For decades, Saudi Arabia has been synonymous with oil and wealth.

From 1985 to 2014, petrol in the oil-rich Arabian kingdom cost 28c a litre, there was no personal income tax and the government books were constantly in the black — oily pitch-black. It was a land of bounty literally built on an amazing energy resource.

But that has changed. Five years ago there was a global oil price slump. Since then, the Saudi government’s books have mostly been in the red, unemployment is 13% and Saudis are struggling to come to terms with the fast-approaching spectre of life after oil.

On the other side of the globe, oil has, for decades, been the single biggest component of New Zealand’s energy mix, followed by gas, geothermal, hydro and coal. And for all those years, most of our oil has come from Middle East states, including Saudi Arabia.

But that is about to change, as New Zealand increasingly taps into an abundant energy source of its own. Wind.

Already 40% of this country’s primary energy needs and 80% of our electricity comes from renewable sources. But as the Government responds to climate change by decarbonising the economy, as the demand for electricity surges when fossil fuels are priced off the market and as the nation transitions to 100% renewable electricity generation by 2035, there will need to be a massive increase in renewable, carbon-free energy generation. The answer is literally blowing in the wind.

It is a markedly different future. A renewable, hopefully sustainable, future. And it has already begun.

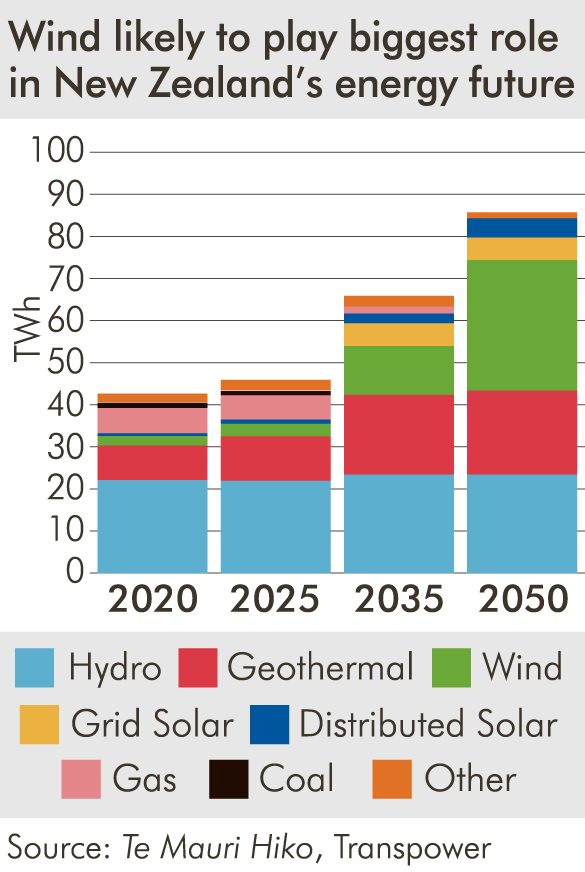

The news that wind will play the leading role in New Zealand’s energy future was put up in lights by Transpower white paper Te Mauri Hiko, released last year. The report stated that electricity demand was likely to more than double, to about 90TWh (terawatt hours) per year, by 2050. By then, electricity will supply more than 60% of our total energy needs, having replaced all coal-fired industry and electricity generation as well as 40% of gas-fuelled industry. Electricity will power most aspects of our lives, including 85% of personal vehicles.

Wind and sun will generate all that extra power, with a little help from geothermal and tide energy, Transpower says. Most of the solar energy will be installed by households and businesses. Wind will be the energy source the big generators invest in most heavily.

To meet the demand, 4.5 average-sized wind farms, of about 60 turbines each, would have to be built every year, starting in 2025.

Transpower’s report excited and galvanised industry players and academics in the energy sector. As did the Productivity Commission’s Low Emissions Economy report, of last year, which also identified wind’s importance.

The crux of the first ‘‘why’’ is the urgent need to ‘‘decarbonise the economy’’. That’s the new way of saying, ‘‘stop using fossil fuels’’.

At present, fossil fuels provide 65% of New Zealand’s total energy needs. Oil makes up 44% and gas 15%. Coal, on 6%, is as big a player as wind in generating energy.

Those carbon-emitting fossil fuels are threatening to tip the planet into potentially catastrophic climate change.

In response, politicians have finally got the ball rolling on a wholesale shift to a low-carbon future.

‘‘This Government sees an important role for wind in decarbonising our economy, bringing down power prices for consumers and creating new, high-paying jobs,’’ Energy Minister Megan Woods says.

‘‘We have to get the regulatory settings right to encourage the transition to [this] more affordable and renewable energy.’’

