The transit, during which Venus can be seen as a small dot against the vast backdrop of the sun, also offers a chance to remember centuries of human endeavour and scientific progress as well as reflect on the event's connection to New Zealand's history.

But first, a little explanation: the transit of Venus occurs when Venus passes directly between the sun and Earth.

The alignment comes in pairs that are eight years apart but separated by more than a century.

The last transit of Venus was in 2004 (and before that, 1882). Come nightfall on Wednesday, the next transit won't be seen until 2117, followed by 2125 then the next pair of 2247 and 2255.

In short, the transit of Venus doesn't happen often, so it's worth celebrating.

"It is often said they are the most rare predictable astronomical event," enthuses Peter Jaquiery, president of the Dunedin Astronomical Society, whose excitement over Wednesday's events spans several strands.

"Possibly, the most exciting aspect is the least obvious - the historical interest.

"There is a huge amount of science history that is tied up in the event. For people such as educators it is a really good springboard for introducing scientific history and facts."

Take Jeremiah Horrocks, "a really interesting character" who made the first known observation of the transit of Venus from his home near Preston, England, on December 4, 1639.

Though Johannes Kepler had predicted transits in 1631 and 1761 - and a near miss in 1639 - Horrocks corrected Kepler's calculation for the orbit of Venus. Realising that transits of Venus would happen in pairs eight years apart, he thus worked out a transit would indeed occur in 1639, at approximately 3pm.

"Horrocks died about a year after witnessing the event," Mr Jaquiery explains. "He'd started observing Venus when he was 16 or 17 and when he was about 20 he decided there were errors in the standard tables of planetary motion.

"In the process of evaluating those errors he realised that Kepler's calculation that said the transit of Venus wouldn't happen in 1639 was wrong.

Horrocks calculated when the transit would happen and discovered that he'd be able to view it, so he passed on the information to several friends and they [also] viewed the transit.

"That's pretty amazing for a guy just using bits of paper and a pencil. What a buzz."

Horrocks' discovery, following centuries of mathematical and scientific evaluation, was strengthened by the work of Isaac Newton later in the 17th century; planetary orbits became better understood following Newton's discovery of the laws of motion and universal gravitation.

All subsequent transits were accurately predicted, which in turn sparked a series of expeditions over centuries aimed at answering a leading question of the day: how big is the solar system?

Astronomer Edmund Halley proposed giving the solar system its scale via measurements of Venus at the next transits in 1761 and 1769.

In an attempt to determine the average sun-Earth distance, or astronomical unit, several nations, including Britain, France, Sweden and Russia, commissioned dozens of expeditions to sites around the globe to measure the 1761 and 1769 transits.

The technique involved observing the difference in the time of either the start or the end of the transit from widely separated points on Earth's surface. The distance between the points on Earth was then used as a baseline to calculate the distance to Venus and the Sun via triangulation.

Though astronomers could calculate each planet's relative distance from the sun in terms of the distance of Earth from the sun, an accurate absolute value of this distance had not been determined. Halley had hoped this quantity could be determined with an uncertainty of 0.2%. However, measurements obtained from those 18th-century transits differed by more than 10%.

These days, with the advantages of technology, notably the equipment aboard interplanetary spacecraft, the best estimate of the astronomical unit is 149,597,870.700km (with an uncertainty of just 3m.)

The transit of Venus is still of great astronomical significance. In 2004, ground and space observatories used the transit to measure the degree of scattered light in their telescopes, the high contrast between the bright sun and dark disc of Venus providing ideal conditions for this work.

"In the last decade transits have become topical as one of the ways to discover planets orbiting other stars," the Royal Society of New Zealand explains on its 2012 Transit of Venus Forum website.

"Hundreds of thousands of stars have been monitored for tiny brightness dips and some 130 exoplanets have been discovered in this way ... Astronomers will use the much clearer signals from the 2012 Transit of Venus to assess the possibilities."

Mr Jaquiery says the transit of Venus was the first example of "big science".

"When we talk about things like the Large Hadron Collider, which costs billions of dollars, well, that's modern-day 'big science'. But sending expeditions across the world to record the transit of Venus, which is what James Cook did (in 1769, in Tahiti) is also `big science'."

Cook, of course, had his sights set on places other than the solar system. Following his Tahitian transit observations in 1769, Cook opened secret orders and went on to search for the "Great Southern Continent", exploring the coast of New Zealand and landing at Uawa (Tolaga Bay) in October that year.

One hundred and five years later, in 1874, France, Germany, Britain and the United States sent observers to various New Zealand locations, including Dunedin, Queenstown, Naseby, Burnham, Auckland, Thames and Wellington, as well as the subantarctic islands.

