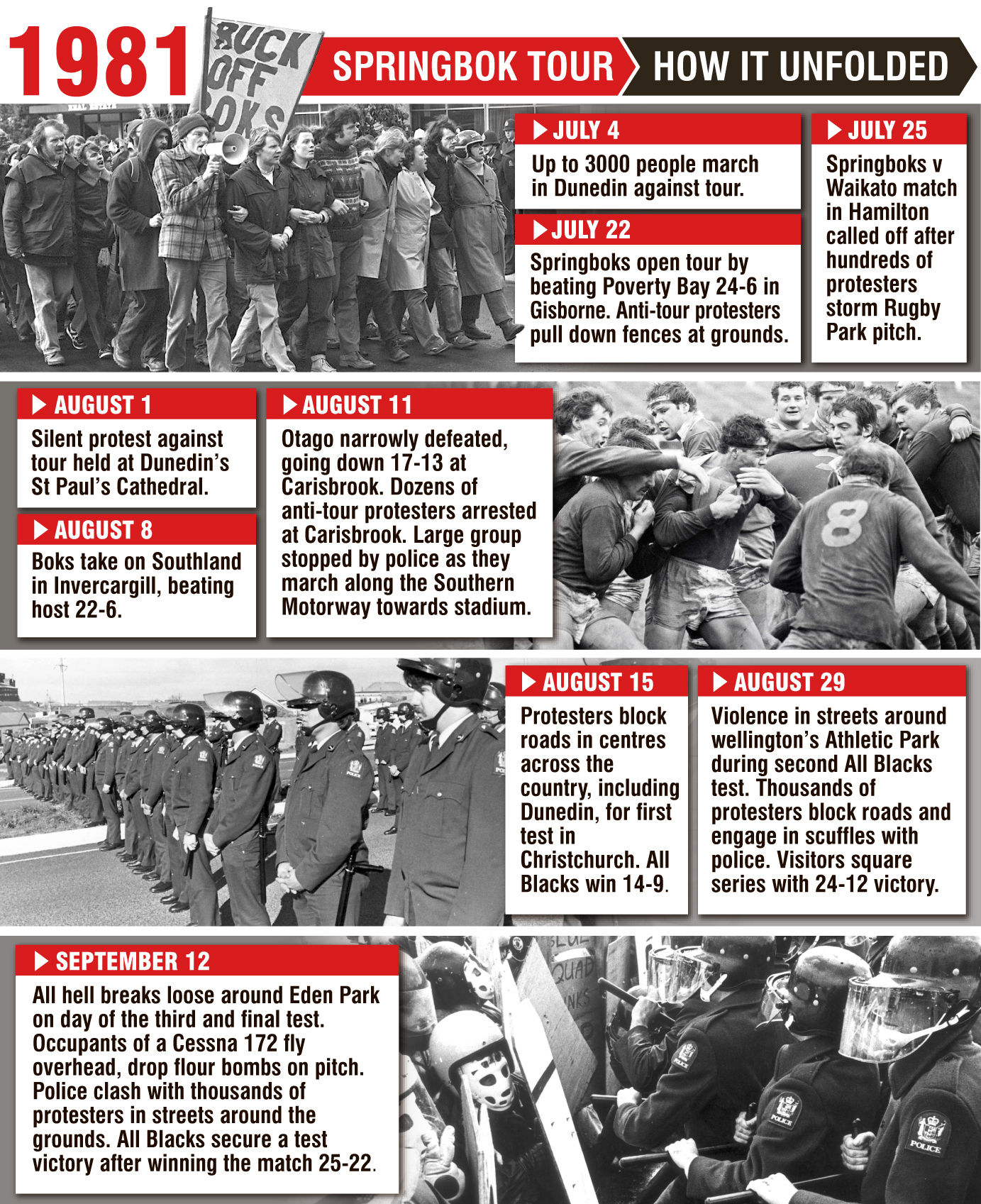

It was the tour that divided the nation, leaving a scar on the collective memories of people across the length and breadth of New Zealand. Four decades on, Daisy Hudson examines the events of the 1981 Springboks tour in the South, through the eyes of those right at the heart of the action.