Why wind?

Gaskell is the enthusiastic chief executive of the New Zealand Wind Energy Association.

The Roaring Forties is a band of strong westerly wind that whips around the ankles of the globe. The South Island and the lower North Island of New Zealand sit bang in the path of the Roaring Forties.

It means we have an ‘‘amazing opportunity’’ to make the most of ‘‘this incredible natural resource’’, Gaskell says.

Internationally, a wind turbine that operates 25% of the time is considered to be offering a decent return. New Zealand has plenty of locations where the capacity is closer to double that.

Way back in 1996, during its first six months of operation, the Hau Nui wind farm in the Wairarapa broke world electricity production records for its type of turbine, Gaskell says with pride.

‘‘There is no doubt wind is a hugely important part of New Zealand’s energy future,’’ he says.

‘‘Wind is internationally regarded as the lowest-cost form of renewable generation.

So, there it is. Wind is plentiful, renewable and cheap.

Reorienting a country’s energy supply is comparable to spinning a large wind turbine; one whose blades turn an arc that can encircle an entire commercial jet airliner. It can take more than a puff to get it moving. But the momentum in New Zealand’s wind farm industry is already building.

The country has 19 wind farms, generating 690MW. That’s roughly enough to supply Wellington, or the Otago/ Southland region (excluding Tiwai Point aluminium smelter), or 300,000 homes.

A further 2500MW of wind generation is already consented, ranging from the 45MW Titiokura wind farm in Hawke’s Bay to the 286 turbine, 858MW Castle Hill wind farm in the Wairarapa. The largest proposed turbines, 160m tall, are consented for the Puketoi wind farm, also in the Wairarapa.

‘‘This year is looking exciting,’’ Gaskell enthuses.

Three wind farm builds have been announced in recent months, he says. A 31 turbine, 130MW wind farm is planned for Waverley, in Taranaki; in August, construction begins on the $256 million, 119MW Turitea wind farm in Manawatu; and a $50 million, 16MW wind farm will be built in South Taranaki to produce green hydrogen.

Below the Waitaki River, there are five wind farms: at White Hill (29 turbines, 58MW), Southland; Flat Hill (eight turbines, 6.8MW), Bluff; Mt Stuart (nine turbines, 7.65MW), Clutha; Mahinerangi (12 turbines, 36MW), Clutha; and Horseshoe Bend (three turbines, 2.25MW), Central Otago. Sites are being investigated at Slopedown, in Southland, and Mt Stalker, North Otago. A site at Kaiwera Downs, Gore District, has been consented for an 83-turbine 240MW wind farm. Mahinerangi, west of Dunedin, has consents to expand from 12 turbines to 100, bringing its capacity up to 200MW.

Steve Symons, Tilt’s chief financial officer, says Kaiwera Downs and stage 2 of Mahinerangi ‘‘remain important projects’’ and ‘‘development activities for these sites are continuing’’.

‘‘However, at this stage we are not in a position to comment on their expected construction timelines.’’

Wind power has already helped reduce New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Figures released by Statistics NZ, on Thursday, show that while the country as a whole has not reduced its emissions during the past decade, electricity and gas sector emissions have declined an impressive 41.7% — a result to which wind power has contributed.

The wheels are turning. But that does not mean it will be without challenges.

Such as landscape value concerns.

Near the middle-of-nowhere termination of Black Rock Settlement Rd, which backs on to the Mahinerangi wind farm, Deon Gray is at home having a well-earned lunch break. He has been stock manager on this farm for 15 months.

The wind turbines, more than 6km away, are visible above the row of trees bordering the paddock behind his house.

He does not mind the sight of the turbines and rarely hears them. Wind power is a good way to use a natural energy source to produce electricity, he says.

A few kilometres further away, on Lee Flat Rd, the turbines are still visible in the distance. Di McClimont has lived here with her two teenagers for the past couple of years. She loves the peaceful country setting. She is not concerned by the prospect of more turbines.

In fact, she would welcome the cheaper electricity that the shift to renewable energy promises.

It was a different story a decade ago, when this scattered rural community was split by the announcement of a wind farm. Some, particularly those who stood to gain what is said to be an annual ‘‘impact reimbursement’’ of $15,000 per turbine, wanted the wind farm to go ahead. Others, concerned about the potential visual and noise impact, tried unsuccessfully to stop it.

A farmer, who does not want to be named, says the rifts in the community are only just beginning to heal. He thinks Trustpower would have got a better reception if it had not raised the spectre of 100 turbines suddenly towering over the landscape. He might be accustomed to the turbines now, but does not want any more. He would prefer to see large arrays of solar panels.

