Scars on the land tell us Dunedin is earthquake country too, writes Paul Gorman.

It cuts a slice off the southeastern corner of the South Island that’s visible from space.

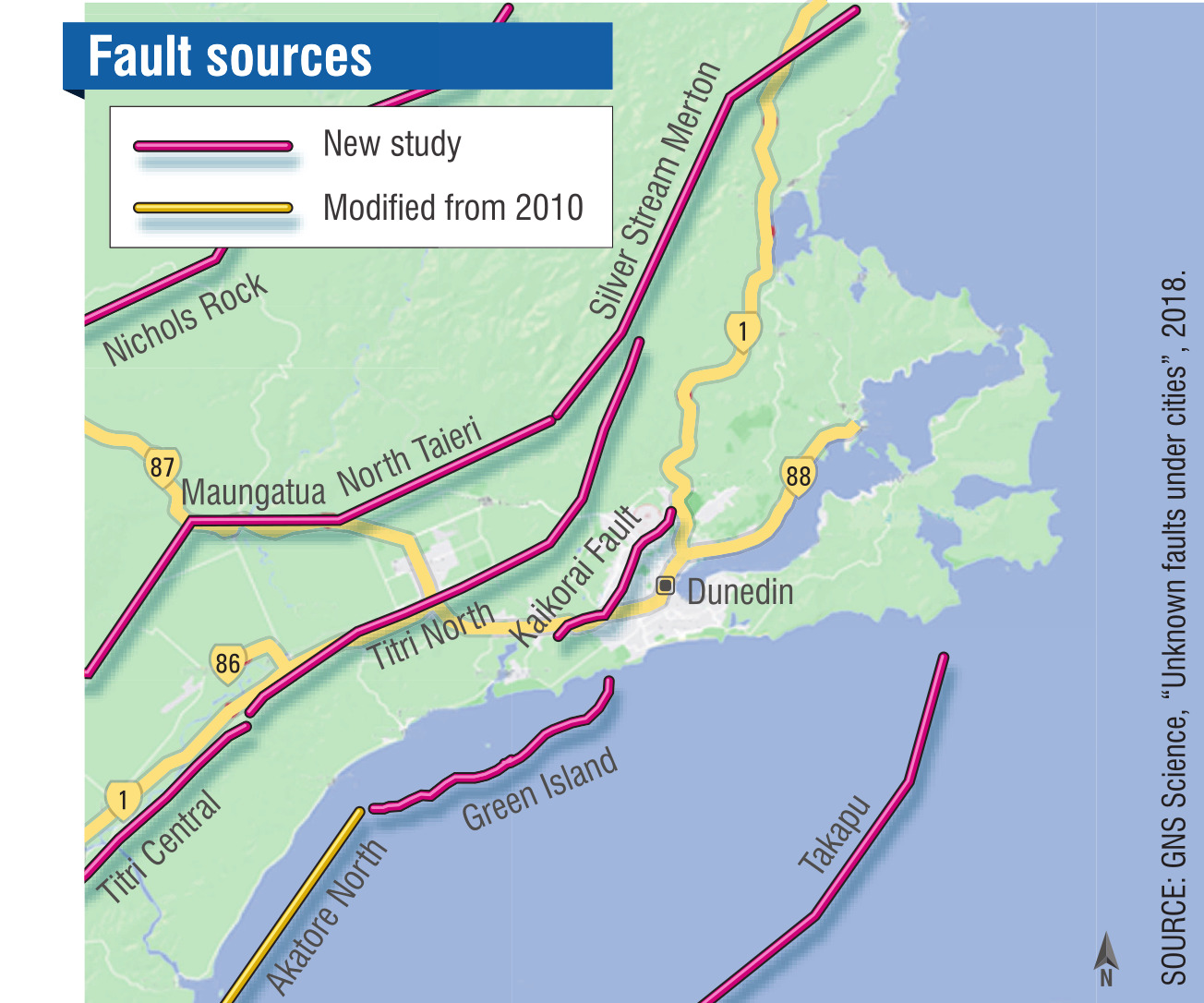

Responsible for at least three magnitude 7.0 earthquakes in the past 10,000 years, the Akatore Fault carves its way across rolling countryside between the settlements of Taieri Mouth and Toko Mouth. But it also runs offshore closer to Dunedin, terminating somewhere around the island of Green Island.

There’s even a subdivision and a newly asphalted road across the scarp where the fault comes onshore through a paddock at Taieri Beach, across the road from the school. Under the terms of its resource consent, buildings must be set back 20m from either side of the fault.

