On the first page of news in the Otago Daily Times (ODT), on August 13, 1906, shoehorned between "The South African troubles" and "Supreme Court in chambers", vying for attention with advertisements for La Vida corsets at 4 guineas and Hudson’s Eumenthol Jujubes "for throat, voice and lungs", is an article headlined "Presentation at Mount Cargill".

It is an account of the celebration of Mount Cargill stalwart Alexander Graham’s many years’ faithful service to his community. Receiving almost as much praise in the report, however, is the evening’s MC, Jean Souquet, who is described as having done "splendid work".

"Indeed, it would be impossible to write too highly of what that gentleman accomplished," the reporter states.

"Songs, speeches, recitations, story, supper, cheers ... ending with ‘God save the King’, brought to a close one of the happiest reunions ever held at Mount Cargill."

No hint is given as to why Jean Souquet can perform his duties so ably. No suggestion he was born in poverty, in France; developed an international career as a bear tamer and circus showman; and now lived on Mt Cargill with his wife, his rapidly growing family and a monkey.

Repopulating the history of Mount Cargill with a French bear tamer and his household has been a collaborative effort.

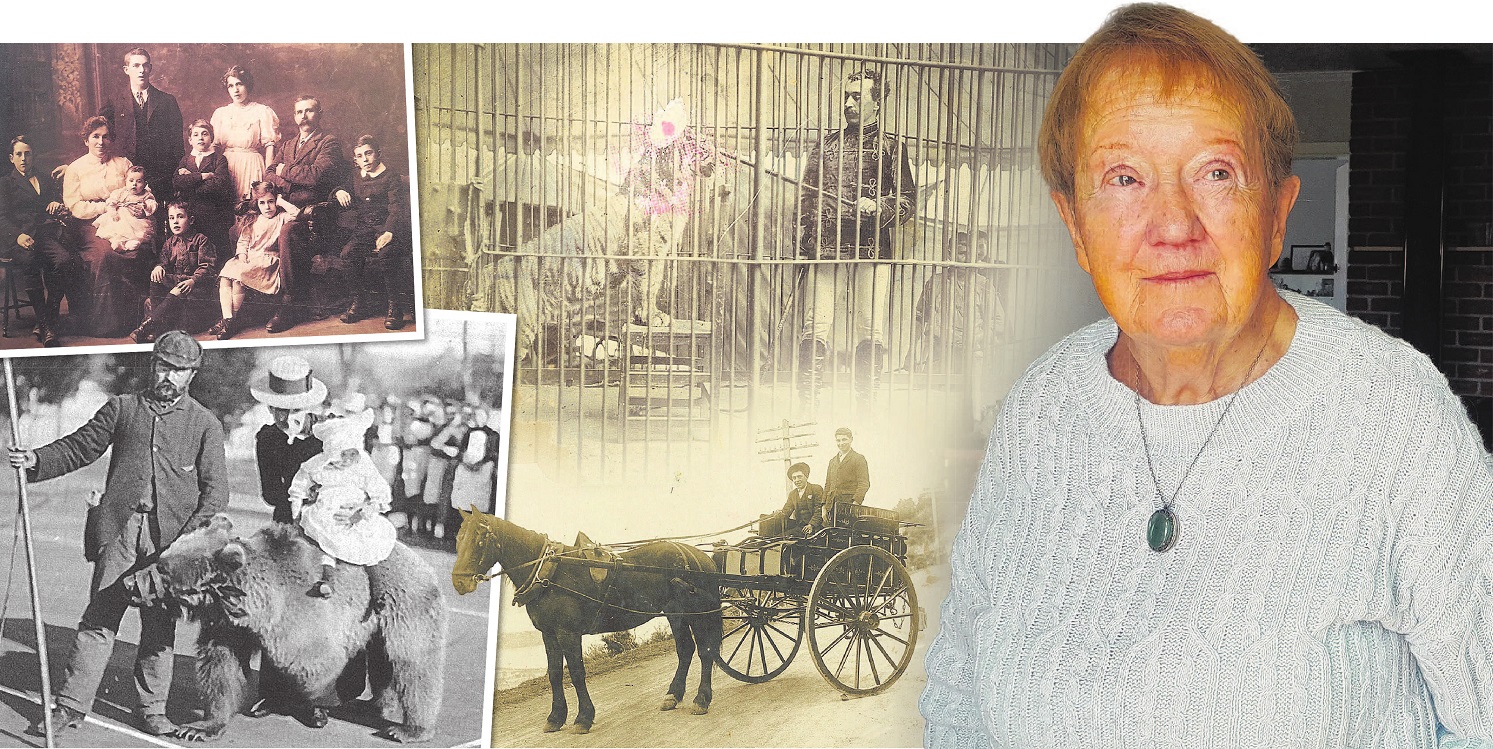

The Souquet’s granddaughter, Edith Schwass (nee Souquet), 84, of Karitane, knows some of the story. Her husband Terry has nudged her to tell what she knows.