The mix of feeling in Mahinerangi is representative of the reception wind farms have received, and will probably receive, throughout the country. More people seem in favour, but opposition will also be deeply felt.

Gaskell says developments in wind turbine technology are giving better results without the turbines having to be positioned on the crest of hills to be viable. But the reality, he says, is that the best results are on the skyline, where the wind speeds are highest.

‘‘There is a landscape impact,’’ he agrees.

‘‘And our view is that the consenting process requires a rigorous assessment of environmental impacts.

‘‘The reality is, if you want renewable electricity, then wind farms are one of the ways of [getting] that.’’

Gaskell believes the consenting process does not give enough weight to the national importance of renewable energy generation.

It is an issue that is also tied to another challenge wind power faces; getting small-scale community wind farms up and running.

Scott Willis is project manager of Blueskin Energy Ltd, which in 2017 failed in the Environment Court to get approval for a wind turbine on Porteous Hill, overlooking Waitati.

He says Blueskin’s plan is ‘‘in abeyance’’ and there are no other active community wind farm projects in New Zealand because ‘‘the regulatory environment is not right for what is normal in other countries, which is community wind’’.

Willis says all wind power generation projects have to jump through the same hoops, no matter the scale of the proposed wind farm. He wants a separate national environment standard established for small-scale wind generation.

A third challenge is largely technical. And its solution offers some exciting possibilities, Murray Sherwin says.

Sherwin is the head of the Productivity Commission, which produced the Low Emissions Economy report for the Government.

He agrees wind is ‘‘a very important part of the future of energy in New Zealand’’.

‘‘Wind has become a lot more economically viable,’’ Sherwin says.

‘‘Prices have dropped, as happened with solar. It’s probably now the go-to for extra capacity.’’

But wind, like solar, has a problem. It is not a steady source of energy, Sherwin says.

Solar panels struggle when the sun does not shine. Wind turbines cannot make electricity when there is no wind.

Admittedly, climate change is expected to bring stronger westerly winds. But New Zealand will still have to rely on hydro and geothermal energy for that steady base. Except in dry years, when hydro will also struggle to meet demand.

Sherwin says one way to compensate would be to ‘‘overbuild wind capacity’’; ensuring there are enough wind farms to cover peak demand even when hydro dams are low.

‘‘But it’s expensive to have plant just sitting there doing nothing.

‘‘So, some are looking at using that surplus capacity to electrolyse hydrogen.’’

When not needed elsewhere, the wind farm electricity could be creating green hydrogen fuel.

‘‘Which might turn out to be highly valuable, especially for heavy transport and maybe, eventually, in cars,’’ Sherwin says.

That idea will be tested at the 16MW $50 million wind farm being built in South Taranaki by Ballance Agri-Nutrients and Hiringa Energy.

The Government is stirring the pot, aware that it will have to help make things happen if the country is to hit its target of 100% renewable electricity by 2035.

It has set up the Interim Climate Change Committee, which will give advice to the yetto-be-formed independent Climate Change Commission on issues including the renewable electricity goal. A report from the interim committee is expected next month.

That has not stopped the Minister of Energy saying she believes two key issues that need to be addressed are consenting barriers and transmission access barriers.

Gaskell and Sherwin agree, adding their own ideas on what the priorities should be.

It is vital New Zealand gets the technology and the price of electricity right, Sherwin says.

‘‘We need very efficient generation and distribution.

‘‘Wind in particular looks like it can do that. But you need the regulatory and market structures right to enable that to occur.

‘‘Yes, I think we are moving in that direction. And people are very alert to the risks and the opportunities.’’

The price put on carbon is critical, Gaskell says.

‘‘The higher the price of carbon, the more you are going to see the transition out of fossil fuel into renewables.

‘‘The opportunity is amazing. We can produce renewable energy at a low cost compared with other countries.’’

We just need to ensure we spin this natural advantage to enhance our economic wellbeing, he says.

New Zealand is unlikely to become the Saudi Arabia of wind, Sherwin says.

‘‘But it could become the New Zealand of wind.’’

If it does that, electricity generated by our abundant, cheap, inexhaustible wind resource could make the land of sheep as envied as the land of sheikhs ever was.

Comments

‘‘The higher the price of carbon, the more you are going to see the transition out of fossil fuel into renewables.“

And is that how they will claim the power is cheaper? Smoke and mirrors!

We need more hydro!

Get the Lower Waitaki scheme out of mouth balls!

We need that Gas off the cost too!

It will get hydrogen systems in place that we must have, because you can’t run every process / service we need on electricity.