The Akatore is a maverick fault, judging by its recent history. Its ruptures in the Holocene epoch — the past 10,000 years — were irregular, the two most recent large earthquakes occurring about 1000 and 700 years before present — the blink of an eye when it comes to geological time.

That means there was a roughly 9000-year gap and then two damaging quakes within about 300 years. And the last was possibly felt by the earliest Maori settlers in the region.

The University of Otago’s chairman of earthquake science, Prof Mark Stirling, says such recent rupturing makes it an "active fault".

Nobody can know if it might be another 10,000 years before the next big one or whether the fault is much closer to springing into action again.

The three Akatore quakes are estimated to be about magnitude 7.0, which makes them comparable with the September 4, 2010, magnitude 7.1 Darfield quake, that kicked off the recent Canterbury quake sequence.

There’s a difference, though. While the epicentre of that Darfield quake was about 40km from central Christchurch, the Akatore Fault runs as close as about 12km from the centre of Dunedin.

Akatore is not the only local fault Dunedin folk need to bear in mind.The Titri Fault defines the eastern-southeastern edge of the Taieri Plain and has pushed up the hills between the plain and the coast.

GNS Science geologist and geomorphologist David Barrell says the Titri Fault comes within 5km of central Dunedin and has generated major quakes at least twice in the past 38,000 years.

If there are three segments of the Titri Fault, as thought, a future quake could be of magnitude 7.0 if one segment breaks, or as high as magnitude 7.7 in the less likely event of the entire fault rupturing in one go, he says.

Research a couple of years ago has also uncovered a structure now known as the Kaikorai Fault, running roughly along the valley of the same name.

GNS Science earthquake geologist Dr Pilar Villamor says it is not yet clear if the Kaikorai Fault is active, but it is considered "potentially active".

Early estimates are it generates significant quakes from every 30,000 to 1 million years of about magnitude 6.9, although this could be higher, possibly up to magnitude 7.6, if another fault such as the Akatore were to rupture at the same time.

The Hyde Fault is also potentially a concern for Dunedin.

Prof Stirling says this comes within 50km of the city. It last ruptured from 10,000 to 20,000 years ago and is believed to have an average recurrence interval between quakes of about 12,000 years.

It has the ability to create an earthquake of magnitude 7.0 or greater.

Southwest from Taieri Beach, the Akatore Fault goes undercover for about 10km, slicing through the Akatore Creek, mudflats and forests until it reveals itself in all its glory in a puggy paddock crossed by the meandering Big Creek.This otherwise unremarkable field is a geological treasure trove for earthquake experts. Here the fault is obvious as a sharp scarp, about 4m in height, lying right across the path of Big Creek.

The fault actually looks more like a railway embankment, and you’d be forgiven for expecting tunnels at either end where it meets the hills.

"This is one of the best examples of an exposed reverse-fault in New Zealand," Prof Stirling says.

The uplifted side, closest to the sea, is hard schist, but the flat field from which it has risen comprises several metres-thick swampy sediments, underlain by gravel and with Otago’s basement schist further down.

The scarp is the "sum total of the three earthquakes" in the past 10,000 years.

"That is about 4m high. When we dug into this, we could see the progressive displacement of the three earthquakes that have formed this. We estimate [fault rupture] of about 2m per event."

It’s a slippery walk to the fault across the rush-filled paddock, with a few large, steaming cow pats in the bog adding to the excitement.

A four-wheel drive appears and makes easier work of the paddock than us. Out steps Swiss couple Regula and Thomas Fischli, who have owned the 365ha Little Fish on the Roof farm since 2002.

"It was one of the treasures we didn’t know about. A hidden treasure," Thomas says.

Prof Stirling says the Akatore Fault dips at 45deg to 50deg below the ground towards the southeast. Over some millions of years it has created the low range of coastal hills.

"While that uplift has gone on, the Big Creek has managed to keep pace and cut down as the hills have risen up, and that’s called an antecedent gorge.

"When an individual earthquake happens on the Akatore Fault, the Big Creek gets dammed by the fault scarp, so the stream causes a swamp. Eventually, the stream will cut through the scarp and drain the swamp. This has happened repeatedly ... and you have this sequence of swamp sediments, with pieces of wood in them."

When you look at the swampy vegetation around the fault scarp, it is clear the landscape hasn’t fully recovered from that most recent quake, he says.

"We are still seeing the after-effects of that last earthquake."

Otakou kaumatua Edward Ellison (Ngai Tahu and Te Atiawa) believes it is possible the first Maori in coastal Otago may have felt that Akatore Fault quake.

