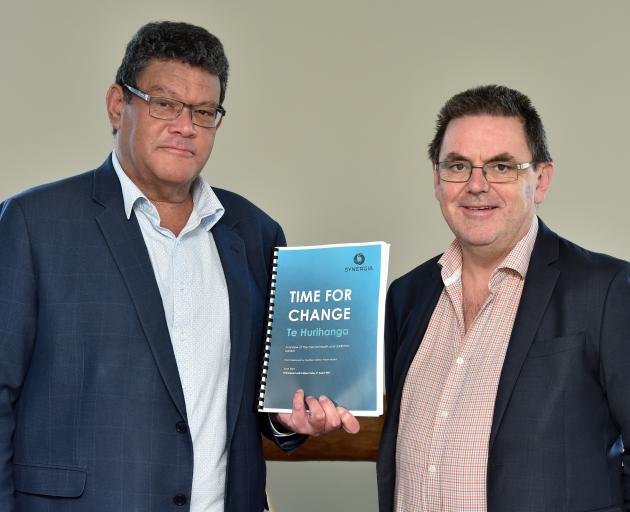

Despite these barriers, SDHB chief executive Chris Fleming is confident real and meaningful change will ensue from a report pointedly titled "Time For Change".

"The title is not accidental. We are committed to change and this is the time to do it," he said.

"The board have committed to driving change over the next 12 months."

In less than a year, the Government’s health system restructuring will mean DHBs are no more, but Mr Fleming said the issues raised in Time For Change were too large to be lost in the mix.

With 610 full-time equivalent SDHB staff in the sector, an operating budget of more than $167million, 26 community-based providers and a range of non-government organisations working in the field, mental health and addiction is no small part of the southern health system.

"This report identifies huge gaps in the continuum of care and we have to do something about it ... this won’t be the whole solution but it is a critical part of the pathway towards ensuring people right across our district get access to timely and appropriate services," Mr Fleming said.

Putting clinicians and services in the right place is always an issue for the far-flung SDHB, the country’s largest health board by area.

In Dunedin there is about one mental health staff member for 416 people, but in Waitaki there is one per 1881 people and in Queenstown Lakes one per 2249 people.

"Workforce supply is particularly difficult at the moment, with the situation at the borders, but we will get through that," Mr Fleming said.

"But we need to recognise that that there are already some incredibly capable people working in the sector in our district and we need to ask, ‘how are we supporting them and how do we supplement them?’."

SDHB acting mental health, addictions and intellectual disability lead executive Gilbert Taurua is in the driving seat for implementation of the review recommendations, both in the wider sector and also more specifically in his Maori health role, for fulfilling the report’s ambition that at least 6% of the mental health and addiction services budget be available for Maori clients.

"There has been a significant underinvestment in the sector for some time and the board has recognised and there has been some additional funding in that area.

"The report does highlight the need to improve our addiction services because sometimes the outcome of underinvestment there can be seen in our inpatient services, so I think we need to build capacity in the community," Mr Taurua said.

Corinda Taylor, founder of suicide prevention charity Life Matters, was concerned that many families were unable to contribute to the review, and she hoped they would be included in any revamp of youth services.

"What strikes me is that the report identified that infants, children and youth in the 0-24 years age bracket comprise 31% of the total population of the southern district but attracted less than 15% of the total budget on mental health and addiction services in the 2020-21 financial year, yet when it comes to what needs to happen this report does not go far enough to specify how this should be rectified.

"They need to invest more heavily in this age group to prevent long-term issues and to take the opportunity to turn things around at a younger age by being more proactive," she said.

Kerry Hand, director of independent mental health provider Miramare, felt the review was thorough but that it had also traversed issues which were already well known.

"We’ve been here before ... six years on from the last review, Raise Hope, it’s hard to see any significant implementation and some concrete plans which were developed simply disappeared.

"Resources are lavish but simply in the wrong places, and shifting anything brings hell upon the heads of the managers, often stopping progress."

The review authors have already acknowledged Mr Hand’s concerns.

"We do not want this report to become a paperweight or door stop, to sit on a shelf gathering dust," they said.

"We want it to be used, to be read, to get dog-eared and to get added to, to be improved. It also represents a point in time that should be built on, completed and put to one side when done."

Advertisement