It came to a head on the motorway.

More than a thousand marchers on one side, strong in their beliefs and strong in their language.

They were young and old, male and female, experienced protesters and first-time marchers.

On the other side was the thin blue line, police officers handpicked to stop an emotional powder keg from igniting.

There was anger as the two groups collided, and cries of "traitor" hurled at the officers. Later a protester would be attacked by rugby fans horrified at her views.

At nearby Carisbrook a different conflict was playing out, this time between 30 men on the paddock.

They were unfamiliar scenes in Dunedin, but then, the 1981 Springboks tour upended a lot of things.

Tough gig

Allan Grindell was a 23-year-old constable in Dunedin in 1981.

He loved his footy, played for Kaikorai, and didn’t really get what all the fuss was about.

He was of the view, as many were, that politics and sport shouldn’t mix.

So when he was picked for the Blue Squad, a team of police working on the controversial Springbok tour of New Zealand that year, he was chuffed.

Blue Squad was a group of 54 officers from Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin who would travel with the Springboks, getting them safely to and from games, hotels, and events along the way.

It was an important job. Anti-tour sentiment had been building for months.

The divisions were political, racial, town against country.

Protests attracted thousands of marchers around the country, who in turn were angrily confronted by pro-tour advocates.

Const Grindell had been part of Dunedin’s team policing squad, which was trained to deal with crowd control and mass disorder incidents.

But this would be a step up.

"We were all very excited about it, at that stage," the now 63-year-old said.

"None of us envisaged what was to follow. We knew there would be some reasonably heavy demonstrations, but I don’t think any of the guys that I worked with really envisaged what was going to happen."

That started to become clear when the Hamilton match was called off on July 25 over security fears.

He recalls being booed at the City Hotel pub in Moray Pl that night, because it was the Police Commissioner who had nixed the game.

His first taste of the South on tour was Invercargill, where the Boks played Southland on August 8.

The visit was uneventful, other than the hosts going down 22-6. So uneventful, in fact, that the team decided to stay in the city for several nights longer than they had planned.

"Invercargill was seen as very pro-rugby. They decided it was a safe venue," Mr Grindell said.

"I think we had a good time. We took them round to practices and did a few things like that."

A few days later, in Dunedin, it was a different story.

Tough choices

The Springboks were to play Otago at Carisbrook on August 12.

A few days before, 21-year-old Mark Hudson had just returned from a ski trip when fellow university students started congratulating him.

It turned out he had been selected for Otago for the coming match, called in after Gary Seear withdrew from the game for moral reasons.

His parents were stridently against the tour, and took part in marches.

His mother would also later serve as deputy mayor for Waitemata, alongside anti-tour protester and current Invercargill Mayor Sir Tim Shadbolt.

Nevertheless, she was pleased he had been selected and told him "do what you want to do". "It was the first time I realised ‘jeez, I’m in a situation now. I could make a choice’."

He made the call to play, and the next few days were a whirl wind.

"Everything happened so fast, politically, I didn’t have time to think about things."

The gravity of the situation didn’t sink in until the team was being shepherded into Caris brook on game day.

He still remembers the atmosphere in the changing room as the players prepared to run out, and their dedication to the team.

"If you were going to go through anything in life where you needed help, I look back and think ‘God, those 14 players, I’d want behind me.

"They were going to take on anything that was thrown at them."

The game went by in a bit of a blur. In a cruel twist, Mr Hud son broke his finger in four places in the first 10 minutes of the match. He played out the rest of the game, but did not play again for the rest of the season.

He initially returned to the Maori Club after the match. The club didn’t put pressure on him to stay or leave, but deciding he did not want to put the players in an awkward situation, he stopped attending.