The year 1882 also witnessed the arrival of a range of scientific groups who, according to reports, enjoyed more favourable skies.

The Royal Society of New Zealand is looking ahead as well as up, linking the transit of Venus with a forum aimed at promoting scientific innovation, establishing better connections between business leaders and investigating sustainable development.

Glenda Lewis, project co-ordinator for the Royal Society's 2012 Transit of Venus Forum, says the subtext of the event could best be construed as, "it's amazing what can result from pure scientific investigation".

"In 2004, we did a big educational campaign. I hadn't realised that because Captain Cook came to observe the transit in 1769 in Tahiti he then discovered New Zealand.

"The stories around those expeditions ... these amazing guys who would sail around the world to observe the transit - then it might be cloudy when they got there. Or they took so long to return that by the time they did get back home their relatives had sold their houses.

"Just as we used the transit to deduce the astronomical unit, now we have got some of the world's best planet hunters who are using pretty much the same methods to detect other planets. We know everything about the universe basically by the amount of light," Ms Lewis says.

"I find it fascinating. In this virtual world, if you really want to be impressed, it's these kind of things."

Mr Jaquiery puts it another way: "Unless you're an astronaut and have got far enough away from Earth to view our planet in the context of the rest of the solar system, it's really hard to tell how the Earth fits into the rest of the system.

"When you observe this little black dot crawling across the face of the sun, you are looking at a planet which is roughly the same size as Earth.

"Because Venus is much closer to us than the sun, it actually looks three times bigger than what it would if it were placed right next to the sun. It is about a 30th of the diameter of the sun. It's actually a way for people to realise just how big the sun is."

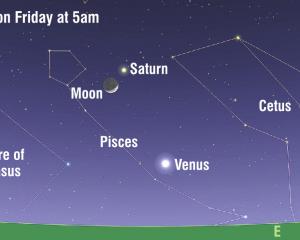

Weather permitting, New Zealanders should be able to view the transit of Venus on Wednesday, June 6.

Venus will begin to "bite" into the edge of the sun at about 10.15am and will have moved completely on to the solar disc 18 minutes later.

The sun will be in the northeast part of the sky, at an elevation above the horizon ranging from 15 degrees in Invercargill to 25 degrees in Whangarei. At transit midpoint, at 1.30pm, the sun will be five degrees higher in the sky, and towards the north. A clear horizon will be needed to see the end of the transit, which will occur just before sunset.

Venus will start to exit the solar disc at 4.25pm and have left it completely by 4.43pm. At this time the sun will be only a degree or two above the northwestern horizon.

The sun is dangerously bright and must be dimmed with an appropriate filter, i.e. one that doesn't just remove most of the visible light. It must also eliminate the invisible ultraviolet and infrared rays which otherwise will burn the eye, Mr Jaquiery says.

"Even with an unaided eye, if you view the sun you are likely to do permanent damage.

"A type of filter commonly used with telescopes reduces the light by 100,000 times. The advantage of using a filter and a telescope is that, obviously, we get magnification with a telescope but we need the filter so we can view the sun."

Viewing sessions with specially adapted telescopes are being organised by local astronomical societies.

"The most basic technology is a solar viewer, which is a rectangular piece of card with a dark plastic filter in it and that reduces the light by about 2000 times. You can then hold that up in front of your eyes and view Venus as it crosses the sun," Mr Jaquiery says.

Members of the Dunedin Astronomical Society will be at the Beverly Begg Observatory to help guide public viewings of the transit, he says.

"If it's raining all day, then that would literally be a wash-out, but if it's cloudy then we'd hope to get gaps in the cloud to view parts of the event.

"And if the weather doesn't play its part, then there are plans to show the event at the observatory regardless - via a Nasa (internet) feed from Motokia, Hawaii."

Though Metservice predicts a risk of showers on Wednesday for both coastal and inland Otago, it should still be possible to view the transit of Venus at various times during the day, with breaks in cloud due to a westerly flow.

A FACT FILE

When: Wednesday, June 6 between 10.15am and 4.43pm.

View it: Through a filter that cuts out most of the visible light and invisible ultraviolet and infrared rays. For a detailed guide on how to make a pinhole projector with which to view the transit of Venus, visit: www.exploratorium.edu/eclipse/how

Where: The Dunedin Astronomical Society will be at the Beverly Begg Observatory, in Dunedin to help guide public viewings of the transit.

Weather: The weather forecast is for rain, but with gaps in the clouds during the day.