"The earliest people to arrive were the Waitaha, which probably coincides with that event around 700 years ago, thereabouts. Ngai Tahi only arrived 200 years or so ago and Kati Mamoe 100 years before that.

"So we are talking about the very earliest people, and they had the most fabulous creation stories for the South Island.

"Our ancestor, Rakaihautu, is credited with having dug the great lakes with his ko, or digging stick. That’s how they remember the events and paint into the landscape their stories.

"That is a fabulous story about creation, and that prompts me to think there may or may not have been a linkage."

Post-dating that, it was believed Kati Mamoe chief Te Rakitauneke had a pet taniwha.

"On his journeys, he left the taniwha behind, and it went looking for Te Rakitauneke, and on those journeys it is said the taniwha, called Matamata, gouged out the Otago Harbour.

"Also he gouged out the hole where Mosgiel is now and then also, the winding nature of the Taieri River going down through the Taieri Plains is said to be created by this taniwha slithering down the plains looking for its master."

But it’s worth remembering that low level of seismicity is based on only a few hundred years. And it is only low relatively speaking, when compared with more active parts of New Zealand, such as Fiordland, Wellington or the east of the North Island.

Otago Regional Council natural hazard analyst Dr Ben Mackey says a possible major earthquake is just one of many hazards that can affect life and livelihood across the region, as many coastal Otago residents will be aware.

"In particular, ground shaking due to earthquakes is a potential hazard region-wide. It’s important that people living in this environment are aware of possible risks."

GNS Science’s Mr Barrell says the Titri Fault is about 90km long. It starts near Milton and continues to around Wingatui as a surface fault. It then runs northeast as a buried fault below Three Mile Hill and Flagstaff, ending just north of Swampy Summit.

"Data from trenching and dating investigations near Milton indicate that the Titri Fault has ruptured at least twice in the past approximately 38,000 years. The earlier rupture occurred sometime from 38,000 to 28,000 years ago, followed by another one sometime before about 18,000 years ago."

Scientists have calculated a range of approximate recurrence intervals for Titri Fault quakes from about 5000 to more than 40,000 years.

"We are still analysing data from the Titri investigations work and, by the end of this year, there may be further minor refinements to our assessment of Titri Fault behaviour — some approximate values becoming ranges within narrow uncertainties — but the main conclusions are expected to stand," he says.

Dr Villamor says there are still "large uncertainties" about the Kaikorai Fault.

"From the evidence gathered, we’ve yet to confidently establish whether it is dormant, inactive, or active.

"With the limited information we have, we’ve estimated its rupture intervals range between 30,000 and 1 million years, [but] determining rupture intervals and rupture size in low seismicity regions such as Dunedin and coastal Otago is scientifically challenging.

"There is a suggestion that local faults are connected and involve ‘teamwork’ to relieve stresses associated with plate tectonic motion, with one fault being active for a period then switching off while activity is passed to another fault for a period."

While Dunedin is a low seismic-hazard area, it is not hazard-free, she says.

"Even though earthquakes are rare in this region, it makes sense to be prepared. The aim of our fault studies is to try to build a fuller picture of Dunedin’s earthquake hazards, because we want the best possible information available to decision-makers."

A three-year study to build a fuller picture of Dunedin’s quake hazards used topographic and geological maps, geophysical information and seismic imaging to detect deformation just below the surface and measurements of gravity across the region.

"Data from a temporary deployment of 18 seismographs across the Kaikorai Fault did not detect any micro-earthquakes.

"Measurements of current deformation with land-based geodetic stations and from satellite images hardly detected movement across the city — we could only measure 1mm a year of contraction between GPS stations at the University of Otago and a GPS station in Alexandra.

"The low geodetic rates confirm low fault-activity rates in the region. [But] in our study, we are always mindful that the ‘absence of evidence’ is not ‘evidence of absence’.

"We believe it is safer to treat faults as ‘guilty until proven innocent’ in terms of being a potential hazard," Dr Villamor says.

Dunedin may sit in a low seismic-hazard area, but there’s a sense of troublemakers gathering all around.

Drawing on a career of experience here and overseas, Prof Stirling offers a scenario that gives pause for thought.

"Seeing Canterbury and Kaikoura and some international earthquakes, I would say, yes, if an Akatore Fault earthquake happened and it ruptured its full length, there would be very significant damage to heritage buildings in Dunedin."

The question is, is Dunedin prepared for the day it happens?

Further information about the Dunedin faults can be found in this GNS report: https://tinyurl.com/y5urabto. This series of features and online content was made possible by a grant from the Aotearoa-New Zealand Science Journalism Fund and EQC. Online content produced and edited by ODT videographer Rudy Adrian.