Standing up, speaking out

Earlier, while police were escorting players safely to the House of Pain, about 1200 anti- tour protesters were beginning to march along the Southern Motorway overlooking the stadium.

Among them was Francesca Holloway, a 24-year-old Dunedin Hart official.

Growing up in a family with a focus on social justice, she had been involved in political movements and social causes since the age of 16.

She moved from Hamilton to Dunedin for a teaching job in 1978, and became involved in a fledgling anti-apartheid group.

By 1981 she was a fulltime organiser.

"When the tour came to Dunedin there was a feeling that people in Dunedin wanted to make their feelings known and wanted to stand up and be counted.

"At the same time there was a lot of fear, because it had become very confrontational," she said.

"I will always remember one couple who said they would love to be participating but they were going through adopting a child and they were so afraid of any repercussions if they were seen to be involved at all."

She had been at Rugby Park when the Hamilton game was called off after protesters stormed the pitch, and knew the potential for escalation.

On August 11, the protesters believed they had come to an agreement with police around where they could march, Ms Holloway said.

But police stopped them and would not allow them to go any further.

He was used to seeing people such as veteran activist John Minto at demonstrations. But here there was a huge variety of protesters, from "Joe Bloggs people like your mother and father", to "hippie-type students".

Words, rather than stones or bottles, were hurled at the police this time.

"There was a wee bit of name-calling," Mr Grindell said.

"It was worse for the Maori policemen. The young Maori cops were getting called traitors. They particularly took a lot of stick."

Some marchers placed olive branches on the officers’ batons.

After a brief standoff, protesters returned to the Southern Cross Hotel where the Springboks had been staying.

"There was a group of people protesting outside there, and I remember there were quite a few people quite angry because we kept what we had agreed, that agreement had not been observed by all parties, so it got quite loud and noisy," Ms Holloway said.

