Climate change will reduce the income of the global economy by 19% by 2049, according to international scientists - and New Zealand will be among the countries feeling the pinch.

By mid-century the economic damage caused by a hotter planet will amount to $38 trillion every year.

The world economy now is about $100 trillion a year.

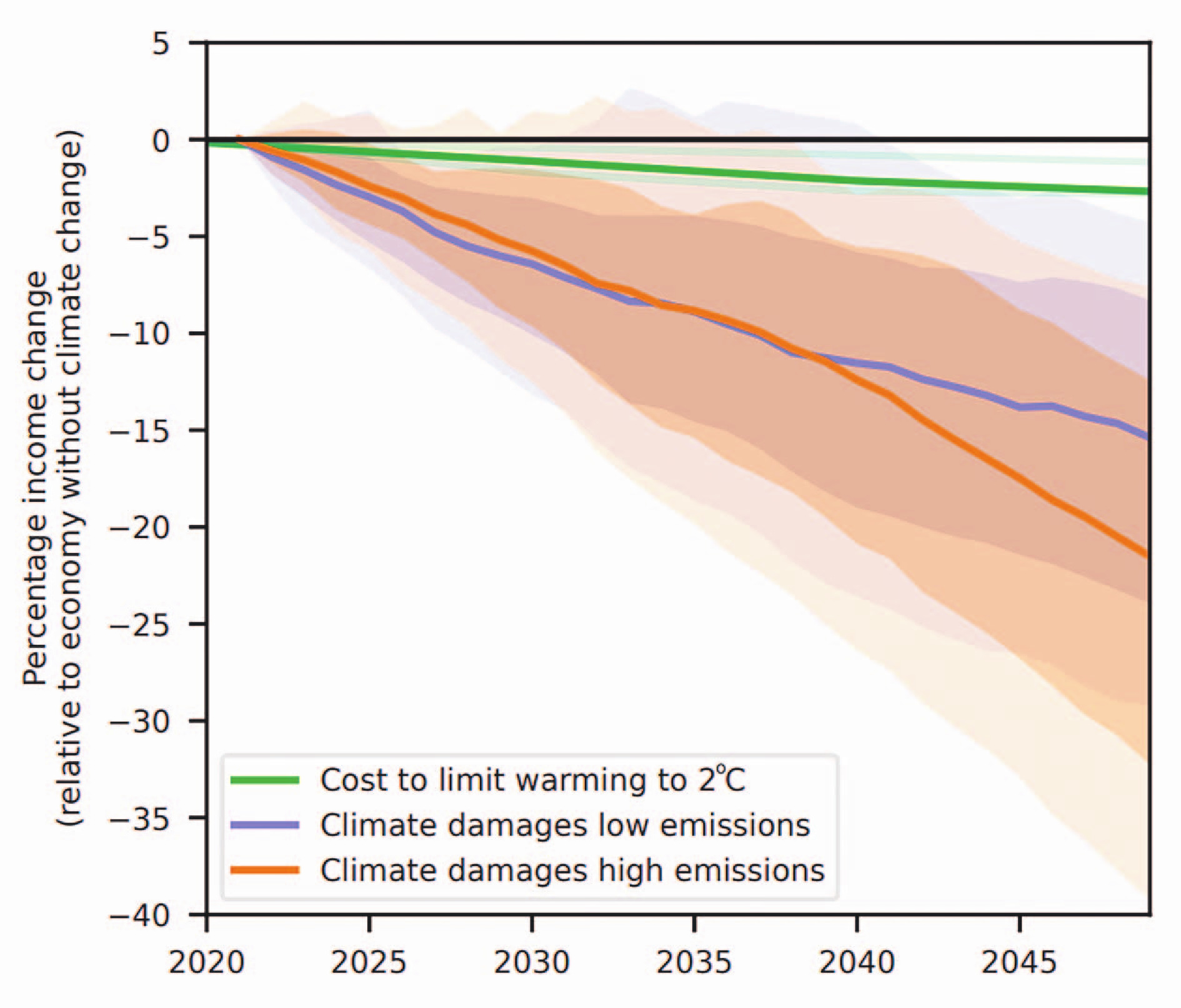

The projected damage is six times the cost of limiting warming to the Paris Agreement targets, the researchers say.

The study team used local temperature and rainfall data from more than 1600 regions around the world and combined it with climate and income data for the past 40 years to model likely outcomes — resulting in more "granular and empirical" results than previously achieved, according to commentators.