"I pushed ... because it’s part of history and when it’s gone you can’t get it back," Terry says with feeling.

Canadian amateur historian Francoise Lewis has documented the big picture, as well as details about the Souquets, in her self-published, 2010 book Montreurs d’Ours en Australie et en Nouvelle Zeland (Bear handlers in Australia and New Zealand).

And then there has been Papers Past — that vast and precious, keyword-searchable, National Library of New Zealand, online archive of newspapers, magazines, journals and letters.

Jean Souquet was born on October 28, 1861, in Erce, a small village hidden in a wooded valley of the Pyrenean mountain chain, in southwest France. He is born the year Tsar Alexander II, of Russia, frees the empire’s serfs; Abraham Lincoln is inaugurated as 16th President of the United States; the Meiji Restoration ends the rule of shoguns in Japan; and the Otago gold rush begins.

About the time Jean is born, the men of Erce begin leaving their impoverished, mountainous home every spring. They leave with bears they have caught and trained, to tour and perform in England and America; returning each winter, or not at all.

By the time Jean is 17 years old, it is a well-worn path. He too gets his performer’s identity card and, with friend Raymond Pujol, leaves with bears in tow. It is not clear where the pair go, but Lewis says Jean is next spotted in official records when he returns to Erce, in 1881, for compulsory military service that includes three years in Tunisia, North Africa.

In 1889, Souquet, now 28, leaves again with bears and his showman’s ticket. He travels through England and Scotland, then boards a ship for Quebec, Canada.

Jean surfaces again in January, 1892. For the next 18 months, advertisements for the "Souquet Brothers" — Jean and his boyhood friend Jean Rogalle — and their performing bears appear in newspapers throughout Hawaii, Australia and the North Island of New Zealand.

An advertisement in Honolulu’s Daily Bulletin, on January 2, 1892, touts, "Performing Bears! ... Dancing and tricks by two bears ... Wrestling match between the bears ... Bears will drink out of glasses to the good health of the people ... Souquet Bros. Champion animal trainers."

In July, 1893, Jean returns to France. When he turns up in Australia six months later, he is accompanied by his new bride, Anna, also of Erce, half-sister of his co-performer.

The Souquet Brothers’ Circus is now travelling regularly between Australia and New Zealand. The Souquet’s first child, Antoinette, is born in 1894. That December, newspaper advertisements place the family in Blenheim and Nelson.

The December 8 edition of the Marlborough Express reports the Souquets have a collection of bears from California and the Pyrenees including a 300lb grizzly and a 250lb bear named Cannelle.

