And today, Hungary's sunniest town is basking in the glow of its title as a European Capital of Culture for 2010.

But like the rocky path from Roman settlement to humming university town, the road to Pecs' spruced-up state has been long and bumpy.

With the cultural capital designation - which the town shares this year with Istanbul and Germany's Ruhr Valley - came the promise of European Union funds for renovating city parks, building a concert hall, library and arts centre and staging concerts, exhibitions and festivals around Pecs and in neighbouring towns.

But just as funders were opening their wallets to pay for those ambitious projects, the international banking crisis exploded.

And because Hungary is not yet on the euro (it still uses the forint), shaky currency conversion rates and quickly vanishing loan sources forced the organisers to scramble for funds, delaying construction.

That's why, even on a June trip to Pecs (rhymes with "h"), I found myself stepping around chopped-up footpaths, skirting fenced-in construction sites and muddying my shoes on rutted streets.

Still, Pecs didn't fail to charm.

Located in southwest Hungary, it's known as the "Mediterranean City", which might seem like a joke given that Hungary is a landlocked country.

But something about Pecs' position between the gentle Matra and Villany hills means that it gets an average of 200 days of sunshine a year.

Plus, many of its Hapsburg-era buildings, including the post office and the town hall, are painted in cheerful, candy-colour pastels.

Wandering the winding streets, you can imagine the sea just around the next corner.

The first stop on any walking tour of town is the Gazi Kasim Pasha Mosque, now the Inner City Parish Church.

It's generally known as the Mosque Church, however, having first been built as a church, then destroyed and remade as a mosque in the 16th century by the occupying Turks, then remade again into a church after the Turks' expulsion at the end of the 17th century.

It was expanded and redeveloped several times over the ensuing centuries, but Arabic inscriptions from the Koran are still visible in portions of it today.

A prayer apse faces Mecca, and there are distinctive Islamic geometric decorations and arches below the central domed roof.

When the Turks invaded Hungary to expand the Ottoman Empire in the mid-1500s, they found Pecs so inviting that they took over the thriving medieval town, driving locals outside the city walls.

Some of those walls still ring the inner city, offering visual interest and a challenging climb for visitors seeking views of Pecs and the hilly countryside beyond.

Go up the barbican tower at the corner of Klimo Gyorgy and Esze Tamas streets for the best vistas.

Pecs' proximity to the Balkans and Italy - the city calls itself a gateway to the Balkans - is one of its major draws.

Around town, the most obvious evidence of these neighbours is found in the restaurants: terrific brick-oven pizza at Az Elefanthoz, luscious pastas at Crystal, and Serbo-Croatian restaurant Afium's lovely "hatted" bean soup, which comes in a ceramic bowl covered with a baked bread top.

But long before there were separate countries whose citizens now make Pecs their home, the Romans ruled the city, and what they left behind is stunning: numerous tombs of the wealthy Christian citizens of Pecs from the 3rd and 4th centuries.

Hungary officially became a Christian nation (thanks to sainted King Istvan) in the year 1000, but nearly eight centuries before that there were Christians in Pecs.

In the Cella Septichora Visitors Centre, a multi-storey labyrinth leads to vaulted stone tombs from around AD390, remnants of the city walls, and viewing platforms and windows into the grave sites, with their frescoes depicting saints and Bible scenes, plus still-vivid geometric and floral patterns.

Inside the nearby Early Christian Mausoleum is an even older site, an excavated chapel from around 275.

All of the early Christian spots are now designated Unesco World Heritage sites.

The early Christian sites are near the remains of the medieval city walls.

Just up the hill from them is St Peter's Cathedral, whose walls and ceiling are covered in stunning late-19th-century paintings.

King Istvan declared Pecs a bishopric in 1009, but the church that stood on the cathedral's site was destroyed by a fire in 1064, and the basilica now there took another two centuries to build.

The Turks used the building as a mosque and its crypt as an armoury.

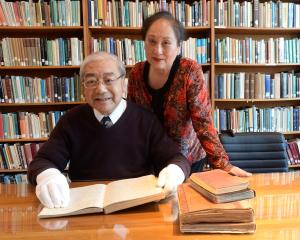

On one visit to the cathedral, I found most of the north wall obscured by scaffolding, part of an ongoing restoration project.

At the top of the wooden platform, I saw an elderly man gingerly retouching saints' portraits and Bible scenes close to the ceiling.

Watching the restorers scraping and plastering St Peter's, I realised something: Culture doesn't mean a thing if it isn't tended.

Maybe that's what all that mud and construction means; maybe that's what the European Capital of Culture designation stands for in the end: that preserving the past to bring meaning to the future takes a lot of work, money, time and patience.

And to witness that transformation in progress is certainly worth a side trip from Budapest.

After two millennia - and a couple of years of renovation - Pecs is finally ready for the spotlight.