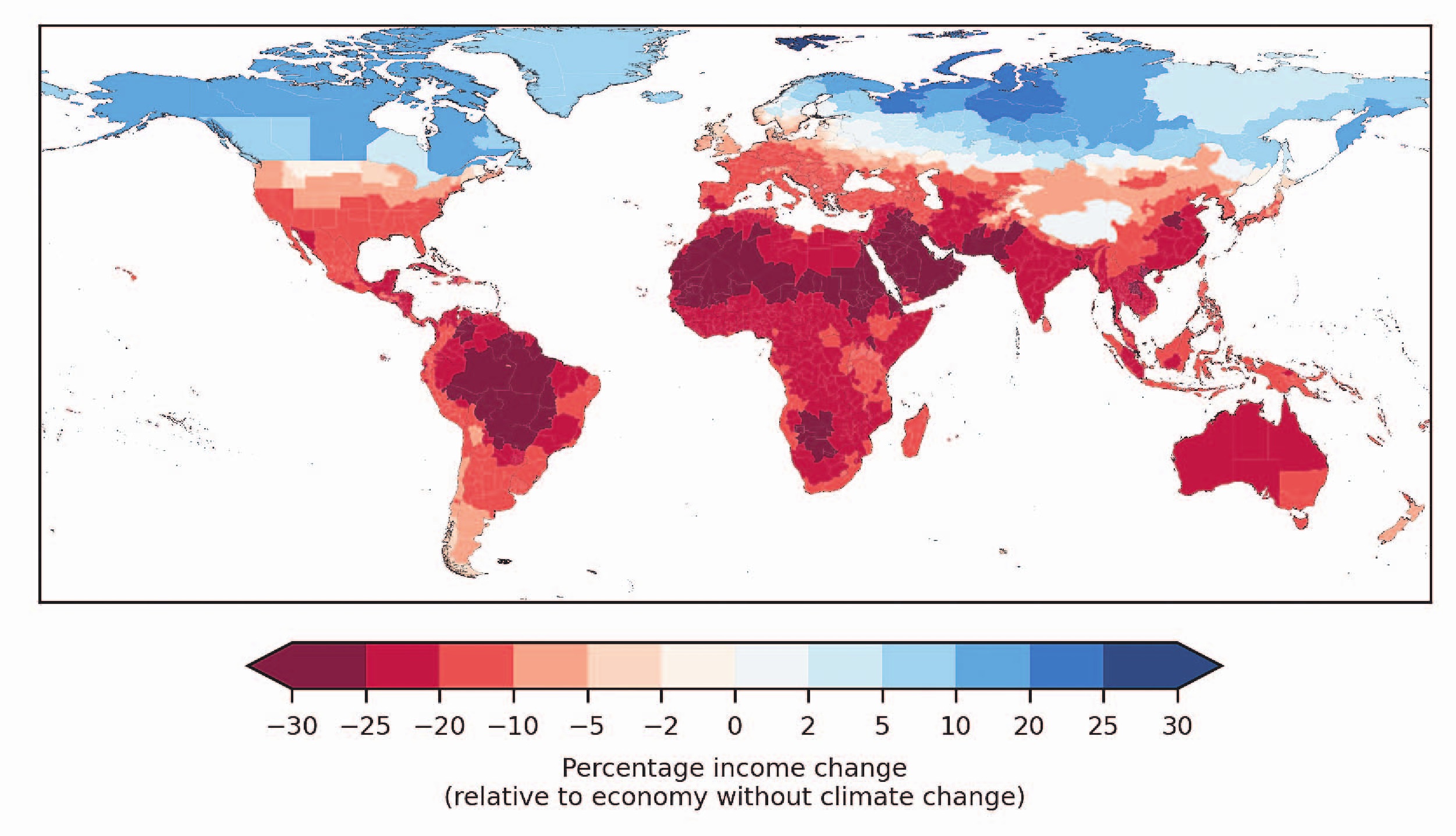

The research shows that New Zealand’s income will be up to 10% lower, Auckland and Northland the regions worst affected.

The study, published in the journal Nature, employs new models that shed further light on the potential consequences of unrestrained carbon emissions, the authors say, and suggest that the impacts will not be felt evenly across the world.

Projections of the economic damage of climate change are crucial to the adaptation and planning procedures of both public and private entities, they say.

The research was led by Dr Leonie Wenz, deputy head of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Potsdam, Germany, and found the damage is already locked in due to previous emissions — the world economy can not now avoid the income reduction of 19% by 2049.

"It’s devastating," Dr Wenz told The Guardian. "I am used to my work not having a nice societal outcome, but I was surprised by how big the damages were. The inequality dimension was really shocking."

By 2050, the study calculated mitigation costs — for example, from phasing out fossils and replacing them with renewable energy — to be $6 trillion dollars, which is less than a sixth of the median damage costs for that year of $38 trillion.

The damages identified are primarily attributed to temperature variation. However, the authors suggest that the consideration of additional climate variables raises estimates by a further 50%.

Countries with the lowest income and lowest historical emissions are predicted to suffer income loss that is 61% greater than the higher-income countries and 40% greater than higher-emission countries, suggesting that further warming will exacerbate the effects of climate injustice.

Worst affected will be countries in already hot regions including Botswana (-25%), Mali (-25%), Iraq (-30%), Qatar (-31%), Pakistan (-26%) and Brazil (-21%).

Commenting on the study, Prof Ilan Noy, Chair in the Economics of Disasters and Climate Change at Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington,

said the authors clearly show that the transition to sustainable energy sources is significantly less costly than the cost we are already "committed" to bearing by our past greenhouse emissions.

"So, we would have been much better off had we not delayed climate action for so long.

"Overall, however, this kind of modelling approach is not suitable to conclude much about the costs of climate change at the local level for us in Aotearoa," Prof Noy said. "This approach does not account for the local peculiarities of our economic activities — in our case, for example, that the Waikato region is much more exposed to changes in heat and rainfall than Auckland because of its different set of economic activities.

"But, the fact we cannot conclude much from this work about the local impact does not detract from the main message, that we should rapidly converge to a net-zero world. After all, the argument for us, and for everyone else around the world, to work toward net zero is not that our actions matter locally, but that it is their global impact that is the reason for the urgency we need to adopt."