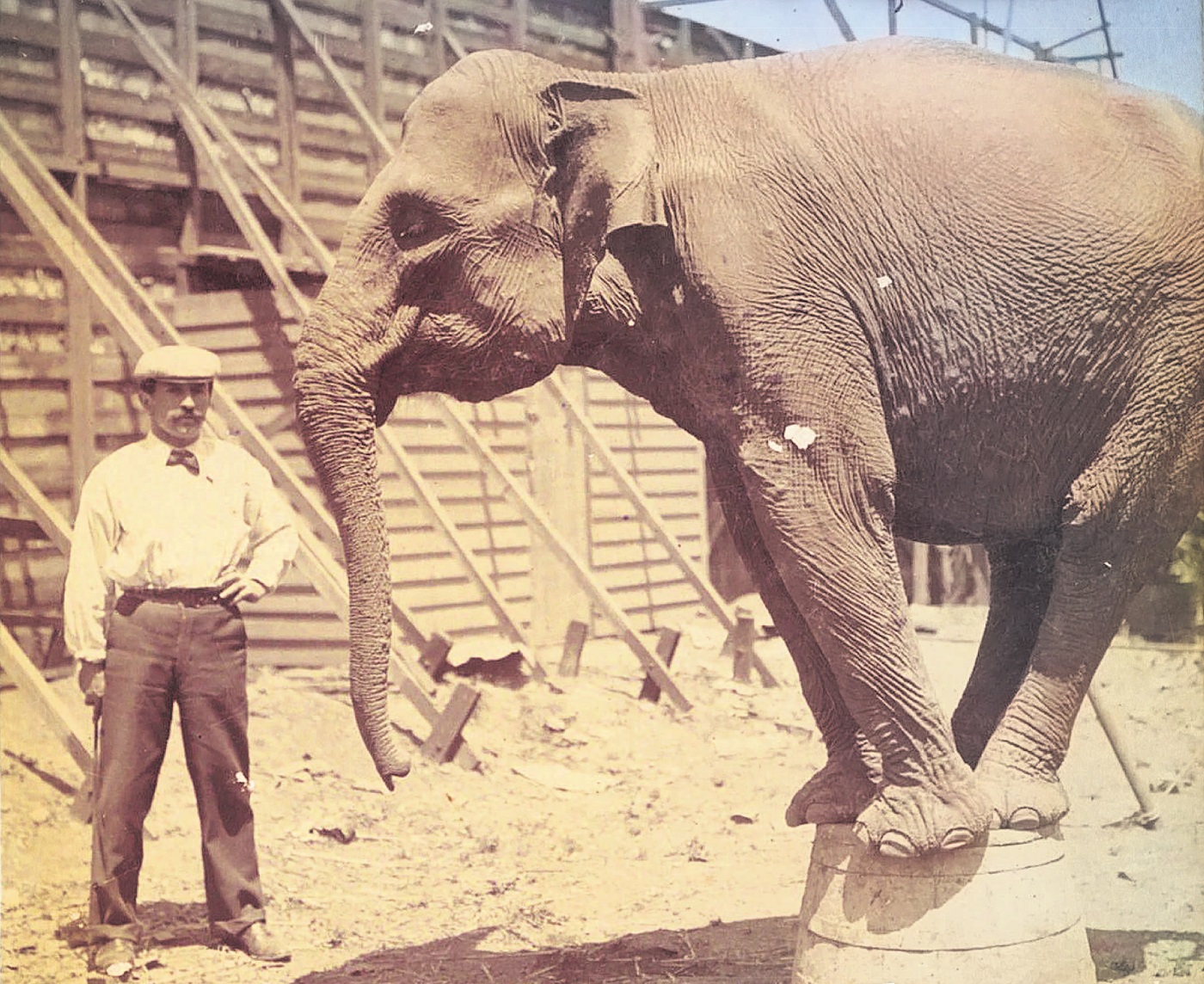

"The bears shoot their guns, dance, wrestle, do various tricks and are ridden by monkeys. During the show we can see the only man in the world who sticks his head into the mouth of a bear."

In February and March, 1895, they are staging shows on the West Coast; in April, they are in Christchurch; May, in Wellington; and August, Sydney, Australia.

Travelling and performing continues. In 1896, a son, August, is born. Two years later, a third child is stillborn.

In 1899, the Souquets arrive in Dunedin.

"Souquet Bros’ Circus and Performing Zoologia was opened on the Harbour Board Reserve, near the site of the New Zealand and South Seas Exhibition, on Saturday night," the ODT reported on May 22, 1899.

"Everyone seemed thoroughly pleased with the performance from beginning to end. The great feature of the show was the excellently trained animals, which included performing bears, dogs, horses, a monkey and a calf ..."

Another son, Louis, is born at the turn of the century. His arrival seems to spark a change.

By September, Souquet Bros’ Circus has disbanded and the couple are with Wirth Bros’ Circus. That circus already has a bear handler, so Jean joins as a tiger tamer. Eight months later, the Souquets abruptly leave after repeated inaction by the circus owner over several attacks on Jean by a tiger in the troupe. Within days, during an afternoon show, the circus owner is attacked and seriously wounded by the tiger.

Jean goes back to bear taming, but only for a month.

According to Edith, her grandparents then move to Motueka.

Her bear tamer grandfather died a dozen years before Edith was born, but her family lived with Jean’s widow Anna for several years during World War 2, when Edith’s father Francois (Frank) was stationed at the gun emplacements on Taiaroa Head, Otago Peninsula.

Reflecting on her grandfather’s showman career, Edith admits to mixed feelings.