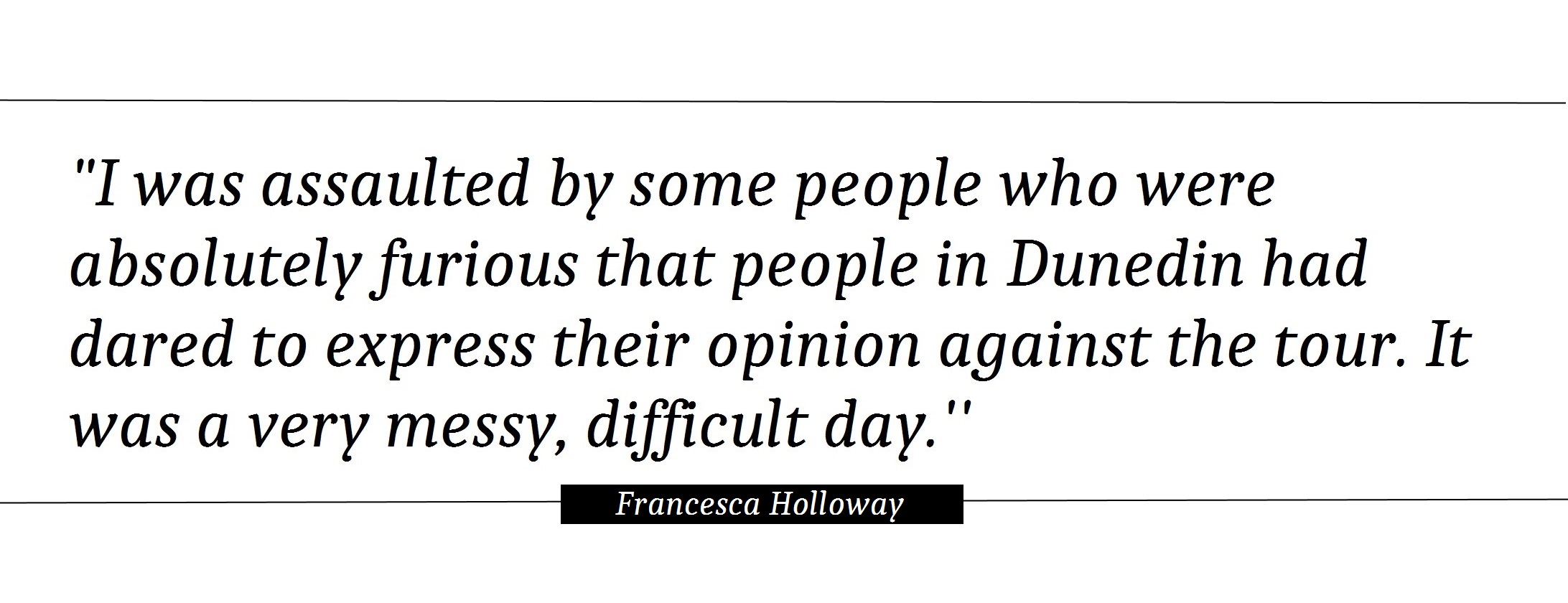

"Walking away from that later on, I was assaulted by some people who were absolutely furious that people in Dunedin had dared to express their opinion against the tour. It was a very messy, difficult day. It was very intense, with a lot of people trying to stay calm while dealing with a lot of emotion and adrenaline surges."

The assault case later went to court, but she said it came with the territory back then.

"While I was living in Dunedin in the lead-up to events I received telephoned death threats and all sorts of threats being made which were fairly unsettling."

It wasn’t all bad. Now 64, she remembered the feelings of solidarity, of standing up for something important.

She also began a relationship with a young man, writer and columnist Chris Trotter. Forty years later, the pair are still married.

"When our daughter was at primary school, her social studies class was studying the tour. I don’t think her teacher had counted on the amount of material we provided."

She believed the relationship between protesters and police, so fractured in other parts of the country, was quite constructive in the South.

It did deteriorate on the final day of the tour, where protesters cut television transmission cables and blocked the intersection of London and George Sts.

There were so many arrests, the male detainees had to be housed in a tent outside the police station.

On the field, Otago ended up narrowly losing to the visitors, 17-13.

Everything changes

For Const Grindell and Blue Squad, the first real taste of the chaos that was to come was in Christchurch during the first test match.

"Christchurch was a real eye-opener. I’ll never forget that day.

"I’ve never been in a war zone but it felt like it."

He and the other officers had to block a large group of demonstrators as they neared Lancaster Park.

Coal and stones were thrown at police, and protesters defied orders to stop their march.

That was the first time Blue Squad used batons against protesters, Mr Grindell said.

He described it as several straight pokes in the midsection — "you’re not hitting them over the head or anything". But he didn’t feel good about it.

"When you saw a lot of those people in that front line, a lot of them weren’t hardened radi cals.

"That was the first time you started to think ‘shit, is this worth it?’."

The clashes continued around the country, culminating in the Day of Rage in Auckland during the third and final test.

During the violence that erupted around Eden Park, Mr Grindell recalled another Dunedin officer being knocked unconscious by a flying bottle.

"There was a lot of force used against protesters, a lot.

"I don’t think any of it was unreasonable at the time, but you start to think back, shit, is a game of rugby worth this."

One of the tour’s enduring legacies was a change in attitude towards police, hebelieved.

A lot of people who had thought highly of police no longer did.

"You have to have public approval to be able to police properly.

"We noticed it. It took several years for us to build up trust with a lot of the public after that."

Looking back, Mr Hudson doesn’t regret playing the game.

"They always say ‘sport and politics shouldn’t be mixed’.

Well it always has and always will be.

"The way that I saw it was the sport could unify a lot of things and unify cultures, maybe."

Comments

And now we live in a country where the Government is hell-bent on bringing in separatism.

We were part of a church group camping with our families at Castle Hill, on the road from Christchurch to the West Coast. We threw snowballs at the Springboks bus as it passed on its way to Greymouth! 😊