"Well, these days it wouldn’t be considered very kosher to be carting and taming bears," she says.

Even in the late-1800s, it appears the practice was controversial in some circles.

In May, 1897, the Sydney Morning Herald reported a Court of Appeal case of cruelty brought against Souquet by the SPCA. The case was dismissed on the basis bears were not domestic animals and so not covered by the relevant Act.

"But ... I think they were pretty good to their animals," Edith adds.

"They had a dog ... Popeye, and they treated him like he was one of the family. And I can remember them all crying when he died."

Despite Anna never gaining a good grasp of English, Edith did hear some stories about her grandmother’s time with the circus.

"She used to sometimes tell people’s fortunes. But she said, ‘It was all lies’," Edith says with a laugh.

When a show was about to begin, Anna would take a bear on a tour of the outside perimeter of the circus tent.

"Because boys would try to sneak in under the edges of the tent without paying."

The move to the top of the South Island, in about 1901, lowers the curtain on Jean’s circus career. While in Motueka, he reimagines himself as a farmer and buys land on the northern outskirts of Dunedin, sight unseen.

"He wasn’t used to cadastral maps, so he bought part of Mt Cargill — he thought it was flat," Edith says, repeating an oft-told family tale.

The Souquets work hard, their family continues to grow and they became integral members of the Mt Cargill and North Dunedin communities.

The original family homestead on Mt Cargill Rd, north of the walking track to the Organ Pipes, is no longer there. Jean built the house and farm buildings himself, paying for the wood by working at a local sawmill, Lewis records.

It is no more than five years after the Souquets’ arrival that the ODT reports so warmly about Jean’s multi-talented performance at Alexander Graham’s retirement soiree — evidence of how thoroughly the family has become part of the community.

During the 12 years to 1916, six more children are born, including a second daughter Maude, Edith’s father Frank and a son with Downs Syndrome, Faustin.

Typical of the time, Faustin, who died aged 26, is not in formal family photos.

The Souquet dairy farm is productive enough to support a milk run in North East Valley.

The October 27, 1915, edition of the Otago Witness, reports Jean and one of his sons being injured when the horse pulling their milk cart bolts, throwing them from the cart.

In later years, the family adds the Mt Cargill Post Office to their income-earning enterprises.

Other family events also make the newspapers: the June, 1914 disappearance of eldest son August (who soon joins the Canterbury Mounted Rifles); the March, 1916 gathering for the same son at Mt Cargill School ahead of his post-recuperation return to war; the December, 1923, dance to welcome back Jean, Anna and daughter Maude after their six month visit to their ancestral home; the May, 1924, report of one of Jean’s paddocks, opposite the Upper Junction School, bearing a "luxuriant crop" of turnips and swedes each weighing up to 13kg; and, the September, 1926, death of second son Louis in a motorcycle accident.

Jean dies suddenly, on April 17, 1928, aged 66, suffering a heart attack after killing a pig.

His obituary in the Otago Witness describes him as "a well-known and respected identity ... [who] established a successful farm ... [and was] the soul of hospitality ... His genial personality and strict integrity won for him a host of friends".

Anna died on November 16, 1950 in her mid-80s.

From one angle, Jean and Anna, in settling on Mt Cargill, appear to have thoroughly discarded their old life of adventure and their French heritage.

There was the monkey — apparently the one animal retained from their performing menagerie — who was still part of the family when Edith’s father Frank was a boy.

"He used to hate that monkey," Edith says.

"Because he had to put clothes on it when there were visitors, and it would poo itself when he got it dressed."

But apart from that living link with the past, the Souquets appear to have encouraged their children to embrace only their identity as practical, hardworking New Zealanders.

The children were not taught to speak French and did not seem to value their parents’ globe-trotting former life.

Two of the brothers, Peter and Raymond, who never married and worked the farm after World War 2, decided to have a bonfire when they shifted out of the family’s second home in about 1950.

"They had all these albums and photos and stuff from the circus, and it was all burnt," Edith recalls.

"My sister Pauline grabbed a handful of old photos out of the fire and took them home.

"That's why we've got any at all."

But Edith has one last story that gives a different perspective, reflecting both Jean Souquet’s showmanship and his enduring pride in his heritage.

"Whenever people visited the family home," Edith says, relaying details from a cousin, "Grandfather insisted that everyone got up and sang the French national anthem, La Marseillaise."